<1> In the 1980s Virago, the groundbreaking feminist publishing house, recovered for a new generation of readers a treasure-trove of forgotten novels by nineteenth and twentieth century women. The distinctive dark green covers of their “Modern Classics” series included three novels by Charlotte M. Yonge. Of these, The Clever Woman of the Family has continued to attract the most attention from literary critics, both from those who take its arresting title as a challenge to their modern sensibilities and from others who observe certain paradoxes in Yonge’s message.(2) It particularly dismays feminists, who interpret Yonge’s story as a rebuff to young women attempting to be independent. None of the critics, however, mention that the story was serialized first in The Churchman’s Family Magazine (Vols. 3–5, Jan. 1864 – April 1865) with twelve illustrations by Florence Claxton. Even Clare Simmons in her scholarly edition for Broadview Press makes no reference to its original appearance.(3) There are a number of reasons why an examination of this serialization offers fresh ideas about the themes of the novel and the context in which it was written and illustrated. Firstly, apart from a few of her books aimed specifically at children such as The Lances of Lynwood (1855), none of Yonge’s previous novels had pictures. Illustrated editions of The Heir of Redclyffe (1853), The Daisy Chain (1856) and The Trial (1864) were not published till 1868. These contained a maximum of four pictures whereas, over the months, twelve illustrations complemented the serial of Clever Woman. Such a large number for a major novel of Yonge gives a different perspective on the original reception of this story in the 1860s. When Macmillan published Clever Woman in book-form in 1865, there were no illustrations; the three by Adrian Stokes were not added until the 1880 edition and were images that reflected the fashions and attitudes of the 1880s rather than the 1860s.

<2> Secondly and of more significance, the choice of Florence Claxton as illustrator raises a number of intriguing questions and presents a fascinating new dimension to the central theme of the story, namely what kinds of work were suitable for gentlewomen, since Claxton was a young female artist forging her own path in a predominantly male profession who had already created a stir. Her controversial painting The Choice of Paris: an Idyll exhibited in the Portland Gallery in 1860 was a satirical attack on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and had merited a full-page reproduction in the Illustrated London News together with a detailed analysis.(4) Even more pertinent to this article, her oil-painting Woman’s Work: a Medley, shown in the Institute of Fine Arts in 1861, appeared to be a comment on the overwhelming masculinity of Ford Madox Brown’s Work as well as on the abundant obstacles stacked against women’s participation in gainful employment. Thus, at first glance, Clever Woman when serialized in The Churchman’s Family Magazine was written by a conservative middle-aged Yonge, as a warning of the folly of young women adopting individualist ambitions, but was illustrated by prints made by a progressive “clever woman” in her twenties. An initial hypothesis might assume that the attitudes of Yonge and Claxton would be diametrically opposed on the critical issue of whether and how middle-class women could pursue employment, but I hope to demonstrate how such a supposition is too simplistic. Both Yonge’s and Claxton’s thoughts about women and work were complex and neither of them can be pigeonholed into antagonistic stances.

Charlotte Yonge and the debate about suitable work for gentlewomen

<3> There is little in Yonge’s surviving correspondence to provide details about her negotiations for the serialization of Clever Woman until a comment in a letter to her friend, the writer Frances Peard: “My clever woman, instead of living alone as she intended when you were here, has had a flirtation with three magazines, and is at present engaged to Hogg’s Churchman’s Family Magazine if she can agree to settlements.”(5) This was John Hogg’s recently founded one-shilling monthly, whose full title was The Churchman’s Family Magazine Containing Contributions by the Clergy and Distinguished Literary Men.(6) Hogg hoped it would compete with the success of Good Words and Once a Week by providing a mix of “Instructive and Entertaining” articles about “Social Questions from the Church Point of View,” “Garden Recreations. Ladies’ Parish Work. Natural History,” “Articles on our Bishops and Deans, with Portraits,” “Missionary Effort at Home and Abroad,” as well as “Practical Papers on Benevolent Schemes” and “Stories for the Young by Popular Authors.” Its key recommendations were that it was “Essentially a Family Magazine” and that it was “Richly Illustrated” (London Society, July 1864: advertisement). All these phrases make it sound an eminently suitable location for a serialized story by Yonge and also suggest that the Churchman’s Family Magazine would provide a wide circulation for this novel. This was important as she wanted to address a topic that had been uppermost in her thoughts and those of her friends over the last few years, namely how should young middle-class women fill their days with useful activities? What sort of work, if any, was suitable? How independent should they be? The publication of My Life and What Shall I Do With It? A Question for Young Gentlewomen by an Old Maid (attributed to Miss L. F. March Phillipps in the catalogue of the British Library) seems to have struck a nerve, provoking soul-searching arguments among Yonge’s wide circle of friends, both married and unmarried, about women’s work and how far their focus should stray away from their immediate domestic responsibilities.(7)

