<1>This is the improbable story of how, in the midst of a terrifying global pandemic, I learned how to be a better teacher by letting my students grade themselves.

<2>The story follows a protagonist, me, as she tries to solve the riddle of teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic in accordance with a single, deceptively simple principle: do no harm. I figured it like this. My students were going to get sick, and members of their families and chosen families were going to get sick. Some of them might die. The students would have care responsibilities, or have to bear the weight of not being able to care for someone they love because they were far away or it would be unsafe to do so. They would feel, at a minimum, that constant, thrumming, low-level anxiety and malaise that comes from global uncertainty, the unrelenting threat of deadly disease, and intense social isolation. I expected that more than a few students would wind up having full-scale mental health crises. To do no harm meant, to me, designing courses that did not make any of this worse by adding stress or exacerbating feelings of lack of control. It meant, furthermore, to take a very small step in the direction of making things better by offering students the resources to cut themselves some slack under extremely sub-optimal conditions for learning and backing those resources up with a relaxed, flexible, and compassionate attitude towards showing up and turning in assignments.

<3>I wish I could say that the story ends with a solution to the riddle of how to teach remotely during a period of crisis while doing no harm. It does not. What it offers instead is an account of an experiment I tried that was designed to offer my students more control over their grades in the course and, by extension, their individual approaches to the learning process. In my Fall 2020 courses at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where I teach in the Departments of English and Communication Arts, I asked undergraduates to set their own goals for their participation in the course, reflect on and assess their progress towards meeting those goals throughout the semester, and then assign themselves a final participation grade based on their performance. This activity was the centerpiece of what I described to my students as my pandemic pedagogy, which I promised would reward “regular, good-faith engagement with the course material and with each other” over major assessments like essays and exams. To this effect, half of their grade for the course came from their “participation”—the grade they determined for themselves—and low-stakes assessments graded on completion rather than merit. The discussion posts they wrote reflecting on their participation were part of this low-stakes assessment. I was transparent with the students: my agenda here was to elevate their grades. I was neither interested in failing anyone nor in punitive grading during a global emergency, and I hoped they would set achievable goals that they could give themselves full marks for completing.

<4>In what follows, I will report on my participation exercise and how it played out in the courses I taught in Fall 2020: a seminar-style introduction to literature course called “Visual Storytelling,” taught synchronously in the Department of English, and “Global Cinema History,” a hybrid synchronous/asynchronous lecture course taught at the intermediate level in the Department of Communication Arts. I will draw on the experiences of my students, in their own words (used here with their permission), to describe the strengths and limitations of the exercise for fostering engagement, motivation, accountability, confidence, and the sheer pleasure of learning. Finally, I will describe how running a pedagogical experiment like this—low-stakes in all practical senses, high-stakes as an expression of my desire to make a broken world slightly better for my students—caused me to reflect on and evaluate my teaching in unexpected ways. My choice to focus this essay on my own experience and the experience of my students, instead of engaging with scholarship on pedagogy, reflects the emergency conditions under which I developed this activity. I was in a rush. Although I have a background teaching student-centered, inclusive, and anti-racist pedagogy, I did not stop to research the literature on ungrading or spend time adapting existing models of contract, community-based, and specifications grading.(1) I have included a short bibliography to briefly place my exercise within the context of this literature. However, I want to stress that this represents research conducted post facto, as part of an effort to contextualize my pedagogy within other programs designed to unleash the radical potential of student-centered classrooms and dismantle what Jesse Strommel calls “a hierarchical system [of grading] that pits teachers against students” (29).

