<1> A subtle representation of the threat posed by the New Woman is evident in an 1892 cartoon from Punch depicting a New Woman with a top hat (Figure 1). Here, a New Woman in rational dress, including a tailored coat and bow tie, holds a man’s top hat that has been appropriated and repurposed. With a wide bow around the brim and a bouquet of flowers emerging out of the upturned hat, the New Woman holds the makeshift vase as if she is presenting it to the viewer as an offering. Echoing corset advertisements, which prior to the 1870s often depicted disembodied corsets, sometimes filled with flowers or surrounded by cupids and butterflies (Kortsch 58), this cartoon mocks the New Woman’s offering, implying that while it may be beautiful, it is nonetheless trivial and foolish.

<2>Like similar parodies of the New Woman, the cartoon aims to defuse the threat she represents by suggesting that rational dress is simply an aesthetic statement, and that dressing in “mannish” clothing has no implications beyond the decorative or ornamental. Cartoons poking fun of the New Woman’s infamous “bicycle suit,” for instance, suggest that it constitutes an aesthetic choice rather than a utilitarian one. In this respect, it is significant that in the cartoon above, the subject never wears the item she has appropriated, but instead imbues it with ornamental potential. Whereas rational dress reformers envisioned significant changes for women in terms of freedom and mobility as a consequence of their more hygienic, or healthful, dress, parodies suggest that the transformations such dress affords are merely superficial.

<3> But despite the drive of such parodies to poke fun at the New Woman, cartoons like this one inadvertently reveal deep-seated anxieties about this figure and her transgressive potential. In actuality, the top hat at the heart of this cartoon offered men important advantages over women, including an increase in height of approximately 6-7 inches, as well as a private storage space—a corollary to pockets—that could house everything from cigars to letters to puddings (Charles Dickens humorously describes the latter usage in “Night Walks”).(1) Read in this light, the New Woman’s appropriation of the top hat signals a troubling challenge to gender norms; in using the top hat, the New Woman not only raises questions about her own gender role, but also simultaneously emasculates men—a common pattern in such parodies that is often depicted through imagery of a statuesque New Woman physically dwarfing her much smaller male counterpart. In this case, though, she does so by gaining access to supposedly private male space and thereby metaphorically taking men down in size. The cartoon thus raises the question of whether the New Woman’s adoption of the features of male dress might also lead to the appropriation of the masculine privileges the top hat represents, including privacy, the right to property ownership, and the posturings of authority and gentility that go along with this element of a gentleman’s dress.

<4>In the pages that follow, I focus on the question of whether changes in women’s dress at the fin de siècle could lead to genuine transformation—including the adoption of masculine privileges and authority. My focus, however, is on a more subtle act of sartorial appropriation than the example given above: the use of integrated pockets that emulated male dress. While this may seem like an inconsequential feature of women’s dress, and while we are more likely to think of bloomers or the divided skirt as the sartorial symbol of the emancipated woman, the rhetoric surrounding pockets and their placement and use suggests that they offer a telling measure of women’s status in relation to gender at the fin de siècle. As Barbara Burman has persuasively argued, pockets function as “a conduit towards the body,” one that “signals the extent to which the clothing of men and women is open or closed to the outside world. It indicates gender by the degree to which the body beneath can explicitly draw attention to itself, and thus how much that body can inhabit, confront or command the social world” (460). The integrated pockets that women adopted at the fin de siècle did garner notice as they helped women negotiate a new relationship to the public world.

<5>In their work on women and material culture, Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin argue that “Not only do objects, like dresses and gloves, participate in the formation of identities and the constitution of embodied subjectivities; subjects can endow objects with subjectivity, and furthermore, objects can act with a kind of agency we tend to think should be reserved for human subjects” (2). Pockets are fascinating as everyday objects precisely because of their flexibility and because of their association with agency through the gendered privilege of carrying money or property. Because the placement and use of pockets on women’s dress shifted at the end of the nineteenth century, they serve as a fascinating site for examining the expectations of women and the fears of both men and women regarding shifting gender roles at the fin de siècle.

