<1>While visiting England in 1827, German Prince Pückler-Muskau made this comment in a letter:

After Almack’s, there is no way of approaching an English lady so good as politics. There has nothing to be heard lately, whether at dinner or at the opera, nay even at balls, but Canning and Wellington from every pretty mouth; nay, Lord E— complained that his wife disturbed him with politics at night. She frightened him by suddenly calling out in her sleep, “Will the Premier stand or fall?”(1)

For early nineteenth-century people, Almack’s—a club on St. James’s Street and the site for the famous Wednesday balls organized by a small coterie of upper-class ladies—was another name for fashion: it stood for the “seventh heaven of the fashionable world” in Captain Gronow’s words.( 2) What Pückler-Muskau voices here, then, is no more and no less than a common nineteenth-century notion, namely that fashion leading and fashion following could be a major means for women to get involved in the public sphere, say, to discuss politics—a conventionally unfeminine topic. In other words, there was a rule of fashion that allowed women to rewrite from time to time the longstanding norms of domesticity and find their way into public life in unexpected ways. It is this fashionable rule, I argue, that we must highlight for a fuller and richer history of nineteenth-century British women and especially of the elite group.

<2>Scholars of nineteenth-century women and gender are gradually moving away from a middle-class centered, separate-sphere informed historiography that highlights the figure of the domestic woman. While there is far from enough work on addressing what David Cannadine terms the “urgent need for more history of upper-class women,” recent scholarship has not only revised and challenged the separate-sphere model but also opened up ways of examining conventionally trivialized areas: consumerism, fashions, life styles and polite sociability, to name but a few.(3) Yet often times, fashion in existing scholarship is simply understood as stylistic change in dressing and living, i.e. as part of consumerism and consumption. Frequently missing is the strong nineteenth-century sense of fashion as what rules Society (also called fashionable society, the beau monde, the ton, the world of fashion, or simply the World)—that special arena or system for norm-producing social activities, one that “was vastly expanded and infused with new authority in the second quarter of the century.”(4)

<3>Meanwhile, studies of nineteenth-century aristocratic women have also largely ignored fashion as such.( 5) Scholarship in this respect usually presents two major views on aristocratic women’s societal roles. One goes that noble ladies achieved political goals and enjoyed public privileges mainly due to their class advantages: In tune with the dynastic or familial nature of aristocratic society, women in the noble circles served as second persons of aristocratic men to manage estates, dispose patronage, and even exercise political influence in party organizations and government.(6) Another view complicates the former notion by highlighting the gender disadvantages of aristocratic women. While aristocratic women shared the “power and prerogatives of men in their class,” as Peter Mandler frames it, they—because of their subordinated positions—were the first to break with the traditional structures that came increasingly “under democratic or meritocratic pressure”; and “in fashioning for themselves alternative public roles[…] aristocratic women joined with middle-class women and made a signal contribution to the construction of new, liberal forms of political subjectivity in the early nineteenth century.”( 7) How was the break made? Where did the joining of forces happen? Could fashionable society be a major site for that?

<4>These questions have not caught much attention not the least because the tradition of trivializing and feminizing fashion in its common sense is long standing. As David Kuchta traces in his 2002 book, a prominent theme in British political culture from the late seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries was the Great Masculine Renunciation: by renouncing splendor and luxury, men claimed politics as a masculine field of simplicity, probity and industry, and at the same time excluded women from it by “naturalizing them as frivolous slaves to fashion.”( 8) Partly due to the profound political implication of the feminization of fashion, early feminists such as Mary Wollstonecraft must not only denounce fashion but also denaturalize its association with women in order to assert women’s rights to politics: “fashion….is but a badge of slavery, [and yet] the attention to dress […] which has been thought a sexual propensity, I think natural to mankind.”( 9) When Wollstonecraft called for a “revolution in female manners,” she appropriated the idea of masculine renunciation for female use: by giving up fashion and “reforming themselves,” she argued, women could “reform the world.”(10) This feminist urge to depreciate fashion survives even till today. As the cultural critic Joanne Finkelstein puts it, “feminist readings of fashion have often portrayed it as a kind of conspiracy to distract women from the real affairs of society, namely economics and politics […and] seen as a device for confining women to an inferior social order.”( 11) Such readings must have been strong enough for Carolyn Beckingham to have raised once again the question Is Fashion a Woman’s Right? in 2005.(12)

<5>Just as feminist comprehension affirms the chasm between fashion and the public sphere while lambasting the constructed nature of their relationship, another line of thinking does the same by simply reversing cause and effect: because women are shut out from the public sphere, from the more “valuable pursuits” of preaching, litigation, diplomatic negotiations and so on, women have to go to, or are allowable to use, fashion for personal distinction, social acceptance, and vicarious consumption.( 13) Whichever direction they go, these lines of conceptualizing the relationships among women, fashion and the public sphere do not allow the possibility that fashion might just be a means for women to materialize their public roles; nor do they provide an adequate recognition of the nuanced tie between fashion, gender and class. This essay hopes to address the inadequacy by tracing the emergence of the chaperone of fashion and the fashionable lady patroness as distinctive social identities in the early nineteenth century. It argues that the rule of fashion played a significant role in enabling aristocratic women to negotiate dynamically between their class advantages and gender disadvantages for the realization of public functions in unexpected ways.