<4> Their assumptions about appropriate behavior and domestic compliance had already been shaken by the extraordinary achievements of Florence Nightingale, a woman with whom they could easily identify being of their own age and class and whose family home was nearby in Hampshire. Early in My Life, the author cites the work of the “lady nurses of Scutari and now in King’s College Hospital” as proof of “what ladies can do” (5), and concludes her book with a rallying cry, “Women of wealth, women of talent, women of leisure, what are you doing in God’s name?” (350). We get a further insight into the ripples caused by the publication of My Life in a letter from Yonge to Anne Sturges Bourne in February 1861:

I am going to send your note about My Life to Hursley this evening. I wish you were here to go over it with M A [Mary Anne Dyson]. She is quite bitten with the book, and would in the abstract like making it a mission and sending the workers out on it. Now I would mark the distinction plainer between girls and women, and I think that without orphanhood or love, girlhood practically lasts till 30, and till then most women are better minding their own neighbourhood. I quite believe that a small parish with excellent supervision spreads as much good around it, as the same gentlefolks could do as drops in an ocean, and that Providence settles their missions for them.(8)

<5> Over the next years Yonge moved this private debate into the public sphere by including a long-running correspondence prompted by the issues raised by My Life in her own periodical, the Monthly Packet.(9) In April 1861 she herself weighed into the discussion: “I make no apology for returning to My Life by an Old Maid. This is a subject most closely interesting to us all, and her startling propositions leave us thinking, discussing, corresponding long after we have closed the book” (MP, XXI, 1861: 446). March Phillipps’s “startling propositions” included the idea that young women should look further afield to help the needy of society and not limit themselves to their immediate domestic neighborhood: “that it is the duty of parents to set their grown-up daughters free to occupy themselves in such works of charity as they wish to engage in” (March Phillipps viii). Such recommendations made Yonge and her friends apprehensive. They wrestled with the problem of balancing familial responsibilities with those towards wider society and thus she cautioned against the false attraction of grand missions that ignored problems closer to home:

There is a strong tendency in human nature to prove that we cannot do the work set us, but could do something else. We could work hard if we had a larger parish, or a smaller one, or one more at hand, or a better clergyman, or one less active, or whom we agreed with, or if we could be independent, or could be directed. Each of these I have heard said, and I have known the very people who sighed for sisterhoods unwilling to rise an hour earlier, or give up a quiet morning, or walk a mile in the noonday sun, or encounter mud. Is the Old Maid quite clear of encouraging such, by offering only what is difficult, and to many unattainable? (MP XXI, 1861: 447)

While Yonge would agree with March Phillipps that a day spent “with Mudie’s books, and work, and drawing, and music, and talking, and with parties now and then,” did not provide “a satisfactory healthy Christian life” for young women (Phillipps 33), she was less convinced by the notion of allowing them greater independence to establish charitable projects of their own. On the other hand, as she had shown in her novel Hopes and Fears, or Scenes from the Life of a Spinster (1860), Yonge was determined to keep abreast of the changes in society and she had castigated middle-aged spinsters who remained backward looking in that novel.(10) It was in this context that she began to plot Clever Woman as a story centred around the blunders made by the strong-minded but well-meaning Rachel Curtis.

The Clever Woman of the Family: women and the meaning of “work”

<6> At the start of the book Rachel feels thwarted – “tethered down to the merest mockery of usefulness by conventionalities; … but I am five-and-twenty, and I will no longer be withheld from some path of usefulness! I will judge for myself, and when my mission has declared itself, I will not be withheld from it by any scruple that does not approve itself to my reason and conscience ”(3). She settles on a scheme to establish a small industrial establishment, “in which young girls might … learn handicrafts that might secure their livelihood, in especial, perhaps, wood engraving and printing. It might even be possible, in time, to render it self-supporting, suppose by the publication of a little illustrated periodical” (140). Her partner in this enterprise is Mr. Mauleverer, a man who is a stranger in the neighborhood and turns out to be a fraud and a villain. The outcome is predictable and Rachel’s little school not only fails miserably but leads to the death of Lovedy Kelland, one of the child apprentices (231). By the end of the novel, Rachel’s come-uppance is complete; in Talia Schaffer’s forceful words, “a barrage of medical, emotional, and legal calamities pummel the heroine into speechless, exhausted self-hatred” (Schaffer 92). It particularly irritates modern readers that Yonge completes Rachel’s capitulation to a more acquiescent form of femininity by marrying her to the soldier-hero, Captain Alexander Keith (Alick), and giving her such submissive words as these, “I should have been much better if I had had either father or brother to keep me in order” (367), implying that in future his dominant male presence will prevent any more silliness.