The Activity

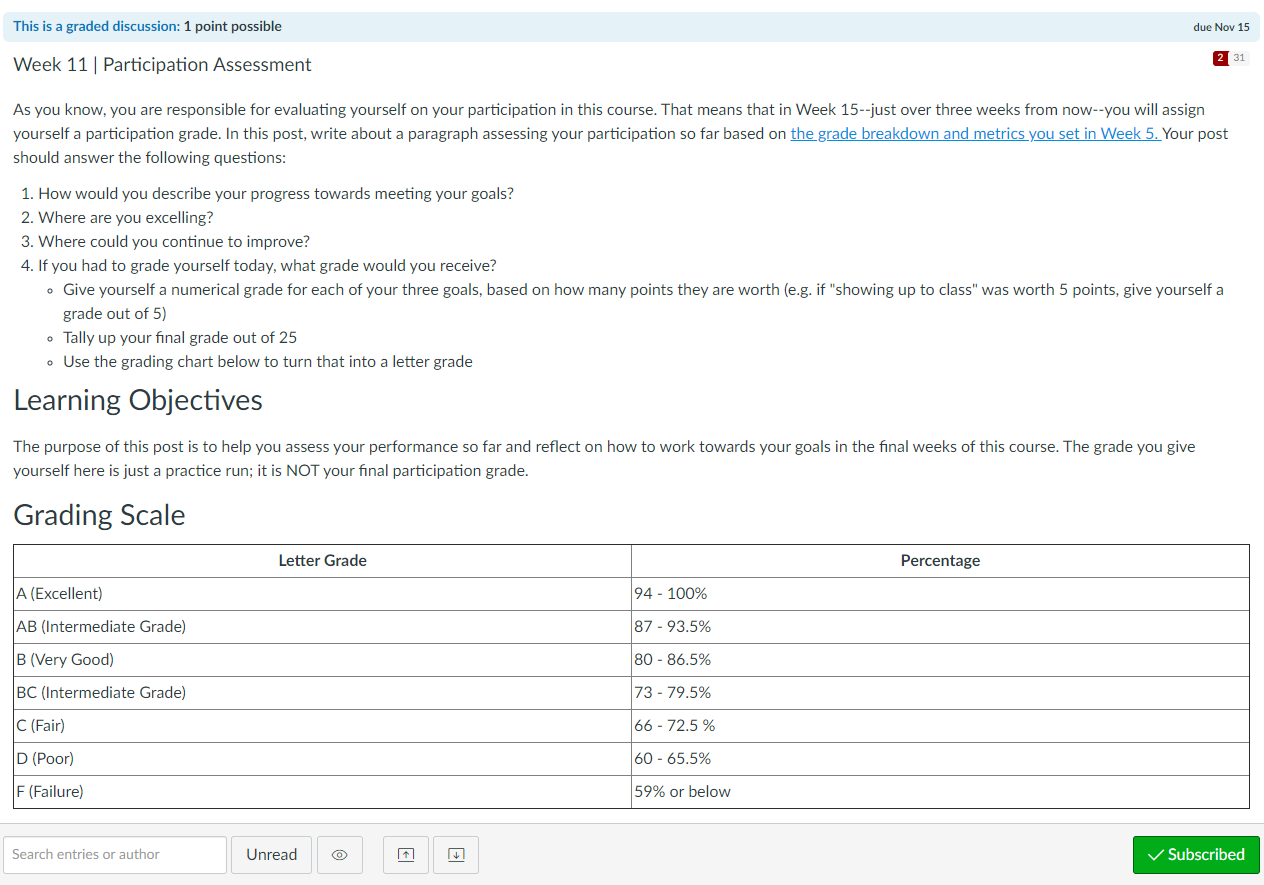

<5>My participation activity consisted primarily of four informal, low-stakes discussion posts spaced out across the semester. In Weeks One or Two, my students set goals for how they wanted to participate in our online course (see Fig. 1). To do this, they were asked to reflect on what classroom participation meant to them, including characterizing the way they participate in class generally and defining areas where they would like to improve. In Week Six, I asked them to refine the participation goals they set at the beginning of the semester (see Fig. 2). They re-read their original post and used it to tease out three concrete participation goals. Just as I would do if I were evaluating them, they were tasked with creating a rubric that assigned a certain number of points to each goal and established what the goal entailed. We checked in again in Week Eleven (see Fig. 3). In this third post, the students reflected on their progress towards meeting their goals, noting areas of excellence and areas for improvement. I also asked them to do a trial run of grading themselves: “If you had to grade yourself today, what grade would you receive?” I supplied a grading chart so that they could translate the number grade from their rubric to a letter grade. Finally, in the last week of the semester, students wrote an evaluation that included a grade and a reflection on what they learned from the participation activity (see Fig. 4).

<6>What this looked like in practice was a variation on contract-based grading in which the students made a contract with themselves—and with me—to work towards specific goals throughout the semester.(2) Many of my students set goals to attend office hours—twice, once before every writing assignment, or for the first time in their lives. Some focused on turning on their cameras and taking leadership roles during breakout group discussions. When it came to speaking in class, many of the students used the opportunity to reflect on their habits to set tailored goals for self-improvement. “Speak up in class about my own opinion,” one student wrote, “Try not to start with, ‘Going off of what ___ said’ or ‘I agree with ___ on this because ___ .’ Although it is good to do this, my goal is to come up with my own ideas.” Others used the exercise to hold themselves accountable to simply completing coursework during a time when their motivation and focus were lagging, such as a student whose rubric read: “Eight points—completing screenings and readings before class. Two points—posting thoughtful and intuitive comments on my classmates’ discussion posts. Ten points—writing thoughtful and detailed discussion posts that convey what I am thinking and how I am relating things to the course material.” I liked that the activity allowed students to make choices about how they engaged with the course and scaled “success” to whatever they thought they could manage under the circumstances. I also liked that it fostered self-consciousness and reflexivity about the process of learning. As Asao B. Inoue writes, “We learn by practicing, thinking about our practices, and re-formulating practice” (“Community-Based” 232). Inoue speaks here about the practice of writing, but his point applies equally to the practice of learning. My exercise asked students to reflect on their individual practices of learning and to ask themselves what they would have to do to make their learning deeper, more meaningful, and more fun.