The Rule of Fashion

<6>By the early nineteenth century, various observers of English society had noticed a new force that was shaping British life in a more and more palpable way, and that force was simply but appropriately termed fashion. If Thomas Gillet, a fashionable writer in the early decades, felt like writing about “the tyrant that most widely reigns” in 1819, Letitia Landon, the poet, was still lamenting “Fashion, that tyrant” in 1829.( 14) While in 1832 the English lady Harriet Pigott framed Britons as “the greatest slaves” to fashion, the German prince Pückler-Muskau observed similarly in 1833: “Where fashion speaks, the free Englishman is a slave.”(15) Another foreign observer Flora Tristan made a similar comment in 1842:

The Londoner has no opinions or tastes of his own; his opinions are those of the fashionable majority, his tastes whatever fashion decrees. This subservience to fashion is general throughout the land; there is no other country in Europe where fashion, etiquette and prejudice exert such monstrous tyranny.( 16)

The French feminist and socialist’s seeming generalization was only confirmed by the author of The Handbook of the Man of Fashion who wrote in 1846: “[fashion] is, in and for itself, a thing so greatly valued and craved by every class of persons, that the mode of winning it becomes an interesting consideration to all men.”(17)

<7>What was, then, this thing “craved by every class of persons”? What constituted “this entirely new power [that] was placed on the throne, as supreme and absolute sovereign”?( 18) Nineteenth-century Britons have left us with numerous speculations about the rule of fashion.

<8>A chief way in which Victorians conceptualized fashion was to connect it with magical power, as was expressed by a Court Journal author:

Enchanting Fashion! Tell me which

Art thou, a will-o’-wisp, or witch,

Or one of those delightful things

That poets deck with stars and wings

Sent down with brilliant spell and wand,

To turn the earth to fairy land.(19)

For the anonymous poet and many of his contemporaries, fashion comes close to what Gilles Lipovesky has recently termed the “system of aesthetic fantasy.”(20) Such words as “witch,” “spell,” and “fairy land” vividly convey the idea that fashion enchants by mythic powers; and like poetic art, it is capable of rendering plain earth into a fantastic world. In this sense, fashion could serve as a tool for what Walter Benjamin would have taken to be the “reenchantment of the social world” in the industrial age.( 21) But instead of viewing this enchantment as a source of false consciousness—as it would have been to Adorno and Horkheimer—some nineteenth-century Britons accepted mysterious fashion pragmatically as an inevitable regulator of one’s views and conduct.(22) As is put by the anonymous author of The Handbook of the Man of Fashion:

Fashion, like Sir Fopling Flutter, is a thing “not to be comprehended in a few words.” Its empire is one of the darkest mysteries of life. [. . .] We should accept Fashion, in the way that Sir Robert Peel accepted the Reform Bill, as a fact, —an actual and settled circumstance, in reference to which our views and conduct must be regulated.( 23)

This author’s empiricism on fashion was certainly not his alone.

<9>Another major strand in nineteenth-century people’s conceptualization of fashion lay in their realization of its self-constitutive nature as a form of power. An example of which can be found in an 1829 Court Journal article:

It is certainly not without reason that we sometimes complain of this power, called Fashion, being somewhat arbitrary in the exercise of its self-constituted authority, the control it arrogates, and the capricious forms it assumes.( 24)

Here, the anonymous author clearly anticipates what Roland Barthes later would frame as the self-reflexivity of fashion: it always refers back to itself as the only source of authority.( 25) This self-reflexivity was expressed more clearly by the German prince Pückler-Muskau, according to whom fashion in England was not “influenced by rank, still less by riches but [found] the possibility of its maintenance only in this national foible [of believing in fashion].”(26)

<10>Yet another strand in nineteenth-century people’s thinking of fashion manifested in their identification of its pursuit of novelty. An 1823 New Monthly Magazine author, for instance compared fashion to protean figures in Greek mythology, albeit in a very critical tone:

To catch “the Cynthia of the minute,”—to depict the ever-shifting Proteus universally worshipped by the most ardent of votaries, to define with fidelity its multiform transmutations, and the flickering hues that sparkle around the idol, coming and going like the ebb and flow of the ocean, would be a vain task for pen and pencil united.( 27)

Despite this commentator’s negative view of fashion as an “idol” of “fools,” he shared with his contemporaries, not just a sense of its seductiveness—it attracted “the most ardent of votaries”—but also the insight that constant and uncertain change was fashion’s major way to function. Even the ocean metaphor was a common device. Another person, for example, would write of the “shifting sandbank” of fashion which maintained its interest by the “incessant production of new varieties.”( 28) About a hundred and fifty years later, scholars would take this “incessant production of new varieties” as a fundamental built-in mechanism of “hot societies” that “willingly accept, indeed encourage, the radical changes that follow from deliberate human effort and the effect of anonymous social forces.”( 29)