<7> Clever Woman has attracted numerous critical analyses, possibly because of the variety of ways in which it can be read.(11) As so often with Yonge’s writing, she uses the story to scrutinize a range of characters and situations, and it is not clear exactly what is her own position. Her portrayal of other women in the book, such as the sisters Ermine and Alison Williams, demonstrates her understanding of the many circumstances in which women of her class needed to work, sometimes to earn money, and that work can bring contentment. Yonge highlights the ambiguous meanings of the word “work” early in the story when Fanny is shown round her old home and wonders about the changes to the old schoolroom: “‘What have you done to the dear old room – do you not use it still?’ asked Fanny. ‘Yes, I work here,’ said Rachel. Vainly did Lady Temple look for that which women call work” (14). It is clear that Yonge too is dismissive about the kind of needlework “which women call work” as unsatisfactory and not a true occupation. She recognizes that useful work can bring fulfilment, making Alison (now a governess to Fanny’s children), “infinitely happier and brighter since she has had to work” (66). Yonge’s portrayal of Rachel suggests that her defects were as much to do with flaws in her character as with her progressive ideas about the right of women to follow their own devices.

<8> Yonge is critical of anyone, male or female, who adopts a selfish individualistic path. Audrey Fessler interprets Clever Woman as, above all, a critique of patriarchy and the failure of men to take responsibility for their communities. The Tractarian ideal perceived the good society to be one where the interconnectedness of every person in the community was fostered – that a web of relationships and responsibilities should be maintained in parish and neighborhood. By the 1860s Yonge was a woman of professional expertise and income who gave private advice to many would-be women writers and was involved in working for a variety of charitable projects. Nevertheless, she remained deferential both to her mother with whom she lived and to the Rev. John Keble, who had been her spiritual mentor since the 1830s, believing that such respect was compatible with a busy productive life. Towards the end of Clever Woman, we get a glimpse of what Yonge believed to be the root-cause of Rachel’s downfall when she is introduced by the blind Reverend Clare to “an old friend, a lady who had devoted herself to the care of poor girls to be trained as servants, and Rachel had the first real sight of one of the many great and good works set on foot by personal and direct labour” (345). This suggests that Yonge’s central criticism is of Rachel’s airy-fairy handling of her scheme – her half-digested, preconceived notions and lack of imagination, her failure to keep a close eye on what was happening, her lack of a sense of humor, her gullibility and blinkered refusal to listen to advice – but is not condemning outright the notion of useful work for women.

The Churchman’s Family Magazine

<9> For the opening issues of the Churchman’s Family Magazine in 1863 Hogg secured a number of eminent artists such as John Everett Millais, M. J. Lawless and Frederick Sandys to provide illustrations, together with some worthy clerics to cover church-based topics, but there were no significant works of fiction. Indeed a review in the Spectator ruled that, “The leading tale, a serial story entitled ‘The New Curate,’ seems to us especially weak” (7 Feb. 1863: 20). Hogg would perhaps be able to silence such criticism once he had successfully beaten off the competition for a new story by “The Author of The Heir of Redclyffe,” a best-selling writer known for her ability to create realistic characters and who would not introduce any unsavory topic into his family magazine. As it was also running a series entitled “Ladies’ Work in a Country Parish,” the theme of Yonge’s tale was exceptionally appropriate (CFM 1: 95-103, 196-205).(12) The opening words of the first of these give us a window into the conservative views of the periodical: “We remember how, not many years ago, the literature of the day was inundated by the unsolved question of ‘Women’s Vocation,’ ‘Women’s Work,’ or the ‘Rights of Women,’ until the reading public became perfectly sickened with the subject” (1: 95). Readers with such attitudes would have some of their preconceptions challenged by the issues skillfully raised by Yonge. We can surmise that Hogg believed he had made a coup from the position he gave to the new serial: in January 1864 the magazine opened with The Clever Woman of the Family, “Chapter One – In Search of a Mission,” accompanied by a full-page illustration by Florence Claxton.

Florence Claxton

<10> Unfortunately records have not survived to provide evidence of how and why Hogg commissioned Florence Claxton to undertake these particular illustrations. The obvious link is with his brother, James Hogg, founder and editor of the popular and light-hearted periodical London Society in 1862, where the signatures of both Florence and her sister Adelaide were frequently seen on humorous pictures that targeted the fashions and mores of the day. They were the daughters of the artist Marshall Claxton, whose limited success with large-scale historical and biblical oil paintings had prompted him to travel to Australia in 1850 hoping to find a market there for his pictures. Although he gained a few commissions and caused some excitement by staging the colony’s first Art Exhibition, he and his family left Australia after a few years, spent three years in India, stopped off briefly in Ceylon and Egypt and, in the late 1850s, came back home where, sadly, “his contemporaries seem to have thought him no more than a very competent artist of the second rank” (Macmillan). During their travels as teenagers both daughters had developed their own artistic skills, and also perhaps a broad-mindedness and ability to view the society to which they had returned with a certain detachment. With little training, apart from lessons with their father, first Florence and later Adelaide started to make their way in the risky profession of being an artist – a difficult career path for any man but even more so for a middle-class woman. According to their fellow artist, Ellen Clayton, the finances of the family meant that for both daughters, “it was a matter of necessity … to adopt the profession as a means of acquiring an income” (44).