Student Responses

<7>In their final participation evaluation and reflection, students in both of my courses responded positively to evaluating themselves on participation. 95% of students recommended that I repeat the activity for my online courses in the Spring semester, describing its effect on them in terms of “increased motivation,” “greater accountability,” and the ability “to focus on my learning instead of on my grades.” A few connected the affordances of the exercise to “what is required in the real world. At the end of the day, we have to take responsibility for our goals and what we actually want to get out of this life. We have to check in with ourselves and be able to not only see progress as a motivation to keep going, but also to celebrate how far we have come! I think this activity is a representation of those principles, and I honestly think an element of this should be in every classroom.” When asked to reflect on what they personally learned about themselves through the exercise, the students told me that their semester-long inquiry into how they participate had not only yielded greater self-awareness, but also greater self-confidence. A student who had described herself in the first week as quiet, insecure, and anxious about speaking in class found that “setting a goal to improve my confidence early on in the semester really allowed me to achieve my newfound belief in myself . . . I no longer feel my heart pounding when I answer a question, and I really enjoy being an active participant in our virtual classroom.” Another student identified speaking up in class as a weakness but noted that “once I overcome this fear, my strength is my analysis.” A third “learned that if I participate once, I am more willing to participate several times without any trouble.” For a fourth, the lesson was simply that “I am really hard on myself . . . [I learned] it’s okay to focus on what you’re doing right too.”

<8>I was curious whether this exercise had succeeded in lowering performance-based anxiety and offering students a sense of control in a world where, as one student put it, “we feel a total lack of control.” When I asked them about this, 48% told me that evaluating themselves on participation reduced their stress about grades and performance compared to receiving a grade from the professor. These students appreciated “knowing that I am in control of grading my own participation” and that “I didn’t have to be scared that my participation would be seen as unsatisfactory,” and they felt liberated from normative expectations of what constitutes good participation. “I often find myself stressing out during my other classes and trying to blurt something out just to get participation points,” a student wrote. “Blurting something out just to get the point is in no way meaningful and doesn’t benefit me.” 24% of students reported that the activity had added new stress. These student responses ranged more in the kinds of experiences they were describing. A few students wrote about “a good and productive level of stress” that motivated them to engage more deeply with the course, while others found that watching themselves fail to meet their goals created anxiety and lowered motivation. “I’m already very judgmental towards myself,” one student wrote and continued to say that “While I appreciate the goal of this activity, it was not helpful for me.” The remaining 28% of students reported that the activity neither reduced nor increased their stress. It is striking to me that almost all of these students, including many of those who connected the activity with anxiety and lower motivation, still recommended I use it the following semester. They liked the self-reflection portion, if not the evaluation; or they felt they had sabotaged themselves by setting goals that were too difficult to meet.

What I Learned

<9>This exercise benefited my teaching in a variety of ways I had not anticipated. Reading every few weeks about my students’ learning experiences restored to me some of the pedagogical intuition of which online teaching had stripped me—the one that tells me whether my students are paying attention, whether they are bored or insecure or distracted, and that allows me to regulate the social environment of the classroom so that it works for everyone. I knew, for example, that the vast majority of students in “Visual Storytelling” identified as shy and reluctant to speak in class and that my “Global Cinema History” students were experiencing screen fatigue that made mandatory film screenings exhausting. Students disclosed mental health challenges, quarantine-related burnout, internet bandwidth problems in their parents’ home, and their difficulties balancing full-time jobs with online learning. This helped me adapt my teaching as well as my methods of assessing student performance in other areas, like exam preparation and essay-writing. I learned more about what my students want out of their educations and about the native curiosity and sheer pleasure in thinking that exists alongside their more instrumental desire to parlay their education into a good job. I felt more connected to students whose faces I rarely saw and whom I would not recognize on the street, and this in turn made me a better teacher.