<11>Still another major thread of Victorians’ conceptualization of fashion was their recognition of its capacity to synthesize contradictory trends and impulses. As put by William Hazlittt, “FASHION is an odd jumble of contradictions, of sympathies and antipathies.”(30) In this sense, fashion resembles Walter Benjamin’s “dialectical image” in its dynamic aligning of antithetical elements such as the artistic and the technological, the mythical and the historical, the old and the new.(31) If for Hazlitt, fashion is nothing but “the prevailing distinction of the moment,” there is, for Benjamin, a“darkness” to this moment which is embedded in the “dream consciousness of the collective.”( 32)

<12>While the four major strands do not exhaust nineteenth-century people’s conceptualization of fashion, they are enough to demonstrate that what they had in mind was a new micro-political form of power—one that was neither completely an ideological ruse of the old declining nobility deployed to affirm the rule of aristocracy, nor completely a democratizing force exerted by the rising bourgeoisie. Instead, fashion integrated the interests of both in a socially unifying system of representation. By cutting across old land, birth and rank, as well as new title, wealth, and intelligence, fashion rendered it possible for them to transform subtly into each other in a fresh realm: the world of fashion that was increasingly shaped by novel norms of distinction—distinction one had to achieve following the sole rule of fashion. It was in this strive for fashion-driven distinction that the new roles of the chaperone of fashion and the fashionable lady patroness emerged as distinctive identities among elite women.

The Chaperone of Fashion

<13>The chaperone or the female leader of fashion occupied

the highest position in the World, moving among the “August, the

Illustrious, the Distinguished, and the Select” Circles of high

life.(33) Also called the Merveilleuse,

especially in the early two decades, she embodied the very “first

class” of fashion and did the job of ruling the beau monde.(34)

Although a leader of fashion usually came from the upper layers of

society, class status did not necessarily confer, and was even not

absolutely indispensable for, the position. In the cross-class

fashionable society, rank, birth, wealth and fortune might all be

necessary for one to achieve leadership, but they were not enough if

a woman did not have other qualities that fashion favored. Chief

among those were sociability, tact and taste.

<14>Sociability largely referred to one’s capacity to mix

frequently in Society. Whether she enjoyed socializing, a

chaperone of fashion had to be familiar with the rules and politics

of Society and participate in its wide range of activities.

When portraying Lady Peel as a leader of fashion in 1845, the Court

Journal particularly pointed out that although her Ladyship

had a “natural taste” for “quietude and retirement” and “every

strong domestic feeling in her heart,” she knew fully well the need

to “mix much in the world.”( 35) It was

exactly this mixing much in the world that secured her the position

as a chaperone of fashion, which in turn did justice to her position

as the wife of the Prime Minister, according to the same

authority. Sociability was fundamental to a leader of

fashion, even though it must be supported by other qualities.

<15>Tact, for instance, was also indispensable. Although there was no settled definition of it, tact was largely understood as the ability to adjust to and make the best use of whatever circumstances presented; it was the capacity to grasp the tone of the day. An 1829 Court Journal author came closest to giving a definition of tact when he wrote about the “quality, which, in the fashionable world, is appreciated above every other—namely, the power of instantaneously seizing the proper tone in all places, at all times, and under all circumstances.”( 36) As such, tact had different expressions in different situations and might pervade “every thought and movement of a real gentlewoman.”(37) It could very well include the “ready wit and great talent in conversation,” qualities which such a great fashion leader as the Duchess of Devonshire was said to possess abundantly.( 38) It might also entail the wisdom and skill to sit one’s guests properly and arrange one’s parties in splendor and brilliance; the highly fashionable Lady Londonderry was regarded as excelling in this aspect: “There are so few persons who so fully understand the duties of hospitality” [. . .] [and] none understand so well how to arrange the intricacies of so weighty affairs” as a fête or other gatherings.( 39) Tact could also cover the ability to please others and make others feel at home; conspicuous figures in the World, such as Lady Palmerston and Lady Grandville, were all remembered to have this capacity.(40) Furthermore, tact suggested the capability of “appearing to possess more power, and even more knowledge,” than one really had, as Princess Lieven did.(41) In short, tact could come out differently on different occasions; but no truly fashionable woman could do without it, just as she must have another quality highly valued in the beau monde: taste.

<16>Like tact, taste was an unstable characteristic that could be associated with different things. For some, it was tied to the art of toilette. A woman who did not follow fashion like a slave but could dress in a way that was “most advantageous to her” was thought to have “the best taste.”( 42) Yet one could equally be considered to have “the most perfect taste” if one was never seen to wear anything that was “in the least degree outré, or liable to criticism,” as was exemplified by the toilette of Lady Palmerston.( 43) Sometimes, good taste might also involved experiments with “little eccentricities” of fashion; the Marchioness of Ailesbury was known for such oddities in her dress and yet still enjoyed a “reputation for beauty and fashion.”(44) Besides toilette, manner was another way to demonstrate one’s taste. It did not really matter what one actually had: amiability or haughtiness, suavity or coldness, severity or playfulness; so long as one’s manner befitted one, it was considered good taste and doted on by fashion: the haughty Lieven and the affable Palmerston figured equally large in fashionable society. Yet another way in which taste manifested itself had neither to do with one’s toilette or manner; it was simply an abstract quality of beauty, elegance, or charm, or rather some unnamable nature that hung over a person and lent a sort of artistic enchantment to the whole atmosphere around her. A woman who had this quality was often awarded with the highest praise of being a real “ornament” to society—ornament not in the sense of being superficial as we tend to understand the word now, but resembling the twentieth-century sociologist George Simmel’s adornment. For Simmel, adornment intensifies and enlarges the sphere of society, adding to its mundane and trivial “precinct of mere necessity” another limitless one exuding the “free and princely character of our being.”( 45) Various chaperones of fashion had been given or strived for this honor of being a mere ornament to society; Lady Ashburton, for instance, succeeded in being an “ornament to Society [ . . .] to perfection,” according to Jane Carlyle’s satirical but also sour-grape account.(46)