<11> Antonia Losano’s examination of the negative press and “persistent eroticization of the woman painter,” together with the demeaning language used by magazines such as Punch when, for example, discussing the exhibitions mounted by the Society of Female Artists, reveals the deeply-rooted prejudices against which women artists had to battle (48). Her comments have a direct significance to Florence Claxton who had paintings in the Exhibitions of this Society in 1858 and 1859. On both occasions her pictures were singled out for praise in the English Woman’s Journal. Their description of her Scenes from the Life of a Female Artist (now lost) indicates that Claxton’s painting cleverly satirized the obstacles facing ladies hoping to have success in the “Temple of Fame” (EWJ 1: 208). The following year, this same journal is critical of the general standard of paintings exhibited, but made an exception for Claxton’s Life of an Old Bachelor and Life of an Old Maid. She is lauded as “the one female exhibitor who means something, and says what she means … every stroke instinct with thought. … We think they are … the best pictures here, being so good of their kind” (EWJ 3: 55). As one of the signatories to the 1859 petition to the Royal Academy to allow women the same opportunities as men to study, Claxton was establishing herself as a young woman irked by current assumptions about women’s limited artistic abilities. We are given a further insight into the independence of her outlook by her detailed satirical painting The Choice of Paris: an Idyll, exhibited in 1860, in which she attacks leading figures of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. When the Illustrated London News included a full-size print of this together with an explanation, Claxton’s work received wide publicity. In the few years since the family had returned to England, Florence had made a strong start in launching herself as a professional woman artist.

<12> Her painting Woman’s Work: a Medley, exhibited at the Portland Gallery in 1861, provides further proof of Claxton’s critical attitudes. This strange painting has understandably been the subject of much scrutiny. Susan Casteras asserts that, “This most extraordinary image is one of the few to flaunt custom and to question the position of women in English society and the realm of art. It is, moreover, biting and satiric to both sexes” (226). To accompany it, Claxton provided a text from Aesop with the moral, “no one is fair witness in his own cause,” and a long explanatory description. As Deborah Cherry points out, this extensive passage nevertheless leaves much in Claxton’s creation unexplained and puzzling, and the viewer is free to read the painting in a multiplicity of alternative ways (40). Colleen Denney calls the painting a “multi-layered allegorical portrait,” “a biting satire of women’s service to men; in essence, it reveals the state of women’s lives in 1861 and the ways in which their society marginalized them, whether they sought to stay in the domestic realm, or ventured beyond it into the public one” (22, 24). Certainly Claxton’s dissatisfaction appears to be caused as much by the women’s compliance with the conventions of society as with the complacency of the men. The reference in her descriptive explanation to a cleric and lawyer apparently berating a woman – the “upright female figure to the right … persuaded by Divinity, and commanded by Law, to confine her attention to legitimate objects”(13) – can be interpreted as a warning to women to concentrate on philanthropy and “those social and Christian duties of ‘woman’s mission’ which could be accommodated within conventional definitions of respectability” (Cherry 41). If this is so, and if Claxton’s message is that women should defy such advice, then this would suggest that Florence might be inclined to sympathize with Rachel’s desire to strike out on her own. The title of the painting certainly made it peculiarly relevant to the themes of suitable work for women that Yonge would be addressing in Clever Woman.

Women and the production of wood-engraved illustrations

<13> The proliferation of illustrated magazines decorated with woodcuts in the 1860s provided new opportunities for competent artists if they were prepared to turn their hand to this type of work.(14) Catherine Flood has highlighted how drawing on wood required a particular mode of draughtsmanship so that the “production of wood-engraved illustration attracted specific signification in terms of the perceived masculine and feminine qualities of the techniques” (108). Drawing directly onto a wood block was assumed to be a masculine skill, requiring a firm decisive hand; wood engraving on the other hand suited women’s dexterity and their imagined lack of creativity, a task for an artisan rather than an artist.(15) It is another sign of Florence’s daring that, according to Ellen Clayton, she decided to do “what no female artist in all the world had attempted before – made a drawing on wood for a weekly illustrated paper. … There were ladies who engraved, … which involved a very unpleasant amount of hurry, bother, downright drudgery, and ‘night work’. … But as yet no woman had thought of trying to solve the mysteries of preparing and executing a wood-block” (44-45).(16) With a need to earn more money, Florence Claxton apparently wanted to push the boundaries of what work was suitable for women. Illustrations were perceived to be a lesser form of artistic achievement than “proper” paintings, but she could at least encroach in this way into male territory and thus increase her earnings. She and her sister Adelaide were soon supplying numerous witty drawings for a variety of periodicals, particularly London Society, illustrating both topical articles and fictional stories. Their names became sufficiently well known that they featured in advertisements as selling points.