<6>We need only look to late nineteenth-century proponents of dress reform for evidence of the foundational role dress might play in bringing about equality for women. This argument is neatly encapsulated in an 1888 piece from The Rational Dress Society Gazette:

…Dress Reform is fundamental, and must advance before other movements

prosper. Financial independence is the basis of woman’s as well as man’s liberty.

That she cannot gain while weakening and obstructing her body by a dress ‘à la

mode.’ Opening avocations are useless to her. Asking rights and equality is

simply absurd. Of all the reforms aiming at woman’s enfranchisement, none is

more pertinent than dress reform. (Rational Dress Association, No. 2)

The claim here that dress reform must proceed before all other advancements for women may prosper points to the crucial role that dress plays. Indeed, the rhetoric of the cartoon depicting a New Woman with a hat and the discourses surrounding dress reform both evoke the potentially magical transformations associated with the new modes of rational dress. While the cartoon subtly reminds viewers of the magician’s trick of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, an example from the Rational Dress Association’s exhibition makes this association with magical transformation more concrete. At the exhibition, the organizers sponsored a competition, offering a monetary reward to the designer who created a dress which met five requirements ranging from freedom of movement to beauty and grace. The winning entry was a hybrid costume that one visitor describes as follows:

. . . the best thing shown by this exhibition . . . a ladies’ travelling dress, which

can be converted into a really handsome dinner dress in five minutes—

without help—and the whole of which can be stowed away in a flat box ten

inches long . . . I saw the magic change wrought, and should believe that for

travelling brides and ladies with scant luggage the invention is a thing to be

worshipped. (Rational Dress Association, No. 2)

Allowing women simultaneously to be genteel and inconspicuous but also mobile, this hybrid dress represents the possibility that through a quick change of clothing, women might gain the freedom to move and to travel. This idea reinforces the notion that wearing rational dress does not represent a superficial change, but rather, that it has the potential to enact genuine transformation.

<7>Following this line of reasoning, this article analyzes rational dress of the 1880s and 1890s, when pockets were integrated into women’s clothing after the fashion of men’s clothes instead of being tied on as separate articles. Drawing on fictional representations and on cartoons from the famously satirical magazine, Punch, or the London Charivari, I argue that these new pockets represented a significant sartorial change that was threatening not only because it relied on the appropriation of elements of male dress, but also because it prefigured more significant freedoms for women seeking access to financial independence, privacy, mobility, and sexual freedom, as well as the self-assurance that would accompany these changes.

Women’s Pockets at the Fin de Siècle

<8>Pockets served a variety of important functions for Victorian men, and the New Woman drew on these aspects in her appropriation of the more masculine form. In tracing Victorian debates about the proper form and placement of pockets in the Victorian period, Christopher Todd Matthews has argued that pockets helped divide men and women symbolically and functionally, and that “this presumed distinction organized culture-wide discussions of sexual difference and its relation to nature, money, and mobility. The question of who gets pockets and how thereby becomes more than a footnote of fashion history: it becomes part of the broader history of bodies and their gendered meanings in public space” (3-4). The fact that fashion dictates such divisions should not surprise us, according to Anne Hollander in Sex and Suits, since “Male and female clothing, taken together, illustrates what people wish the relation between men and women to be, besides indicating the separate peace each sex is making with fashion or custom at any given time . . . The history of dress . . . has to be perceived as a duet between men and women performing on the same stage” (7). To better understand how the usage of nineteenth-century pockets was coded in gendered terms, I thus turn briefly to a consideration of men’s pockets in representative examples from Victorian novels, which are filled with copious references to this sartorial element.(2)