<17>Taste, tact and sociality were of course only part of the arts of society that a woman had to possess in order to excel in the profession of fashion. Nonetheless, they were enough to portray a figure different from the cultural ideal of the domestic woman whose major characteristics various nineteenth-century scholars have identified as submissiveness, purity, piety and domesticity with invisibility underwriting them all.(47) Indeed, if the hallmark of the domestic woman was invisibility, she stood in exact contrast to a leader of fashion. If the former “cannot be seen at all” as under the pen of Mary Poovey, the latter made it her first task to see and to be seen at various sites of Society.(48) For example, to be seen regularly in the Opera House with a considerable number of admirers was an important measurement of one’s leading position in the beau monde. When the Court Journal described the Marchioness of Ailesbury as a leader of fashion in 1845, it particularly mentioned that her box was “ever the rendezvous of all our elegants, who come by turns to amuse its fair tenant with the on dits of the day.”(49) The picture here is a far cry from a woman “who fulfils her role by disappearing into the woodwork to watch over the household,” as Nancy Armstrong describes the domestic woman.(50) The chaperone of fashion was much more of an embodiment of what Beth Newman has recently termed “subjects on display” than of the domestic ideal.(51)

<18>The differences between the two figures would suggest that the leader of fashion posed a great challenge to the ideal of domesticity promulgated by the separate-sphere ideology. This was indeed an idea seemingly strengthened by the existence of large quantities of fashionable literature that often portrayed the domestic woman as the heroine and the leader of fashion as the anti-heroine, such as in Mrs. Gore’s Mothers and Daughters (1834); and by the presence of numerous conduct books that frequently deprived the subjectivity of the woman of fashion in order to set up the desirability of the domestic ideal, as argued by Armstrong.(52) Yet the relationship between the domestic ideal and the leader of fashion in the nineteenth century was far from being this simple: one was positive and the other negative. Instead, the two bore a more dynamic relationship both on the level of representation and on the ground of reality.

<19>On the level of representation, there not only existed a considerable amount of literature—such as the highly popular fashion magazines and newspapers like the Court Journal and the Morning Chronicle—that often apparently and affirmatively portrayed the leader of fashion as the center of Society activities and as a desirable ideal for anybody who could afford fashionable life; there were also numerous pieces whose apparent devaluation of the fashionable woman and elevation of the domestic ideal were undercut by complex undercurrents of reverse attitudes. The point can be illustrated by a look at the 1806 La Belle Assemblée series “Letters to a Young Lady: Introductory to a Knowledge of the World.” The series figure two siblings. Eliza and her elder sister have been brought up like twins—with only the difference of a year between them—and educated by their mother, who used to be the “Angel in the House” but has been dead for a while.(53) The two sisters, ever affectionate towards each other, are now separate for the first time as the elder one enters fashionable life in the metropolis while Eliza, stays to take care of their father, an invalid country gentleman. Eliza asks her sister, now a fashionable lady, to write about the world of fashion and in this way to teach her “the science of duty and the arts of life.”(54) While her sister constantly praises Eliza as the better one performing “calm, innocent, and dutiful occupations”—i.e. as another embodiment of the domestic angel—she nonetheless admits to her own susceptibility to the power of fashion and her enjoyment of social calls, balls and parties in the beau monde. What’s more, she gives Eliza immensely-detailed descriptions of her new fashionable activities and encounters, which constitute a great source of delight and knowledge—and a means of education—for the latter. This recount of the series, though brief, should have allowed one to see that these letters—like countless other pieces of advice literature—set up a highly complicated dynamic between the domestic woman and the fashionable lady. First, the two were closely related like two sisters, two cousins, or a mother and her daughters. Second, although the domestic ideal should be continued through generations, each generation has to transform it via the fashionable ideal. Finally, although stemming from the domestic woman, the fashionable ideal nonetheless assumed more importance in shaping current life, which was obviously suggested by the fact that the fashionable lady took the position of a major speaker and a desirable teacher to the domestic woman. Demanded by current exigencies, the fashionable lady rose to transform and meanwhile retained the ideal of the domestic woman.