<14> By commissioning Florence Claxton to illustrate Charlotte Yonge’s serial, Hogg surely believed he had attained a winning combination.(17) There is no evidence that he consulted Yonge in his choice of artist, and her correspondence initially contains no reference to her reaction to seeing events and characters in her story picked out and realized in these black and white images. The Claxtons’s manner of drawing suited the “smart social end of the periodical market and differed from the more self-consciously artistic ‘sixties school’ approach to illustration based on Ruskinian principles of careful drawing from nature” (Flood 113). Their standard type of satirical image would be inappropriate for Yonge’s story and it was vital that, even when the text embellished Rachel’s stubborn pig-headedness and made comments intended to be gently amusing, Florence Claxton did not indulge in ridicule in her illustrations, such as those she had created for Married Off: a Satirical Poem by H. B. (Henry Bergh). Yonge’s style of domestic realism incorporated a more subtle humor than, for example, the type of comic situations created in novels earlier in the century by Mrs. Fanny Trollope, and therefore needed images that elicited sympathy or captured a key event without the use of exaggeration or caricatures.

Florence Claxton’s illustrations for Clever Woman

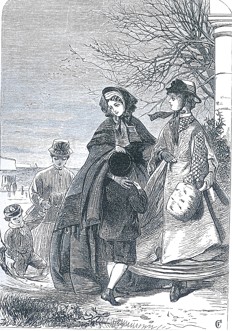

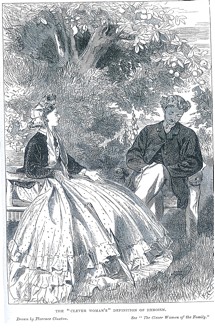

<15> The January issue of Churchman’s Family Magazine opened with a frontispiece “Lady Temple gazing round on the scenes of her youth” (Fig. 1) to accompany Chapter 1 of The Clever Woman of the Family “by the Author of the Heir of Redclyffe” (Yonge’s name is not mentioned throughout the serialization). Claxton indicates the forthright, somewhat critical character of Rachel Curtis, on the right, through her bold upright stance compared to the maternal roundness of her cousin Lady Fanny Temple, who is supported by her eldest son, Conrade. Meanwhile Rachel’s sister Grace helps another son, Francis, up the slope from the beach. Although Fanny at twenty-five is the same age as Rachel, she looks frail because she has been recently widowed and has returned to Avonmouth from India with her seven children (six boys and a baby girl). This illustration successfully sets the scene for the start of the story placing Rachel in a dominant position ready to adopt her mission – initially to take Fanny’s many children in hand. Claxton provides no distinctive features for the women whereby definite identification would be possible in future pictures. This is further exemplified by the charming, naturalistic illustration that graces the opening page of February’s magazine (Fig. 2). It depicts a gentle scene of companionable repose where the invalid Ermine Williams sits in her wheelchair beside some French windows, contemplating her niece Rose playing with her doll, Violetta.

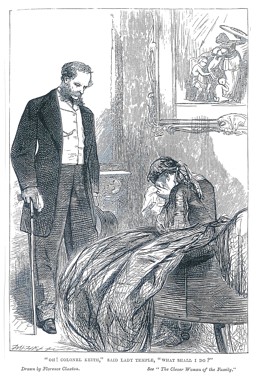

<16> Unlike the common practice in books with illustrations, no indication is given here or in any of the pictures to what incident or quotation each drawing is referring – to page 14 of the magazine for the opening picture in the January issue and page 183 in February. This latter was a long way from the actual illustration as the chapters from Clever Woman wereassigned to the last pages that month. On some occasions, as in the issues for March, April, May, and June, the picture happens to be placed alongside the relevant page, but often the reader is left to search for the words or event to which a picture is providing an image. In July, readers must have been mystified by the illustration placed opposite page 26 and the start of Chapter 9 – “Oh, Colonel Keith,” said Lady Temple. “What shall I do?” – (Figure 3), as this scene does not occur anywhere in that month’s extracts. Only when they acquired their next month’s magazine in August, would they discover the episode in Chapter 11 where Lady Temple utters this plea because she is dismayed at the proposal of marriage from Colonel’s Keith’s elderly brother, Lord Keith (a character who had not yet featured in the previous chapters). This inaccuracy over the placing of the illustrations is confirmation for Simon Cooke’s comments about John Hogg’s failure to ensure that there was strong management of all aspects of his periodical (“CFM” Victorian Web).

