<1>The pedagogical benefits of annotation are well documented.(1) Students who take notes as they read, rather than only underlining or highlighting, engage more closely with a text and retain more of what they read. Technology provides opportunities to make the once-private experience of annotation a collaborative activity, bringing students and faculty together over a shared text, and, as online education specialists Monica Brown and Benjamin Croft suggest, offering opportunities to “subvert the traditional hierarchical structure of knowledge at the university.” While these strategies have improved my students’ reading, another form of annotation has had an equally powerful effect on my students’ engagement with the course and texts. Annotation tools in Zoom allow students to contribute to class activities by adding text, stamping icons, and underlining and highlighting text on the slides I display.(2) With these tools, we work together to define new terms from secondary reading assignments, visualize patterns in genres published in nineteenth-century periodicals, visually share opinions about the assigned reading, and mark particular words or phrases in excerpts from our primary texts.

<2>Each time we use Zoom annotations in class, the discussion that follows is far richer than anything I could present in a lecture or draw out in a discussion where only the usual, outgoing students answer based on their reading. These activities broaden the number of student participants and engage most, if not all, members of the class. A glimpse of the screen during one of these activities makes evident that students who remain silent have actively participated in the discussion. This form of engagement promotes a level of equity impossible through most other classroom engagement techniques. Students uncertain about joining class from places where they cannot show their video or unmute their microphones to contribute verbally are still actively participating, not only listening to what their classmates and I are saying.(3)

Breaking the Ice with Zoom’s Annotation Tool

<3>In Fall 2020, I taught Senior Seminar, a capstone course for twenty-five literature and humanities majors graduating in Spring 2021. The first half of the course focused on digital humanities and nineteenth-century transatlantic literature before students developed a capstone paper and project on a topic of their choice. My university only held in-person classes where necessary, so this course met twice-weekly in synchronous Zoom sessions. Like many other educators, I spent my summer reading books and articles, listening to podcasts, and attending any professional development activities that would help me to improve my online teaching for the Fall.

<4>Less than two weeks before our Fall semester began, Brian Alexander, in his August 6, 2020, installment of the Future Trends Forum, talked with Nancy White about facilitating effective videoconference experiences.(4) White described her efforts to help participants overcome the ways that technical difficulties “compile to make them feel very inadequate” by having them play with new tools. In setting up the use of annotation in Zoom, she describes the value of “put[ting] up a coloring sheet before the session starts,” which surprises and confuses the participants. White uses this as scaffolding to prepare them for using “the stamping tool to understand whether there’s convergence or divergence of thoughts” among the group.

<5>In the first week of the Fall semester, White’s words came back to me as I planned our first whole class discussion of readings. In a usual semester, I would ask students to read for homework several scholarly articles about the field of digital humanities and call upon them to agree as a class on a working definition for the term. In an in-person class, this is a difficult task, but in a Zoom meeting, it seemed impossible. I decided to try an experiment based on White’s ideas.(5) We started the class with some annotation practice on a slide that I divided between a coloring page pulled from a quick internet search and some blank space. Students typed hellos in a rainbow of colors, stamped icons around the screen, and painted a black and white line drawing of Peppa Pig designed to be printed and colored by hand. They felt the surprise and confusion White described, and it was messy to have over twenty people adding things to the same screen. We laughed about the experience and broke the ice at the start of a new course and semester.