<20>Such a complex dynamic between the two, as conveyed by the letters, was not ungrounded in the intriguing social vicissitudes in life. Because a chaperone of fashion’s sphere was Society, which was neither public nor private but dynamically intersected with both, a fashion leader did not necessarily dismantle the validity of the public/private division; instead, she simply provided a particularized version of the forms that norm could take in real life. As in the case of Lady Ailesbury, the public/private division was kept in the analogue contemporaries saw between private boxes and private drawing-rooms. The former were private not only because they could be reserved and privately owned for the season but also because they could indeed provide some degree of privacy for the occupants due to the partitions between them and the curtains at the front. Contemporaries indeed had a sense of their private nature, as the fashionable paper The Town made it clear in 1838:

[Opposed] as we are to the unrestraint private intercourse of young ladies and gentlemen, in a moral point of view, yet we confess that we should think it next to sacrilege to break in upon a [couple of] sweethearts’ tête-a-tête in a private box at the theatre.(55)

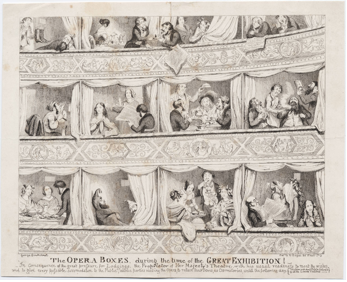

Nonetheless, the privacy was extremely tenable since it not only existed in public but was also largely designed for the purpose of display. George Cruickshank made fun of such tenable privacy as well as the absurdity of people using the opera boxes as temporary dormitories when lodgings were difficult to find during the Great Exhibition ( Fig.1). The illusion of the boxes as private drawing rooms is adeptly revealed by a man’s peeping through a ventilator at the young woman in the next box, by two gentlemen exchanging tea, and by people trying to hide behind and yet look over the curtains. Still, a woman in her box was supposed to behave as she did in her house; only the fact that she acted under the gaze of a public and for that particular purpose rendered the expression of that division much more complicated in life than on the ideological level. This complication, or rather a leader of fashion’s subtle bridging of the gap between a specific norm and the actual form it took can be further illustrated by a leader of fashion’s another act of sociability: the practice of being “at home.”

<21>As an open invitation for fashionable society to crowd onto her staircase, being “at home” allowed a chaperone of fashion both to affirm the ideal of domesticity and to turn it into something else. The affirmation was self-evident: the very naming of the practice suggested that she was not abandoning the domestic sphere: she was “at home” to cultivate friends and to network for the family, which was in tune with conventional gender expectations. Yet, when one, following fashion, brought a huge crowd under one’s roof, domesticity metamorphosed into publicity. In fact, due to the oxymoronic qualities the practice of being “at home” exuded, a woman of fashion could actually make use of it sometimes to break through the confinement of domesticity. An illustrative—though skewed—example of this can be found in the existence of large quantities of literature satirizing the fashionable woman’s running away from her own “at home” to meet with a lover, since, in the gaiety of a large gathering where one guest did not necessarily know another or the hostess, the latter was least likely to be missed! Less exaggerated and more positive portrayal of fashion leaders’ “at home” also abounded. In her letters to the Austrian Prince Metternich, Madame de Lieven frequently mentions how her “drawing-room becomes stifling” during the London season and how it serves as an invaluable site for her to stay in touch with such important figures as the Duke of Wellington, Lord Castlereagh, Lord Liverpool to keep track of European politics; and to have a sense of her own importance in that world.( 56) Likewise, Lady Jersey “made her house the center, of attraction to the then Tory Party”; and Lady Palmerston’s “dinners and receptions kept the [Whig] party together,” according to Lord Lamington.(57) Via fashionable events, these Society leaders broke into the public arena without deserting the domestic sphere.

<22>By converging with and yet diverging from the domestic ideal, the leader of fashion rendered femininity a matter of constant negotiation between long-standing essentialist notions of gender difference and the ever recurring demands of current exigencies. For as scholars have noticed, the public man/private woman division was not a nineteenth-century invention but could date back at least to the fourteenth century.( 58) By the early nineteenth century, reemphasis on this conventional ideology did not just bear on middle-class life, as elaborated by Davidoff and Hall and many others.(59) It also penetrated into upper-class life as various scholars have pointed out.(60) Yet this ideological re-solidification never fully monopolized the landscape of gender as it materialized in daily life. Early nineteenth-century social exigencies—the presence of “social groups faced with the consequence of increased population and urban growth, industrial development and political realignment”—that led to the strengthening and expansion of Society itself also called for new roles that rewrote conventional gender ideologies for new needs.(61) The chaperone of fashion was just one of these roles. Besides her there was another important one: the fashionable patroness.

The Fashionable Patroness

<23>In the Court Journal’s classification of the beau monde, fashionable lady patronesses occupied the “third class” and were said to be “composed of the maiden ladies of rank and widows of small fortunes,” who were employed as “aristocratic ambassadors and ushers of ceremony ” in consideration of “their families and connexions.”( 62) But in fact, those were not the only people who could fill the role of a fashionable patroness. The position could be taken up by anyone who moved around the World and possessed fashionability. Great leaders of fashion would serve as patronesses from time to time, just as fashionable women of less distinguished circles. The fashionable lady patroness differed from the chaperone of fashion in the sense that she did not have the general work of ruling over the World but was assigned a specific duty, namely introducing new members into it. In that capacity she performed a considerable range of work, best exemplifying how fashion facilitated the exchange between gender and class capital.