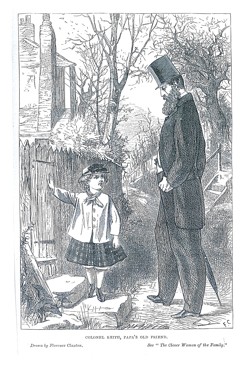

<17> There was another oversight (caused perhaps by Claxton herself not reading the text with sufficient care), over Colin Keith’s appearance. When we are first introduced to him in March as “Colonel Keith, Papa’s old friend” (Figure 4), Claxton gives him a luxuriant beard in keeping with Rose’s exclamation, “Aunt Ermine, there’s a gentleman, and he has a great beard, and he says he is Papa’s great friend!” (60). Yet in later images his “great beard” has been strangely trimmed although comments in the text to his “thick beard” (104) and his “brown beard” (172) continue and there is no reference to its diminished size. Had it been shorn, Yonge would surely have brought it to the reader’s attention, probably via a comment from one of the children. Mrs. Curtis’s observation about Col. Keith as “quite a gentleman all but his beard” (83) is a reminder of the remaining prejudice felt by the older generation against beards as marking out men who were either disreputable or artists or foreigners.(18)

<18> Such inaccuracies may well have contributed to Charlotte Yonge’s eventual dissatisfaction with the pictures in the Churchman’s Family Magazine. As an experienced editor, Yonge would have been aware of these lapses.(19) We have no record, however, of her opinions in the early months, and it is possible that she did not object to the nature of the first illustrations. Claxton’s pictures in April and May (Figures 5 and 6) highlighted key embarrassing incidents between Rachel and Captain Alexander Keith with some subtlety. Figure 5 depicts Rachel lecturing Alick on true valor, believing him to be merely a young idle soldier on leave. She had previously been expounding her lofty ideas about how boys should not play at battles as it accustoms them “to confound heroism with pugnacity” (80). Defining heroism as “doing more than one’s duty,” Rachel decides to give this “young carpet knight a lesson in true heroism” (81), and proceeds to describe an actual incident of outstanding courage from the recent siege in Delhi, unaware that Alick was the very man whose courageous deeds she is recounting. Claxton captures the humor of the situation well, showing Rachel urgently delivering her homily, unaware of why a blushing Alick looks discomforted. Similarly, Figure 6 illustrates a moment of dawning truth for Rachel when, in the process of swatting a daddy-long-legs, she discovers that Alick’s gloves disguise military wounds of a scarred left hand lacking some fingers. Just before this she had been amazed to learn that he was older than her, had been in the army for ten years and thus all her preconceptions turn out to be wrong. Claxton’s illustrations of Rachel’s behavior towards Alick add to the reader’s appreciation of these occasions.

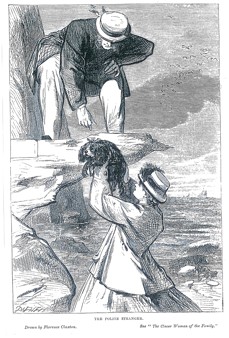

<19> “The Polite Stranger” (Figure 7), the illustration for June, is in many ways the most effective picture that Florence Claxton created for Clever Woman. This shows Rachel stranded on some rocks by the incoming tide through her determination to save a dog that belonged to one of Fanny’s boys. A man who has been sketching on the cliff-top comes to her rescue. This is a crucial moment in the novel as this is Mr. Mauleverer, the stranger who will figure as the villain of the story and will fraudulently cheat Rachel of the money intended to promote a better life for the girls in her industrial school. By positioning him bending down to take the dog, his face is masked by his hat so that we are given the impression of a benevolent, gentlemanly gesture. We, as well as Rachel, are being fooled. Claxton’s depiction of Rachel is also more sympathetic here, allowing her softer, caring nature to emerge in the situation.

<20> While misplacements and inaccuracies likely irritated Yonge, such matters were of minor importance compared with Cooke’s identification of Hogg’s “limited influence over the illustrators’ choice and treatment of their subjects. In practice, there are several occasions where the visual texts are anything but closely matched with their letterpress, a tendency that can be found in many illustrated periodicals of the period, but in this magazine is allowed to run out of control” (“CFM” Victorian Web). Cooke also identifies a more serious fault than a mere mismatch between the placing of pictures and relevant incident, where an illustrator glosses a text with their own interpretation – “a matter of visual expansion in which the image extends or modifies the messages contained in the writing” (“CFM” Victorian Web). Claxton’s illustrations for the later chapters certainly incorporate images that embody a reading of Yonge’s story contrary to her own values or to the details of her text. This is especially true for her choice of clothes for Rachel in Figures 8 and 9, and is of importance because they can provide a visual representation of her character.