<9>Just as different types of pockets have specific uses (think of a breast pocket, watch pocket, etc.), Victorian novelists use pockets to multiple ends in their fiction. Burman notes that “the generous allowance of pockets in suits underscores the association of masculine authority with ownership of property” (455). Indeed, several colloquial expressions signify the linkage of pockets with property and money—for example, those who are “in pocket” have money, while those who are “out of pocket” do not—and Victorian novelists often play up this association. In Dickens’s David Copperfield, for instance, the eponymous hero relishes the experience of having spending money for the first time when he reflects that “it was a great thing to walk home with six or seven shillings in my pocket, looking into the shops and thinking what such a sum would buy” (Dickens 173). Charlotte Brontë explicitly links financial wealth and masculine privilege in Jane Eyre when Mr. Rochester explains to Jane how his French mistress, Céline Varens, “charmed my English gold out of my British breeches’ pocket” (italics mine, 184). For the British gentleman, to be in possession of money in one’s pocket is to have freedom and power. By contrast, Victorian novels are populated by unfortunate men like Wilkie Collin’s character in The Moonstone for whom “The more money he had, the more he wanted; there was a hole in Mr. Franklin’s pocket that nothing would sew up” (29).

<10>In addition to holding money, pockets also perform the important function of housing private, and sometimes very personal, possessions. Pockets offered a degree of privacy that was unusual because “In the days when people often shared bedrooms and household furniture, a pocket was sometimes the only private, safe place for small personal possessions” (“A History of Pockets”). In scores of instances across Victorian novels, men’s pockets house private letters to be read or revealed at strategic moments in the novels’ plots. Additionally, they often house tokens of romantic affection. In Anthony Trollope’s Phineas Finn, the titular character reaches “his hand up to his breastcoat pocket, and felt that Mary’s letter,—her precious letter,—was there safe” (Trollope, ch. 69), while in another scene “the ringlet was cut and in his pocket before she was ready with her resistance” (Trollope, ch. 2). Phillip Wakem in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss likewise carries a token of his beloved, which Maggie Tulliver discovers when he “drew a large miniature-case from his pocket, and opened it. Maggie saw her old self leaning on a table, with her black locks hanging down behind her ears, looking into space, with strange, dreamy eyes” (Eliot 312).

<11>In addition to private correspondence and sentimental keepsakes, men’s pockets hide more subversive secrets as well. In Dickens’s novels, Mrs. Snagsby in Bleak House spies on her husband through “nocturnal examinations of Mr. Snagsby’s pockets” (378), while in Great Expectations Pip carries a secret stash to the convict on the marshes—his pockets filled with brandy, a pork pie, and a file (15-16). In Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret, Robert Audley keeps a memorandum book in his pocket, wherein he records the details of his investigations, which ultimately allow him to unravel the secrets of Lady Audley’s past. Like the top hat with which we started, men’s pockets in Victorian novels allow for the transport, safekeeping, and concealment of important items, from money to letters to manuscripts to keys.

<12>Yet for all their functionality, pockets also serve an important symbolic role in Victorian novels since “the articulation and form of the male body is emphasized by disposition of hands in pockets” (Burman 461), making this a gesture that imbues a man with dominance and power.(3) In Barchester Towers, Trollope imagines an Earl in his library “preparing his thunder for successful rivals, standing like a British peer with his back to the sea-coal fire, and his hands in his breeches pockets—how his fine eye was lit up with anger, and his forehead gleamed with patriotism” (7). Similarly, this gesture is associated with Mr. Osborne’s dominance as his family’s “dark leader” in William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair as “the head of the family thrust his hands into the great tail-pockets of his great blue coat with brass buttons, and without waiting for a further announcement strode downstairs alone, scowling over his shoulder at the four females” (139). Thackeray’s repetition of “great” in association with pockets emphasizes how Mr. Osborne is made more imposing by this gesture.

<13>In other cases, the posture of standing or walking with one’s hands in one’s pockets evokes a male character’s sense of self assurance, ease, or self-reflection. When Esther observes Mr. Jarndyce in Bleak House, she notes that this gesture alone enables him to ward off the troublesome east wind and restore his sense of ease and equilibrium. She explains:

He began to rub his head again and to hint that he felt the wind. But it was a

delightful instance of his kindness towards me that whether he rubbed his head, or

walked about, or did both, his face was sure to recover its benignant expression as

it looked at mine; and he was sure to turn comfortable again and put his hands in

his pockets and stretch out his legs. (Dickens 122)

Here, the gesture is associated with relaxation and a return to comfort and ease. In a related example, in Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, Sergeant Cuff engages in this trademark action whenever “his mind was hard at work”; at such moments, he stands “with his hands in his pockets, looking out, and whistling the tune of ‘The Last Rose of Summer’ softly to himself” (115). For both male characters, the ritual of putting one’s hands in one’s pockets has a stabilizing and calming effect.