<24>The first and foremost duty of a fashionable lady patroness was godmothering the “new man” and “new woman.” The latter two referred to those who aspired to enter into Society due to their newly obtained wealth, position, and/or rank. Different from the debutante, they did not have relatives and relations who were already established in the World and could chaperon them: hence their need for godparents. The fashionable lady patroness consequently came into being. In the early half of the nineteenth century, the people she chaperoned included but were not limited to:

some recently-inheriting baronet’s wife; or perhaps, some unexpected peeress, newly smuggled like illicit whiskey, from the bogs of Ireland; or the wife of a President of the Council from Calcutta; or millionary, emancipated by miraculous speculations, from the chrysalis of a city alley. [. . .] Some boy Viscount, fresh from the University, or half-bred man endowed by the caprice of fortune with the hoarded millions of a miserly uncle.(63)

Despite the author’s satirical posture, one can still see that some kinds of the new woman and new man listed here—for example, the nabobs and theirs wives from the colonies and the East End of London—were overlapping with the bourgeois new woman and new man discussed by various scholars such as Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall: both belonged to the emerging middle class. But if the latter embodied a new cultural force that defined itself in antithesis to the old aristocracy, made its debut in society, started to police its boundaries and asserted its hegemony in the 1830s and 1840s—as Davidoff and Hall put it—the former provided a quite different profile to the “emergent class.”(64) The characterizing quality of this profile was merging or integration. Assimilation to the upper-class culture via the route of fashion and fashionable society was the key note here. Although this note has not been taken seriously in British historiography, recent studies of middle-class consumption patterns and life-style in general suggest that the string of assimilation might very well have vibrated together with that of antagonism and was equally important.(65) The debut of the “emergent class” in society at large involved, to a considerable extent, some of its members’ debut in Society in particular. The fashionable lady patroness played a significant role in that debut.

<25>The role was actually dual. On the one hand, the fashionable lady patroness recruited new blood for Society by refining the new woman or new man’s manners, directing her or his expenses, inviting proper guests to her or his parties, etc. As the wife of the American Ambassador wrote from London in 1841:

These things are managed in a curious way here. A nouveau riche gets several ladies of fashion to patronize their entertainment and invite all the guests even if he has a wife. Lady Parke entertained for Hudsons [the railway “king” and his wife] whose guest list included the Duke of Wellington. Lady Parke stood at the entrance of the splendid suite or rooms to receive the guests and introduce them to their host and hostess.(66)

By literally standing at the door of the new man and the new woman, the fashionable patroness like Lady Parke ensured that Society was accessible to the newcomers including such nouveau riches like the Hudsons and that it did not become a site at which “vulgar” wealth ran rampant at the same time.

<26>On the other hand, however, because the major rule the fashionable patroness followed in policing the door of Society was that of the indefinite, circumstanced-based fashion, she could not fully control the effect of her policing. One of its paradoxical functions in the long run was that she lost the role of social doorkeeper. As many people recollected, Society at the end of the century was so expanded that it lost its quality as a distinctive unit whose boundaries could be policed; instead, fashionable society started to take on the meaning that is still alive today, namely the totality of modern consumer society in which business overrides everything else. As Ralph Nevill and Charles Edward Jerningham—two nostalgic late Victorian gentlemen—put it in 1908:

Business before pleasure is its [Society’s] watchword to-day, when the chief concern of the majority is to extend an eager welcome to any wealthy nobody who may seem likely to be of use.

Woman it is rather than man who has brought this state of affairs about—women [. . .] caring at heart nothing about social differences; to many of them, one man is as good as another, and better—if he is rich.(67) Despite their generalization about women’s nature, these authors retrospectively pinpointed the role of the fashionable lady patroness in effecting change in Society by challenging, consciously or unconsciously, established social boundaries. This challenge could have to do with her attempt, not necessarily conscious, to exchange her class advantages for gender disadvantages. If as a woman she was restricted in accessing power, privilege and property compared with a man in the same rank, she also enjoyed the social prestige of high birth, fine breeding, good social network, and simply the aura of being a fine lady. The latter could be used to make up for the former, and fashionable society provided a perfect site for this exchange. As the Court Journal and various other sources documented, the fashionable lady patroness often had at her disposal her protegés’ “houses, carriages, and country seats,” and could borrow money from them which were “never repaid.”( 68) Similar exchange could be found in another important kind of work the fashionable lady patroness conducted: lionizing political, literary and intellectual, musical and theatrical stars.