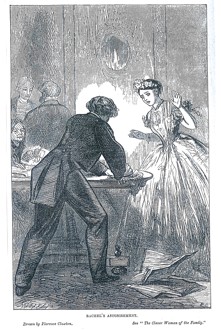

<21> Figure 8 spotlights yet another episode of acute embarrassment for Rachel. During a dance at Lord Keith’s house, she at last realizes the extent of Alick Keith’s heroism. She is shocked to notice a medal gleaming on Alick Keith’s chest. His nonchalant reply to her question, “That is not the Victoria Cross?” gives the title to the picture: “Then it is, like all the rest, a delusion” (Yonge 178). While Claxton was right to choose this moment for illustration, she was wrong to give Rachel such a low-cut décolleté evening gown. This might well match fashion-plates for what ladies in the metropolis were wearing, but does not fit the text that specifies Rachel’s reluctance to attend this Ball, “So, all she held out for was, that as she had no money to spend on adornments, her blue silk dinner dress, and her birthday wreath, should and must do duty” (176). Elsewhere Yonge refers to “Rachel’s severely simple and practical tastes” (339). Rachel only begins to take care over her appearance towards the end of the story where she learns to develop her femininity in the warmth of Alick Keith’s affection.

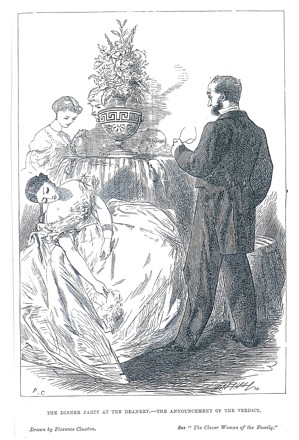

<22> Rachel’s evening dress as drawn in the illustration for December 1864 (Figure 9) seems even more unlikely. By this point she has been humbled and disgraced by the terrible outcome of the mistreatment of the girl apprentices. It is the week of the Quarter Sessions at Avoncester and Mauleverer (real name Maddox, the very man who had swindled Edward Williams, father of Rose and brother to Ermine and Alison), together with the women he had employed, are on trial. Rachel, feeling shamed and humiliated, wants to miss the ordeal of dinner at the Deanery but is persuaded to attend for the sake of appearances. It is inconceivable that Yonge would have dressed Rachel looking in this way for an unhappy scene in such a venue. Claxton has reverted to the type of cartoon-like drawing of fashionable women that she and her sister provided so often for London Society, more suitable for Punch than for the portrayal of serious-minded Rachel. Yet Yonge is careful with her precise descriptions of clothes to create vivid images that relate to a particular personality. Thus at the Huntsford Croquet Party she characterizes the flighty frivolity of Bessie Keith: “She was one mass of pretty, fresh, fluttering blue and white muslin, ribbon and lace” (305), making this very outfit the marker for Bessie’s inappropriate conversation with a young man and the cause of her fatal trip, leaving her “entangled in her dress, …much torn … and hung in a festoon” (307). A comment Yonge made in 1879 in a letter to Alexander Macmillan about a version of The Heir of Redclyffe illustrated by Kate Greenaway suggests that she often felt annoyed by the interest shown by illustrators in modish clothes: “Thanks for the copy of the heir [sic] of Redclyffe which is very prettily got up and attractive. I never yet saw an illustrator who would avoid the height of the present fashion.”(20)

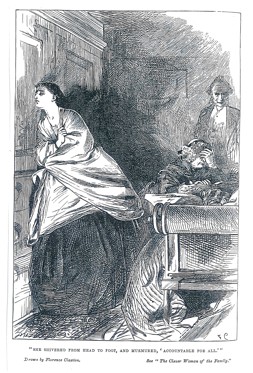

<23> The proof that Yonge did not like Claxton’s illustrations is contained in a letter she wrote to Macmillan in October 1864 about the arrangements for his firm to publish the story as a book: “The Clever Woman of the Family as far as she goes will be sent you in a day or two from a friend who has had her to read. The illustrations are decidedly not successful and I should not wish to perpetuate them. They are not half so good as what Miss Keary’s young cousin does.”(21) Miss Keary’s relative was Katie Johns, the daughter of the Rev. Charles Johns, himself a noted painter of wild flowers. Katie was a proficient artist but, more important for Yonge, she would be susceptible to guidance being a member of the “Goslings” over whom Yonge as Mother Goose acted as tutor and mentor.(22) Yonge came from a section of society that favoured personal recommendations as a first step to most transactions – employing servants, appointing teachers and making new connections. She would favour Katie Johns because she knew her family.(23) It is also possible that Claxton’s illustration for that month caused Yonge particular anguish. Entitled, “She shivered from head to foot, and murmured ‘Accountable for all’” (Figure 10), it depicts the tragic scene of Lovedy Kelland’s deathbed. It is an image that prompts reminders of contemporary narrative paintings where women who have sinned are contemplating the consequences of their conduct and are wracked by guilt. Not only the image and its resonances but also the particular sentence selected may have been objectionable to Yonge. Claxton could have chosen a different text to illustrate the same scene, perhaps one that provided more spiritual hope such as Lovedy’s request for prayers, or Rachel’s, “Oh, forgive me forgive me, my poor child!” (Yonge 231).(24) Adrian Stokes’s frontispiece for the 1880 edition of Clever Woman highlighted instead a moment of redemption, “Lady Temple carrying off Lovedy and Mary,” when a demure but determined Fanny rescues the two children from the sweated labor of Mauleverer’s establishment (217). We have no record of Yonge’s opinion on Stokes’s illustrations, but it is highly likely that she would have preferred both his choice of incidents for depiction and the seemliness of his images that were more in keeping with her implicit messages.