<14>These examples from Victorian novels reveal the significance of pockets for men and begin to offer some insight into why the integration of pockets into rational dress costumes at the fin de siècle might matter to the New Woman. Prior to the nineteenth century, women in Britain wore tie-on pockets that consisted of pouches worn external to the body underneath a woman’s skirts and petticoats, which could be accessed through side seams in the petticoats or by raising the skirts.(4) These pockets were large—typically 27-30 centimeters in length—and as such (Fennetaux 315), they could house a wide variety of objects: from articles for personal hygiene including handkerchiefs, simple cosmetics, and pocket combs and mirrors; to sewing implements including scissors, thread, pins, and thimbles; to edible items including bonbons, medicines, and nutmeg (and accompanying graters); to valued possessions including jewelry or prayer books (Burman and Denbo 24). Although such pockets went out of fashion after the eighteenth century when the silhouette of women’s clothing changed, recent research suggests they continued to be used into the nineteenth century, probably because of their practicality (Burman and Denbo 19-20, 35).(5) However, by the mid-nineteenth century some garments began to include integrated pockets that were sewn in after the fashion of men’s clothing rather than tied on as separate articles. As women’s fashions became more tailored and form fitting at the end of the century, such integrated pockets gradually became the norm.

<15>Research on women’s tie-on pockets has examined the complex ways in which they are linked to issues of gender and sexuality. Ariane Fennetaux asserts that tie-on pockets signaled a woman’s domestic role by virtue of their nature—they were handmade and often embroidered with flowers or initials, and they typically contained implements for needlework (308).(6) Yet even as they highlighted a woman’s domestic role, they also pointed in more subversive fashion to a woman’s sexuality. By virtue of their placement and access underneath a woman’s skirts, they functioned as boundary markers that demarcated a line between private and public space, and were therefore symbolic elements in the negotiation of intimate relationships (Fennetaux 321-22). As such, they are often associated with secrets, allowing the wearer to hide her wealth and treasures—such as a clandestine letter or a memento from a suitor—rather than have them on display. Tie-on pockets also symbolically called attention to a woman’s sexuality because of their proximity to the body, their suggestive uterine shape (Burman 452), and the fact that, “when a woman put her hand through slits in her skirt to access her pockets, she signaled almost directly toward her private parts” (Fennetaux 318).(7)

<16>Many of these associations with sexuality linger on as pockets changed over the course of the century since a woman’s waistline was a critical erogenous zone during the Victorian and Edwardian periods (Kortsch 61). As a result, integrated pockets came to embody complex gender associations. The important boundary function ascribed to pockets above may help explain why “Between the 1870s and 1890s there was a kind of crisis over the position and number of women’s pockets, which attracted the attention of fashion journalists” (Burman 453). The advent of the fashion of visible pockets at the fin de siècle “generated a spate of fussy, ornate and awkwardly situated pockets which were emphatically without much practical function beyond the carrying of handkerchiefs, themselves the subject of discussion in fashion journalism of the day” (Burman 463). While Burman explains that these awkwardly small pockets were emblematic of the restrictions women faced with respect to a lack of financial autonomy and property rights at the end of the century (458-9), I would argue that it is precisely the lack of functionality that signals the extent to which these pockets represented a disruptive social force. They reveal that the New Woman was beginning to be successful in usurping the all-important symbolic role made possible by the gesture of hands in pockets, and that she threatened to gain the corollary privileges of financial autonomy, privacy, mobility, and sexual freedom. As such, the pocketed woman became a subject of controversy and parody in the periodical press.