Annotation to Enhance Learning and Participation

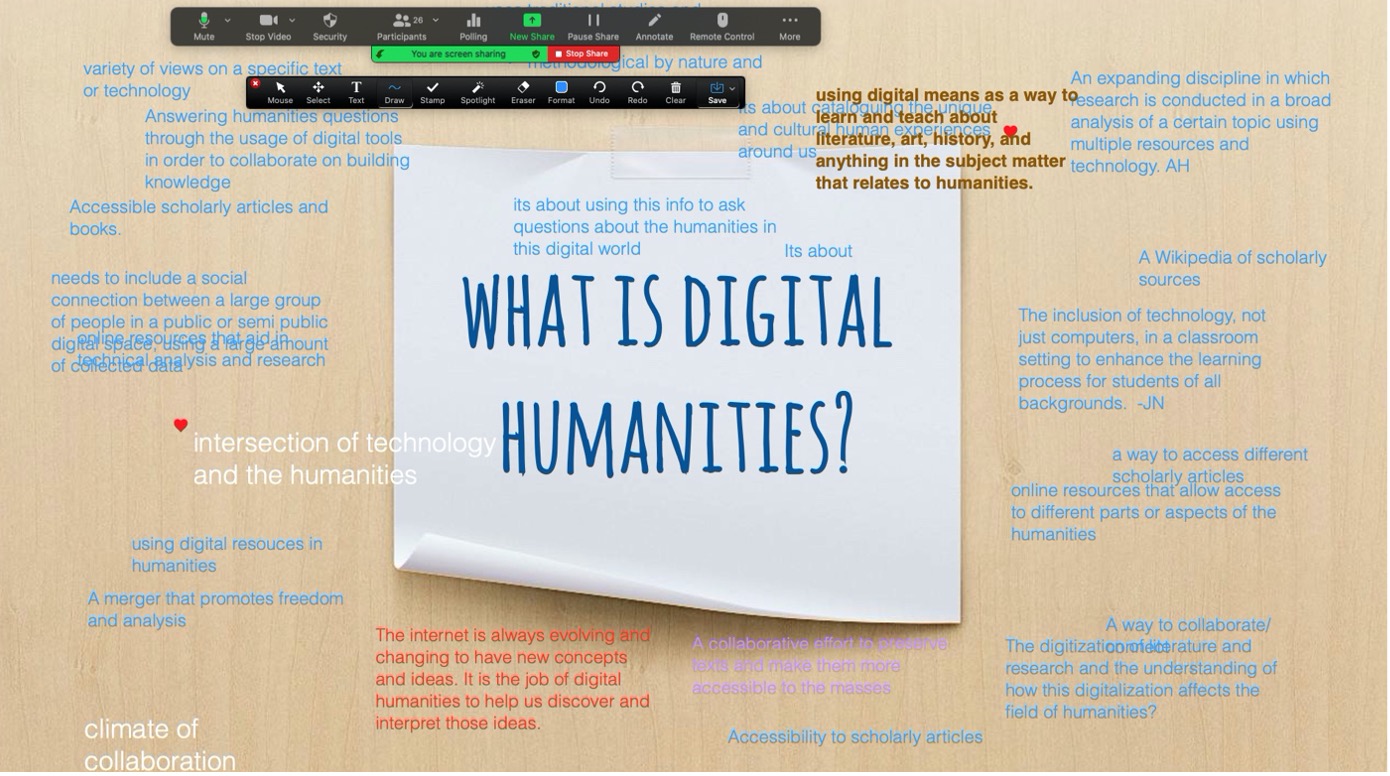

<6>When it seemed that everyone was relatively comfortable with this new set of tools, we switched to a screen with just the words, “What is digital humanities?” I gave the class five minutes to review their notes on the readings and type onto the screen any phrases they thought should be considered in understanding the concept (see in Fig. 1).(6) Their words overlapped each other with some incomplete phrases, but the screen included twenty-four unique responses to the question, the same number as students in attendance. Once the posts slowed, we took an additional few minutes to silently read the responses and reflect on them before having a verbal whole-class discussion. The annotation activity had the dual effect of helping students gather their thoughts, as in a warm-up writing activity, and giving them confidence in seeing what their classmates thought before they responded verbally. Though fewer than ten students participated in the verbal discussion, and about fifteen had cameras turned on, it was clear that the whole class was engaged.