Reflections

<10>I have described the successes and pleasures of this exercise. But when I look back, I also see the glitches. I did not plan ahead for the sexism that led some women to evaluate themselves more punitively and some men to inflate their grades, though as a feminist who has researched and taught on inclusive pedagogy, I should have predicted this. The Week Eleven trial-run in which students tabulated a preliminary grade for themselves was my saving grace, allowing me to use the comment function to run interference. “I would never mark you down for [having internet problems / being depressed / missing a single class session],” I wrote in messages to more than one student, “and you shouldn’t either.”(3) I also explicitly addressed gender bias with my students in class and asked them to consider the value of advocating for themselves. (I did not address grade inflation because I expected it and, moreover, do not take issue with students exploiting the activity to inflate their grade so long as they engage with the process of writing reflections.)

<11>Another issue I was not aware of until the final evaluations and reflections were submitted was the insecurity and stress some students felt about giving themselves “good” grades. “There were many times this semester where I would worry about what the professor would think of me if I over-graded myself,” one student confessed.(4) I wish I had found a way to communicate to my students that this kind of surveillance was not happening; that, in fact, with nearly sixty students I had never met in person in a virtual learning environment, I could not have fairly passed judgment on the grades they assigned themselves even if I’d wanted to. The only adjustments I made to their self-assigned grades was to elevate scores I thought were too low from students whose reflections showed evidence that they were grading themselves too harshly. (When I did this, I always let the student know in a comment.)

<12>More fundamentally, upon reflection, I read the activity as a somewhat ambivalent expression of what I narrated to myself—and have now narrated here—as my guiding principle: do no harm. I told myself that I was trying to reduce worry, stress, anxiety, and insecurity about grades and academic achievement during a period of crisis. But if this was really my agenda, why was I using merit-based grading in the first place? Some of my colleagues were advocating giving all the students As, partly as a refusal to penalize students for their performance and partly in resistance to institutional mandates that we proceed with our teaching as though we were still operating under normal conditions. I stand by the value of a strategy like this on both counts. But I did not use it. Meanwhile, under the same roof as me, my partner was using a version of labor-based grading in his undergraduate game design courses. His students received full marks for their games as long as they met the specifications laid out in the prompt; beyond this, how hard they worked, how much creativity and skill they demonstrated, would not be evaluated. He found that although he played a lot of not-great games, the students came away from the class with greater confidence, pride in their accomplishments, and sense of ownership in their work than if he had graded for quality. Like the “As for everyone” strategy, this approach correctly recognizes that merit-based grading has an arbitrary relationship to learning and achievement, and that learning and achievement can flourish in its absence. But I did not use this strategy either. Instead, I came up with an activity that maintained the conventional relationship between merit-based grading, motivation, and academic achievement by teaching students how to turn the regime of grading on themselves, how to, in essence, internalize the professor’s disciplinary and surveilling gaze. This is what I believe my students were feeling when they told me that the exercise caused them anxiety.

<13>I am not writing this because I want to turn readers against a structured self-evaluation exercise like this one. I thought it worked quite well, and my students did, too. For every student who reported increased anxiety, there were two more who reveled in the “good stress” and the freedom to learn on their own terms. Moreover, I stand by the political work that an activity like this performs. As long as merit-based grading exists, taking the power to bestow merit out of the hands of the professor and placing in the hands of the individual learner is a meaningful form of subversion that provides students with the tools they need to critically analyze the prevailing ideologies of university education. I am offering this critique of my own activity instead in an effort to hold myself accountable to the same practice of self-reflection I asked of my students. Looking back, I believe this activity was as much an expression of my ambivalence about grading as it was a pandemic-era adaptation. While I told myself that the exercise exemplified my political commitment to “do no harm,” it was also an attempt to explore the relative harms and benefits of merit-based grading for student learning under the conditions of stress, emotional and psychological strain, and unprecedented normalization of economic and existential precarity that characterizes our students’ coming-of-age in late capitalism. Given these circumstances, does merit-based grading simply reinforce a punitive capitalist logic that turns student work into alienated labor and prepares them for contribution in an alienated workforce? Or is it possible to salvage merit-based grading by leveraging it as a tool for formative self-assessment and personal growth? Am I really allowing students to flourish intellectually and creatively when I teach them to assign each of their goals a number of points and to equate their learning experience with a letter grade? Can learning in today’s distracted world happen in the absence of “good stress,” and can I create something like “good stress” if I grade, for example, for labor instead of merit?

<14>As promised, this story does not end with any clear answers. But it does end with questions—questions that are the promising fruits of this deeply unpropitious time for teaching. I let my students grade themselves and became a better teacher, not only in the short term, but by allowing myself and my students to treat the class as an experiment, to try and fail and reflect, and to ask ourselves how we might do better.