<17>An 1894 issue of The Graphic makes clear the extent to which the structure and placement of women’s pockets became an important focal point in discussions of women’s dress at the fin de siècle. The author writes:

The inevitable feminine coat and skirt nauseates the eye just now . . . I observe

now that the ladies, like men, walk with hands in their pockets . . . The pockets of

the ‘New Woman,’ admirably useful as they are, seem likely to prove her new

fetish, to stand her instead of blushes and shyness and embarrassment, for who

can be any of these things while she stands with her hands in her pockets?

(“Place aux Dames” 15)

The New Woman’s stance, made possible by the materiality of what is likely a “tailor-made,” an outfit Christine Bayles Kortsch calls “a practical daytime uniform for the thousands of women now entering newly emerging or once male-dominated occupations” (65), is suggestive of the way that pockets function on both a literal and a symbolic level.(8) The Graphic calls attention to their role both as an “admirably useful” technology that allows women to behave like men, presumably as consumers, by providing a private place to hold money and other valuables. Yet pockets are also explicitly linked to a new persona for women—one characterized by self-possession instead of the “blushes and shyness and embarrassment” typically associated with conventional feminine modesty and self-effacement. This quotation thus hints at the transgressive potential associated with women’s pockets and the extent to which rational dress—and the posturing that went along with it—posed a threat to gender norms. As Sally Ledger asserts, “Gender was an unstable category at the fin de siècle, and it was the force of gender as a site of conflict which drew such virulent attacks upon the figure of the New Woman” (2). In the following pages, I examine a series of such attacks in Punch cartoons—some more lighthearted than others—that reveal the subtle role that integrated pockets play in positioning the New Woman as a dangerous threshold figure.

Punch Parodies and Subversive Pockets

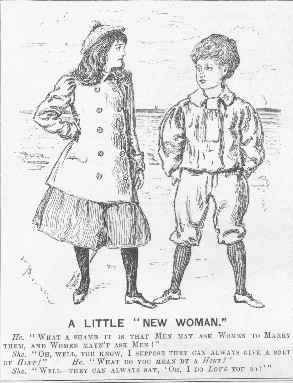

<18>In the first two cartoons under discussion, “We’ve Not Come to that Yet” (Figure 2) and “A Little ‘New Woman’” (Figure 3), we witness the association of pocketed New Women with an emerging sense of power and a drive for emancipation, particularly as it relates to courtship and marriage. Both cartoons were published in 1894, on the heels of the Married Women’s Property Act of 1893, the culmination of a series of legislative acts that gradually granted women control over their own property in marriage, ultimately putting married and unmarried women on equal footing in this respect. These cartoons reveal anxieties about the implications of the new legislation in their depiction of New Women who assert novel rights and freedoms within the context of courtship and marriage. Although neither of the young female figures caricatured has her hands in her pockets, the jackets they wear possess patch pockets, and by virtue of their dress, they both gain an air of authority in contrast to the more effeminate posturing of the men opposite them.

<19>In “We’ve Not Come to That Yet,” the cartoon emphasizes an inversion of roles within marriage, with the caption parodying the man’s subservient position in relation to his wife. As it jokes about the possibility that a husband might adopt his wife’s name after marriage, the cartoon betrays a sense of unease about male and female identity and roles within marriage and perhaps speaks to the ways in which the most recent legislation further disrupts the “natural” order of things with respect to gender roles. While the title of the cartoon reassures the audience that the catastrophic upheaval it imagines is off in the future, the second cartoon suggests that the underpinnings for such dramatic change are indeed already underfoot.