<7>Over the course of the semester, the students and I developed our comfort levels with Zoom technology. I learned what kinds of questions and activities are best suited for virtual synchronous discussion and the tricks for best facilitating it. Some of these include enabling annotation at the start of every class meeting, as the setting did not carry over from one session to the next, and moving the Zoom toolbar covering some responses before saving the annotations (see in Fig. 1). The students developed their own best practices for responding, including dealing with the limited ability to adjust a typed response if it overlaps with another person’s (only while editing) and learning that their coloring of each class meeting’s coloring page (a new tradition in our course) could be more precise if using a touchscreen device.

<8>Certainly, chat features also allow for students to type responses to discussion questions, but, in my experience, on-screen annotation offers a few key benefits over chat. First, typing onto the screen allows students to avoid the anxiety around giving an incorrect answer by responding with some degree of anonymity. In Zoom, when the student posts an annotation, I see their screenname hover over the words for a few seconds and get a sense of who is participating, but then any indication of whose words they are disappears. Additionally, annotation makes it possible to see all of the responses on the screen at once rather than scrolling through a chat log. Finally, having the responses on the screen allows the class to perform follow-up activities with them. As we refined our use of the annotation tool, we added to the definition activity, for example, by stamping with checkmarks, hearts, and stars around the words and phrases that seemed particularly important or represented trends across the responses.

<9>Visual and verbal contributions in synchronous video classes raise issues around privilege, accessibility, and privacy. Since our campus moved to remote learning in March 2020, several surveys of students in my classes indicated that students have a variety of reasons why they cannot display video or speak verbally in class. For my students, challenges around class participation come from unstable internet connections, lack of access to a webcam, background noise at home, inability to join class privately, and general anxiety and shyness around volunteering to speak in class. The apparent lack of participation does not mean that these students are not engaged in the class meeting.(7)

<10>In written reflections about their participation a few weeks into the semester, more than half of the students in my classes mentioned the use of annotation tools in Zoom as a part of their engagement with the course. They ranged from saying they “enjoy using the annotation tool during class” to “absolutely loving the annotating” and finding it a “fun . . . easy way for me to remain engaged throughout each class.” Most students described the difficulty of “buil[ding] up confidence to unmute . . . and answer questions,” which they found harder than raising a physical hand during an in-person class, so they “appreciate[d] having the chance to contribute” through annotations. As one student reflected, they “participate[d] a lot in the classes where we have the annotation exercises.” They continued, “Being able to type out my thoughts first helps me be able to speak about them, and interacting in general, even just with a stamp tool, makes me more likely to want to interact by speaking. It is also helpful to see what everyone else has written so that I can elaborate on ideas I didn’t even consider until I saw them.” These reflections affirmed my decision to incorporate Zoom annotation into my classes, making clear the effect on students’ level of comfort engaging in the course. In fact, some of the particularly shy students would struggle to participate verbally regardless of whether the course is in person or remote, so the option to contribute anonymously via the annotation tool in a synchronous class actually allows those students to engage more fully in Zoom than in an in-person class.

<11>Returning to Brown and Croft’s points about the use of “social annotation in open pedagogy that centers equity,” I believe that annotation in videoconferencing platforms like Zoom offers some of the same potential for faculty who seek to decenter their classrooms and use technology to engage all students. As with any pedagogical practice, on-screen annotation will only be inclusive if it is scaffolded to ensure all students can participate and structured to encourage truly collaborative construction of knowledge. With intentional prompts and carefully selected activities, sharing the screen with students has the potential to make synchronous online courses more equitable and to give every student a voice in the course.

Sample Activities for On-Screen Annotation

<12>In the sections that follow, I share four applications for the Zoom Annotation tool from my experience and include screenshots from my own classes to illustrate the results of such activities.

<13>Introducing a New Topic: When beginning a new course or unit or introducing an unfamiliar term or concept, I prefer to involve students in creating a shared understanding or working definition. Through these activities, students are more engaged and tend to better conceive of the term and its applications. I assign an overview or introductory reading for homework to give the students a chance to grapple with the new ideas on their own. Then, together in class, we discuss the key ideas or elements of the concept that should be included in our class definition. In an in-person class, I capture these ideas on the board or by typing on my projected screen. In a class on Zoom, I display a slide with just the term or a general question and give students five minutes to use the annotation feature to type key words or phrases that we should consider as part of the concept. Their submissions can be in their own words or quotations from the shared reading. I read the entries as they appear on the screen (see Fig. 1). Then, when the time has elapsed or the submissions seem to stall, I ask them to review everyone’s contributions and use the stamping feature in the annotation toolbar to mark—usually with a heart, star, or check mark—the items that seem particularly important or are trends across the screen. We follow this with a discussion of the term and come to some level of consensus on what seems most important to the class in our understanding of it.