<27>Lionizing, or making a literary, political, artistic, musical or theatrical figure the fashion of a time was a usual practice in the beau monde, and the fashionable lady patroness played a key role in accepting and placing lions and lionesses in Society. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, for example, Thomas Moore, Samuel Rogers and Henry Luttrell were great lions of Society, and they were patronized by the Tory fashionables like Lady Jersey as well as by the Whig grandees such as Lady Lansdowne and Lady Holland. Later on, Thomas Carlyle became a lion mainly through the introduction of Lady Ashburton; meanwhile Countess Blessington served as the fashionable lady patronesses for young Dickens, Benjamin Disraeli, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, among others. By being Society lions, these bourgeois intellectuals could gain much benefit which their social and economic status would otherwise deprive them of: access to prominent political figures who often moved in the same circles; networking with other literary and intellectual people; enjoyment of conspicuous consumption, which they might not be able to afford as illustrated by Thomas Moore’s frequent use of his patronesses’ opera boxes; some special privilege as in the case of Moore’s son being pensioned by the Whig government largely via his friendship with William John Russell and Lord Lansdowne built up in Society; and indulgence in a sort of pleasant sociability and aesthetic enchantment that wealth, rank and taste combined to produce. The last point can by illustrated by Thomas Carlyle’s attraction to the Ashburton circle. Carlyle’s being drawn by the coterie could certainly have to do with his alleged desire to “get his strenuous ideas of reform into practical currency”— as the editor of Mrs. Carlyle’s letters, Leonard Huxley, put it;( 69) but it was also deeply intertwined with his private enjoyment of the enchanting society a wealthy fine lady with tact, taste and sociability was capable of providing. According to his wife’s letters, Carlyle took “a vast of pleasure” in Harriet Ashburton’s company, visited her house at least “one evening in the week,” went to see her family at their “‘farm” on Sundays” in 1843, and joined their company in Paris in 1851.(70) Nonetheless, this was not a usual man-woman affair—as Samuel Rogers and other acquaintances tried to insinuate by making fun of Jane about her husband’s frequent meetings with the lady—however eroticized the relationship between them might be.( 71) He approached her more as a lively ideal, a symbol of something beyond his usual bourgeois intellectual life, something that had to do with what Simmel would call “the free and princely character of life.”(72) As Carlyle himself wrote to Ruskin, for him she was “a very high lady both extrinsically and intrinsically,” and her parties had the usual elements [of luxury and taste] in their highest perfection that were simply irresistible.(73) This kind of enchantment characterized other intellectual figures’ relationship with their fashionable lady patronesses as well. Lord Lamington, for instance, recorded how Lady Blessington enchanted many men as she “presided over the nightly reunions of all that was most eminent in literature and politics and social distinction.”(74)

<28>Just as a bourgeois intellectual could make up for some of his class disadvantages by associating with a fashionable lady patroness, the latter could also exchange some of her social privileges for her gender disadvantages via the route of fashion. Restraints upon women in the nineteenth century were many, chief among which was the fact that they were not supposed to address public meetings or even publish under their own name. As Peter Mandler frames it, the whole spectrum of the public sphere was perceived as a male arena bolstered up by men’s classic education (which took place increasingly away from home), by the fraternities of the Houses, and by the male arts of public oratory, debate and meeting.(75) Against the backdrop of such gender ideologies and realities, the fashionable lady patroness’s lionizing opened up a space where they could legitimately express their intelligence and realize a certain degree of intellectual development. For instance, as a major means of lionizing, conversazione not only allowed a lady patroness to gather the best minds available within her drawing room and thus keep herself in touch with the latest intellectual development; it could also satisfy her desire to demonstrate wit and manifest intelligence. According to Jane Carlyle, although people who gathered around Lady Ashburton had to “get up fine clothes and fine ‘wits’, sometimes there could be “no strain on one’s wits” because Lady Ashburton did “all the wit herself.”(76) Similarly, a musical soirée or a private theatrical that a lady patroness organized to bring to the World a new star could also be equally important to the lady artistically and psychologically as she lessened her gender disadvantage in the wielding of her social privilege.

<29>In addition to lionizing and god-mothering new members, the fashionable lady patroness had another significant form of work, namely to promote charity via her fashion and fashionability. In this respect, the fashionable lady patroness should be distinguished from the conventional model of patronage. Upper-class women, like the lady of the manor or the lady of the bountiful, had the tradition of presiding over charitable events, at which their role as patroness was largely determined by their ranks and by their families’ alleged prestige in the local communities; and often, the patroness knew the participants—usually her dependents, tenants, neighbors, etc.—who gathered together for a known purpose such as collecting money for the repair of the community church. In this case, patroness-ship was “a thing of inheritance,” and the great lady became “as a matter of course of whatever attempts” to be made “on the indulgence of the provincial public,” as Mrs. Catherine Gore put it.(77) However, by the early nineteenth century, and especially from the second decade on, a new role of fashion emerged: the fashionable lady patroness differed from the old figure in four major ways.

<30>First of all, she used metropolitan London as her major site of charitable activities, and her patroness-ship became “a matter of election.”(78) Only those who were well-known in the beau monde were likely to be chosen, and fashionability was the chief criterion for choice. Then, the procedure of her patronizing also changed. While the final effect might be charity, the event itself was often presented as one of fashion. Long before the event, advertisements about it appeared in magazines and papers, hinting at what fashionables were to patronize the event and soliciting as much participation as possible throughout the metropolis if not all over the country. For example, news about the ball to raise funds for Polish refugees in 1841 occurred in The Times months before hand. In that duration, various other pieces announced the musical star Miss Adelaide Kemble as the lioness and Lady Palmerston and Count D’Orsay among the patronizing fashionables.( 79) Related news also frequently hinted at the limited number of tickets available so that the general public would buy as soon as possible. The mechanism worked not only due to the pervasive power of the press but also because the public wanted to watch, be close to, and get to know the fashionables via a charitable gathering. Indeed, as Nevill and Jerningham recalled, “charity, which includes the organizing of bazaars, to which fashionable people can be induced to come and sell, is not bad” in launching the newly enriched people into Society.(80) Punch pointed to the same practice, albeit with a highly satirical tone, in 1841:

But the fair [by the newly rich Spangle-Lacquers] was expected to be fashionably attended—fashionable families gave it their countenance—the very circumstance of young aristocratic ladies lowering themselves to trade, and playing shop-girls, was fashionable—and very fashionable company were to be admitted the first day at half-a-crown a piece for the mere privilege of entrance.(81)

The frequent repetition of the word “fashionable” vividly conveys the deep intertwinement between charity and fashion.