<20> “A Little ‘New Woman’” depicts a young girl in rational dress who challenges the gender politics of Victorian marriage by suggesting young women—and perhaps even girls—should demonstrate initiative in matters of courtship. Despite being “Little,” this New Woman is depicted in an assertive posture with her hand on her hip, tellingly just above her pocket. Writing in defense of rational dress for children in late nineteenth century, Constance Wilde argues that “this change is not a change of form only, in which women’s dress has shared, but a change of feeling . . . The greater number of children are undoubtedly dressed more simply, more rationally, more like human sentient beings, less like wooden dolls, or dummies to wear the freaks of fancy dictated by dressmakers” (413). In equating the new dress for children with a change not just in “form,” but also in “feeling,” Wilde insists that rational dress invites more than a superficial transformation. Indeed, the little “New Woman” here proves herself a “sentient being” and not a mere doll as she confidently contradicts her young companion, insisting upon the New Woman’s prerogative to speak frankly and to express her feelings honestly in matters of love and marriage. While her age makes her a less threatening representation of a woman’s autonomous identity than the New Woman figured in “We’ve Not Come to That Yet,” “A Little ‘New Woman’” is suggestive of how a new generation of girls are adopting progressive views that might lead to feminist practices like retaining control not only over property after marriage, but also over one’s name—and by extension, one’s independent identity.

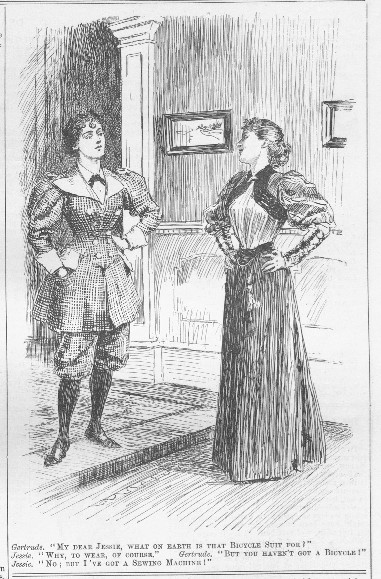

<21>Similar feminist impulses are evident in an 1895 cartoon depicting a woman in a bicycle suit (Figure 4), which illustrates the association of pockets with the New Woman’s desire for meaningful occupation, the drive for physical mobility and adventure, and her ability to craft her own identity. In this image, a woman in rational dress with one hand in her coat pocket stands in opposition to another woman who is dressed conventionally, and their posture of standing with their hands on the hips stages a friendly confrontation. The woman on the right-hand side wears keys that hang from her waist, symbolically weighing her down (a trope that was common in parodies of domestic women),(9) whereas the New Woman is boldly transgressive as she stands with her hand in her pocket and projects a sense of confident pride in her own initiative and industriousness. Her power stems not only from the fact that she is wearing rational dress, but also from the fact that it is handmade; in creating it, she has clearly re-shaped herself and her identity in a way that surprises her companion. Her use of a conventional domestic object—a sewing machine—to create her own costume rather than to beautify her home or her person hints at a desire for meaningful and purposeful work that extends beyond the domestic realm.

<22>The fact that this New Woman lacks the bicycle to go along with the costume renders her bicycle suit an aesthetic statement rather than a utilitarian investment, one that hints at her threshold status as a figure who might indeed become ever more transgressive once she acquires the additional freedom and physical mobility that a bicycle could provide. Indeed, although the cartoon questions whether rational dress has a legitimate function, by merely wearing the suit, the woman pictured here lays claim to the freedom to escape the domestic realm through physical activity, a drive Patricia Marks explicitly links to the New Woman’s dress: “Freed from heavy, clinging skirts and constrictive whalebone undervests and wearing stout boots instead of slippers, the New Woman increased her physical movement both in and out of the home” (148).