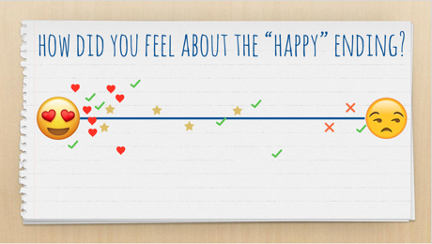

<14>Close Reading: When discussing a primary text in an in-person class, I would expect students to look at specific passages as we perform close readings of the section. This process has evolved from physically writing in the margins of a purchased text or adding sticky notes to rented copies or ones they hope to sell back at the end of the term. In recent years, some students have brought digital copies on laptops, tablets, or phones, and they may be accessing a course text through one of the collaborative annotation tools like Perusall, Hypothes.is, or COVE Studio. For a synchronous close reading on Zoom, however, I prefer for everyone to start with a clean, shared copy of the passage, which I display via Zoom’s screenshare feature. Then, I read it aloud while students stamp beside or underline, circle, or box in key words or phrases. This activity can be organized with certain colors or shapes for particular ideas or completely free-form. Students often need a few minutes to complete their annotations after I finish reading the passage. Afterwards, we discuss the selection, focusing on words and phrases they marked. For quiet students, seeing that others marked the same section they did can give them confidence to share their thoughts in the class discussion.