Conclusion

<24> Yonge’s dislike of Claxton’s pictures should not be interpreted as a judgment on her attitude to women working as artists. Her correspondence reveals how she rarely liked any illustrations chosen for her books, whether they were drawn by women or by men. For example, in January 1868 Macmillan wrote to her (referring probably to Edward Armitage’s pictures in the Pupils of St John the Divine), “I am very sorry you do not like the illustrations. … I hope you will get reconciled to them by and by.”(25) Yonge was critical even of those by her friend Jemima Blackburn: “I am glad you decided against illustrations for the Little Duke. Mrs. Blackburn’s were not very successful … Those to the Lances of Lynwood are much better, but she is never really at home without animals as her subject.”(26) It was a rare occasion when Yonge praised illustrations, and even then she would add criticisms, “Most of these illustrations I like very much, they are full of life, … but the faces of Eleanor in the second and of the Page in the first are rather distressing, and I think that in the second the Page is rather too short and stocky to give the notion of one who was to grow up tall enough to be taken for the king.”(27)

<25> Yonge’s major novel, The Pillars of the House (1873), provides ample evidence of her knowledge of the restrictions on talented women studying to be artists. She portrays Geraldine Underwood sympathetically as a would-be artist who, without any of the advantages of her brother and fellow-artist Edgar, steadily gains recognition. One of Geraldine’s paintings in a Royal Academy Exhibition receives “the most ambitioned praise a woman can receive,” when a male viewer comments, “There’s so much power as well as good drawing and expression, that I should not have thought it a woman’s work” (Pillars 2: 109). Meanwhile Edgar squanders his talent, leaving Geraldine to use her artistic abilities to earn sufficient money to pay off her brother’s debts. With extraordinary resonances to Florence Claxton’s paintings, both that of the Pre-Raphaelites and of Woman’s Work, Geraldine creates a picture whose theme is the “Rights of Woman”: “… two cartoons. One was a kind of parody of Raffaelle’s School of Athens, all the figures female, not caricatures … The companion was arranged on the same lines, but the portico was a cloister, and the aisle of a church was dimly indicated through a doorway” (Pillars 2: 362-63). Geraldine then voices Yonge’s own conviction: “while woman works merely for the sake of self-cultivation, the clever grow conceited and emulous, the practical harsh and rigid, … and it all gets absurd. But the being the handmaids of the Church brings all right” (363). Her brother Lance adds, “it might as well be man as woman” (363), and indeed Yonge was always as critical of men as of women who worked for selfish ends rather than for the wider community. From many of her novels we can deduce that Yonge approved of young women who contribute to their family’s income where necessary and, if money was not required, they should devote themselves to unpaid work for family and community. She understood how shifting social conditions meant that young women faced new challenges. The straitened circumstances of her only brother in the 1870s meant she had personal experience of providing financial support for family members. Therefore it is feasible that Yonge would have applauded how Florence and Adelaide Claxton worked as artists for the benefit of their family.

<26> Neither should Florence Claxton, because of her championship of women’s right to equivalent artistic training as men, be categorized as a radically-minded woman with viewpoints diametrically opposite to those of Yonge. Indeed her satirical cartoon, The Adventures of a Woman in Search of Her Rights (1872) can be read as an attack on progressive women. It depicts the disasters that ensue when they attempt to strike out on their own. One of the final drawings, where the “advanced” woman is departing for America, is captioned sarcastically, “Leaving her wretched countrywomen to their former trivial and degrading pursuits” (16). It shows a scene not of misery but of a happy mother sitting beside her hearth with her children and cats, in the bosom of the family.(28) This “wretched countrywoman’s” domestic contentment is in stark contrast to the miserable appearance of the “advanced” woman who has caused mayhem by her “search for her rights.” The picture that ends this short comical book is of a young woman waking up in her bed, saying, “THANK GOODNESS, IT’S ONLY A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM – and I’m NOT emancipated” (16). By the time this was published, Florence was married to Ernest Farrington and according to Ellen Clayton “withdrew from the profession, and now makes no claim to be considered as belonging to the artistic world, though occasionally exhibiting” (Clayton 44).