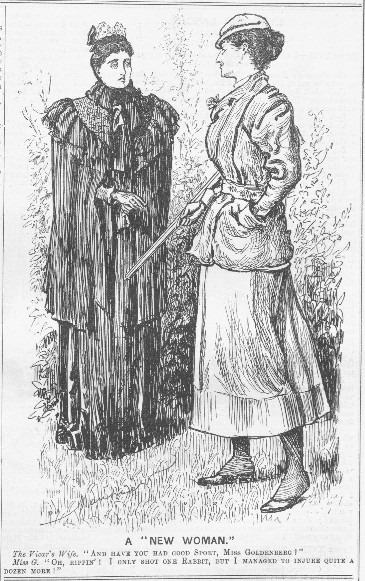

<23>Another 1894 image of an active woman with her hands in her pockets, “A ‘New Woman’” (Figure 5), reinforces the idea that a change in dress can lead to troubling transformations in a similar parody of a sporting woman who is appropriately dressed but inept at her sport. Wearing rational dress and standing at ease with one hand in the pocket of her jacket and the other hand supporting her rifle, the New Woman is dramatically contrasted to the vicar’s wife with whom she speaks, who is physically immobilized by heavy clothes that appear to weigh her down, making her head and hands appear absurdly tiny and fragile. As Ariel Beaujot has argued, images of fragile women such as the vicar’s wife “helped demonstrate to women that they must not use their hands for work, or even for holding objects of women’s apparel too firmly, if they were to have the perfect hand. The limp hand gestures reminded onlookers of the female passivity and weakness apparently engaged in by noble women” (40-41). In contrast to such weakness and passivity, the active women pictured in the two cartoons above use their hands for more deliberate purposes as they infringe both on male prerogatives of dress—by adopting the casual stance of standing with hands in pockets—and on male leisure pursuits such as cycling and hunting. These transgressive women become the subject of parody because they suggest that the imitation of male dress, including integrated pockets, is merely the first step to more threatening forms of emulation.

<24>Such emulation is also evident in the final cartoons I will highlight, which depict New Women with their hands in their pockets who do more than merely look the part; in these cartoons, the women have crossed over a threshold of simple imitation to act—and not merely look—like men. In so doing, they move from being a source of comedy and derision to being a threat to be regarded more seriously. In the first cartoon published in 1891, the emphatic title—“The Sterner Sex!” (Figure 6)—invites viewers to consider the way the New Woman inverts gender stereotypes. Indeed, the woman pictured wears a man’s hat and coat that is borrowed from a young man named Fred, and with the exception of her skirt, she adopts a very masculine persona. By doing so, she disrupts gender norms and reinforces anxieties about the inversion of gender roles brought on by rational dress, as her companion humorously notes that donning a man’s dress makes her look “so effeminate!”

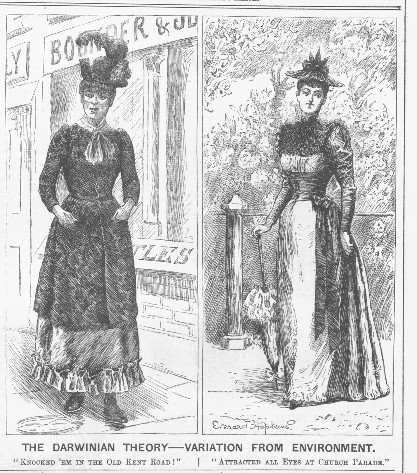

<25>In the second cartoon from 1892, “The Darwinian Theory—Variation from Environment” (Figure 7), the pose of walking with hands in one’s pockets is linked to the New Woman’s freedom as a consumer and as a sexual agent. The former association is created by the setting, which depicts the New Woman on a London street passing in front of a shop window that appears to read “Bounder & Sons Textiles.” The allusion to a bounder connects the New Woman and her fashions (this is after all, a shop selling articles of clothing) to dishonor of a specific kind, namely, fortune seeking and a desire to rise above one’s “proper” station. This idea is reinforced by the caption accompanying the New Woman’s image, “Knocked ‘em in the old Kent Road!,” which derives from a famous music hall song that details the story of a dubious inheritance. In the song, a woman inherits a horse-drawn carriage and a decrepit donkey from a rich uncle, and proceeds to put on airs as she waves and bows to her neighbors, who in turn greet her with good-humored derision. These associations, and the connotation of “knocked ‘em” as slang for made them stare, suggest the New Woman pictured here—like her counterpart in the music hall song—is a source of public spectacle. In opposition to her mirror image—the refined lady in the opposite panel who fits beautifully into the idyllic country setting and attracts admiration—the setting in which we find the New Woman is depicted as contrived and unnatural, as the site of her degeneration.