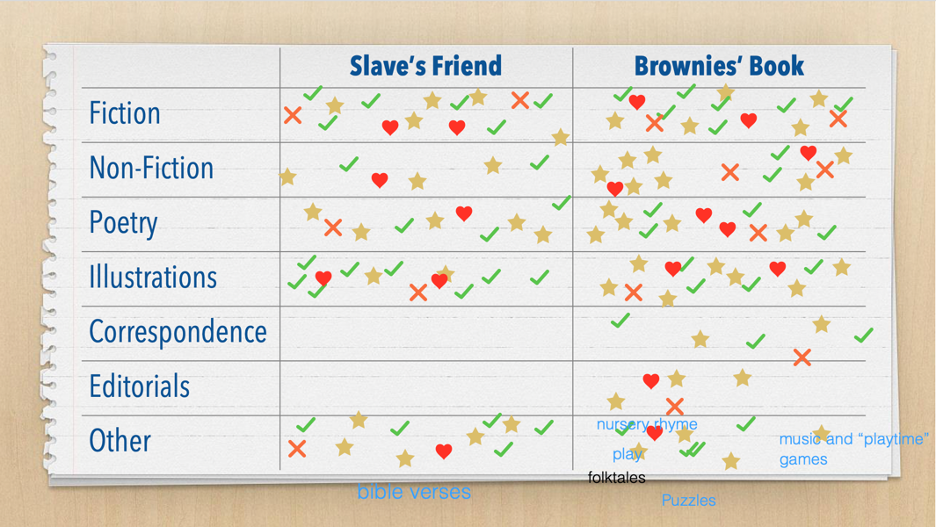

<15>Distant Reading and Data Visualization: When introducing quantitative ways of exploring literature, many of my undergraduate students initially struggle to understand the smaller-scale applications of reading for trends or patterns in a text or group of texts. As we read scholarly essays and book chapters about analysis of datasets with thousands or even millions of data points, they tend to see distant reading as something beyond their grasp. In-class annotation offers the opportunity to visualize the data from their readings for the day or week. By displaying charts or other graphic organizers on a shared slide, I can create a framework where students can stamp their own observations, and within a few minutes, we have a visualization. The process of stamping allows them to connect their own individual experiences to the framework, and then a few minutes of viewing the stamps added by the whole class allows them to see their own observations in the context of their peers. The discussion that follows allows us to step back and see larger trends before shifting to close readings of specific examples. In the example in Fig. 2, students had reviewed sample issues of two periodicals created for children—the Slave’s Friend (1836–1838) and The Brownies’ Book (1920–1921)—and stamped to indicate which categories were represented in their assigned issue, The “Other” section was initially intended to have only stamps, but students wanted to share the types of things that appeared in each periodical. The resulting discussion allowed students to deeply analyze the effects of time period, intended audience, editor, and purpose on the contents of the two periodicals.

<16>Polling Students: Though there are many ways to poll students through videoconferencing platforms and outside tools, on-screen annotation has become my preferred vehicle for doing so. In Zoom, polls must be set up in a web browser, separate from the meeting, which can make them difficult to manage. Another option for gathering student responses is by using the nonverbal feedback buttons (“Yes,” “No,” “Go Slower,” “Go Faster,” and several emojis); however, each person’s response is directly tied to their name, making anonymity impossible. Simply adding a slide to my presentation that asks a question or invites a response is a relatively easy way to gather quick feedback, especially if students are already comfortable with Annotation tools from other class activities. The slide or instructions need to make clear how or where students should indicate their responses. Stamping is the easiest way to do this, and including spaces for each response can be helpful. A simple “yes-or-no” question may have two large boxes, one for “yes” answers and one for “no” answers. A visual question may have multiple images that students can mark to indicate a preference. Because these sorts of questions can arise spontaneously from class discussion, I keep a few voting slides (see Figs. 3-5) at the end of my presentation and can quickly gather feedback from students. These slides are purposely created without specific content to provide flexibility to ask anything, regardless of the day’s topic. Thus, the questions I ask range from logistical questions about the course (for example, whether students would like to shuffle reading groups in Perusall), reactions to assigned reading (for example, how they felt about a particular text or character), or how confident they feel about a given topic (for example, whether they feel they could explain a concept to a classmate). Some are simple votes, but sometimes I also ask students to vote on a continuum to give more nuance to their responses (see Figs. 5 and 6).

Taking the Benefits of Annotation back to Hybrid and In-Person Classes

<17>Four weeks into the Spring 2021 semester, one of my courses moved from fully remote to hybrid, and five of my twenty-six students chose to attend in person in one of our newly-created Zoom classrooms. Almost a year to the day after we abruptly moved to remote learning, I dreaded a return to the classroom, primarily because I had seen the potential for engaging all of my students through these tools and worried about returning to an environment where the same few students volunteered to speak and the rest of the class remained silent. As we prepared ourselves for the change, students would casually mention in the Zoom chat how much they would miss various aspects of our course’s online engagement, and it was clear we needed a bridge to maintain the classroom community that had developed. I confirmed that the in-person students could bring a device (laptop, tablet, or phone) to access Zoom while in the classroom, which allowed us to maintain our use of annotation tools and chat and thus remain connected regardless of how they join the course. The tools in Zoom continue to ensure a sense of equity among my students, as their words or stamps on the screen are no different if they have returned to campus or are unable to leave home due to medical conditions, at-risk family members, or financial constraints.

<18>As we anticipate returning to a new normal with primarily in-person classes in the 2021-22 academic year, I look forward to replacing the muted silences of Zoom with a few audible chuckles at my bad jokes, murmurs of agreement when a classmate makes a good point, small talk before and after class as we get to know each other, and the glorious din of small groups scattered around the room working on activities. Still, I cannot leave behind the pedagogical benefits afforded by Zoom in making a space for the students who remain muted by their shyness or uncertainty, even in a face-to-face class, to contribute to the knowledge building that happens in a decentered classroom. Our considerations of equity as it shapes a student’s engagement in remote classes should join us in a return to the physical classroom as we use technology and other tools to create spaces where all students feel comfortable participating.