<31>As fashionable events, fancy fairs, bazaars, and balls were often organized with special attention to novelty and even Arabian-night other-worldly enchantment: a third characteristic of the new model of patronage. As Mrs. Arbuthnot wrote of the 1822 ball for the relief of the Irish in the Opera House:

The House was beautifully done up, the center boxes to the top of the house were turned into a large sort of tent beautifully decorated for the King, & on each side were boxes for the Lady Patronesses & the Foreign ambassadors. [. . .] Everybody was in full dress and it was a most brilliant spectacle.(82)

A “most brilliant spectacle” was exactly what characterized charitable events in the early decades of the nineteenth century; patronized by fashionables, they were becoming increasingly occasions for seeing and being seen. While they might not be less—and indeed could be more—effective in terms of raising the necessary funds, the incomparability between the fashionable motive and the charitable effect challenged the conventional Christian meaning of charity and caused social anxiety, which might account for the existence of considerable amount of satirical literature targeting the fashionable lady patroness—and especially those from the middling ranks—as Punch did. Nonetheless, the role prevailed and expanded the scope of charity; international rather than merely local concern started to catch charitable attention.

<32>As with charity, the fashionable lady also served as a patroness of commerce in three major ways. First of all, belief in the productivity of luxury consumption led to the idea of the fashionable entertainer as an activator of economic circulation indispensable to the welfare of the country. This idea was widely perpetuated in various fashion magazines like the Court Journal. For instance, at the approach of the season in 1832, rumor went that there would be a great cut-down on balls, parties, soirées, etc. Upon this, the Court Journal editor made a call to fashionable ladies:

We cannot but entreat the ladies of the creation to consider the matter wisely […]; we beg them to reflect on the serious injuries which so sudden a fit of sobriety on their parts would produce, among the manufacturing classes, and the innumerable tribes who are clothed and fed by the re-action of those splendid orgies.(83)

The editor was far from alone in this view; the Mandevillian notion that private vices could be public benefits was accepted widely in the early decades, and thus the idle, vane and dissipate lady entertainer was one and the same as the benevolent promoter of social and economic circulation.( 84) Apart from that, the fashionable lady could also be called on to preside over specific events—including bazaars, fairs, fancy balls, etc. — that were understood to be trade-enhancing. For instance, in 1842 when the silver-weaving business was down, related people asked Queen Victoria to give costume parties to promote it. “The Queen yielded to the supplications of the tradesmen to give a fillip to trade, so had the Fancy Ball,” wrote Lady Holland in a letter to her son.(85) Yet another way in which the lady of fashion served as a patroness of commerce was simply to let her name to be used for advertising. It was becoming acceptable for a fashionable lady to allow her name to be attached to a particular event or product. For example, the silver-fork novels popular in between 1825-1845 usually bore “a fashionable lady” in the byline even if they might be written by a bourgeois author. Here, one can see an earlier version of the modern-day commercial technique of using the visibility of a celebrity to sell, not just a particular product, but a special way of life: that of fashion.

<33> It should be pointed out, however, that the emergence of these new roles—just as the rise of the rule of fashion—did not go without severe contemporary criticism in various forms. Chief among which were not only anxious critiques of wasteful consumption of the fashionables, but also the targeting of their sexuality. The woman of fashion was particularly butted as an immoral and sexually loose animal. As the satiric drawing “The English Ladies Dandy Toy” suggests, the fashionable patroness’s lionizing could be atrociously visualized as an aristocratic woman’s playing with and drawing on a dandy’s virility and thus turning him into a skeleton ( Fig. 2).

<34>In spite of such criticisms and dark insinuations, however, the fashionable lady patroness and the chaperone of fashion survived and remained distinctive figures until the 1850s. But when fashionable society turned “smart” and got diluted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the two categories also lost their distinctiveness. Yet what had made them, namely the rule of fashion, obtained and is still with us today even as it turns invisible—invisible not because it has shrunk but because it is everywhere like air. However reluctant we may be to talk about this rule, it shapes our gendered life nonetheless. In this sense, going back to look at the fashionable identities in the nineteenth century might help shift the ground of the still lingering essentialist-and-constructionist debate in current gender studies. For what the profiles of the chaperone of fashion and the fashionable lady patroness reveal is that gender is neither certain essential fixity nor some fluid construction but a continual remaking in the constant crossing of the two. Thus it might not be as important to take sides in the debate as to explore how each age, unable to do away with either, highlight one or the other and negotiate between them—in tune with the rule of fashion.

List of Figures