<26>Such degeneration is also alluded to through the cartoon’s emphasis on the contrast between the two women and the ways in which dress helps to demarcate these distinctions. Burman notes that the absence of visible pockets in women’s dress prior to the mid-nineteenth century helped to isolate and protect women in spatial terms:

The respectable female body in the nineteenth century is shown as shielded and closed off by its clothing, its power in the social world thus formally inaccessible and unknowable. In a self-fulfilling embodiment of gender difference, women’s delineation and management of their own bodies in social space was limited by their lack of opportunity to touch their own bodies, by proxy, through their pockets. Instead, their hands made other gestures through the medium of dress by smoothing or arranging their clothes or through elegant turns or tasks such as pouring tea, holding fans, sewing or knitting. (460)

The contrast represented in this cartoon beautifully illustrates Burman’s point here about the ways in which women’s clothing limited and shielded women. The fashionable woman depicted here is “closed off,” and the hand that rests on her parasol is reflective of the type of artful, contrived gestures that were associated with idealized femininity.(10) By contrast, the New Woman walks with the more masculine gesture of putting her hands in her pockets, and the fact that we cannot see her hands calls attention to what is underneath her skirts, and possibly to the question of what they might be doing there. Other details in the cartoon reinforce these associations with the sexual body, including the woman’s darkened visage, which contrasts dramatically with her counterpart’s porcelain face and suggests the extent to which the pocketed woman—rather than being “closed off” and “inaccessible”—is vulnerable to outside forces, in this case, the dirt and soot of the city streets. Her dark face suggests both her contamination by urban living and her subsequent racialization as “other,” which is emphasized in the parody by the disconnect between her representation and that of the ideal woman.

<27>The distance between the ideal woman and her counterpart also underscores the concept of degeneration implied in the cartoon’s title, which is often tied to sexuality in fin de siècle literature. This distance is rendered in large part by the differences between concealed versus visible pockets, which may represent “the perceived binary division between the controlled, clean and concealed body of the respectable woman and the uncontrolled, dangerous and more visible body of the working or fallen woman. When open, the visible pocket transgresses or breaches the boundary between the body and the social world” (Burman 463). The contrast between the two women’s gestures—one holding a parasol and one holding her hands in her pockets—aligns the former with sexual purity and the latter with sexual degeneration, both through the image’s subtle allusion to masturbation and to its more obvious allusions to prostitution. The New Woman is linked to the latter as she strolls down an urban thoroughfare and walks over a sewer cover on the Old Kent Road, a geographical locale that marked the London city limits and was historically associated with criminality. Finally, the cartoon’s title implies that urban environments and the clothing in which New Women navigate them—including the pockets that enable them to act like men by gaining access to money, privacy, mobility, and power—invite a dangerous transformation and lead inevitably to degeneration.

***

<28>By portraying the New Woman in a parodic light, these and other cartoons from Punch figuratively pick the New Woman’s pocket by shining a spotlight on her mode of dress and by undermining the import of her outward, sartorial change. They reinforce an assumption that such a change is frivolous and insignificant, thereby attempting to defuse the threat that an external change might also signal a transformation that is not so superficial, the ability to adopt the privileges and power that go along with having accessible pockets.

<29>To close, I refer to another New Woman, Thomas’s Hardy’s Sue Bridehead, who dons a man’s suit in Jude the Obscure (1895) and rejects her own garments as “only a woman’s clothes—sexless cloth and linen!” (Hardy 178). Despite Sue’s dismissiveness about the importance of her clothes, my focus on women’s pockets begins to reveal that the material culture associated with the New Woman, especially surrounding dress reform and the structure and placement of pockets, is far from insignificant; rather, it had meaningful ramifications for women’s emancipation at the fin de siècle. According to one dress reform advocate writing in 1894, “The woman question, in all its phases, must ever resolve itself into a problem of dress. For are not all ‘individuality, distinctions, and social polity’ given to women by clothes?” (“Rational Dress for Cyclists” 3). Rational dress, including but not limited to the integration of women’s pockets, played a substantial role in shaping female identity at the fin de siècle as it raised troubling questions about what could happen once this threshold figure—the pocketed woman—stepped beyond the boundaries of the home, out into the streets, and past the city limits.