<1> In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf famously argues that in order for a middle-class woman to write fiction, she needs “money and a room of her own” (4). This vision, of course, does not describe the circumstances of most women in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century London. According to Judith Flanders, author of The Victorian House (2003), a solitary room for writing and reading, whether called a study, a library, or something else, was a rarity for middle-class women.(1) My research on gender and the Reading Room of the British Museum challenges Woolf’s argument, even by her own example. As Adeline Virginia Stephen, she first registered for a reader’s ticket without fees at the British Museum in November 1905.(2) And although Woolf lambastes the British Museum in A Room of One’s Own as a bastion of outmoded sexist male scholarship, this venue in her narrative proves the provocative stimulus for her experimental writing style, the very scene that launches the rest of the hybrid essay.(3)

<2> A public space in the heart of Bloomsbury, the domed Reading Room of the British Museum became the generative site of diverse publications by numerous women, including George Eliot’s research on Romola in 1861.(4) Securing admission to this vast library required no money at all. Unlike a subscription library, such as the exclusive London Library in St. James’s Square, only a letter of sponsorship by a householder (the head of a household, however defined) was necessary to register as a reader at the British Museum from 1857, when the doors to its circular, book-lined reading room first opened. When Woolf applied for a reader’s ticket, her brother Thoby wrote on her behalf as the householder at their 46 Gordon Square address, near the Museum.

<3> In the archives of the papers of the Reading Room of the British Museum are letters of sponsorship by governesses and schoolmistresses, by clerks and shopkeepers.(5) Indeed, as novelist and poet Amy Levy claimed, the Reading Room of the British Museum “attracts to itself in ever-increasing numbers all sorts and conditions of men and women” (Levy, “Readers,” 227). Many of the women who used this space for research, writing, and more importantly, networking, supported themselves through paid research, fact-checking, translating, or writing for periodical publications. Judith Walkowitz has discussed “the bohemian, radical circle of the British Museum” in relation to socialist club life in London, especially Karl Pearson’s Men’s and Women’s Club (140). I want to suggest that this multidimensioinal space facilitated productive encounters, both face-to-face and textual, for Victorian women within Bloomsbury’s big bookroom. As Cass Sunstein has noted, our digital age has increasingly segregated readers and writers through portable screens of their own, very different conditions from the late nineteenth century (23).

<4> In my paper I plan to do the following: first, to offer a sampling from the archives of application letters of women writers who registered in the Round Reading Room during the last three decades of the nineteenth century; second, to explore three readers in particular. Eleanor Marx, Clementina Black, and Amy Levy often met at the Reading Room; their writing engaged with radical issues of the day, and they emphasized in their writing — or practiced in their lives — the importance for women of public, exterior spaces. As “radical” women writers in fin-de-siècle London, Marx, Black, and Levy envisioned social change, particularly reforms that affected the condition of women.

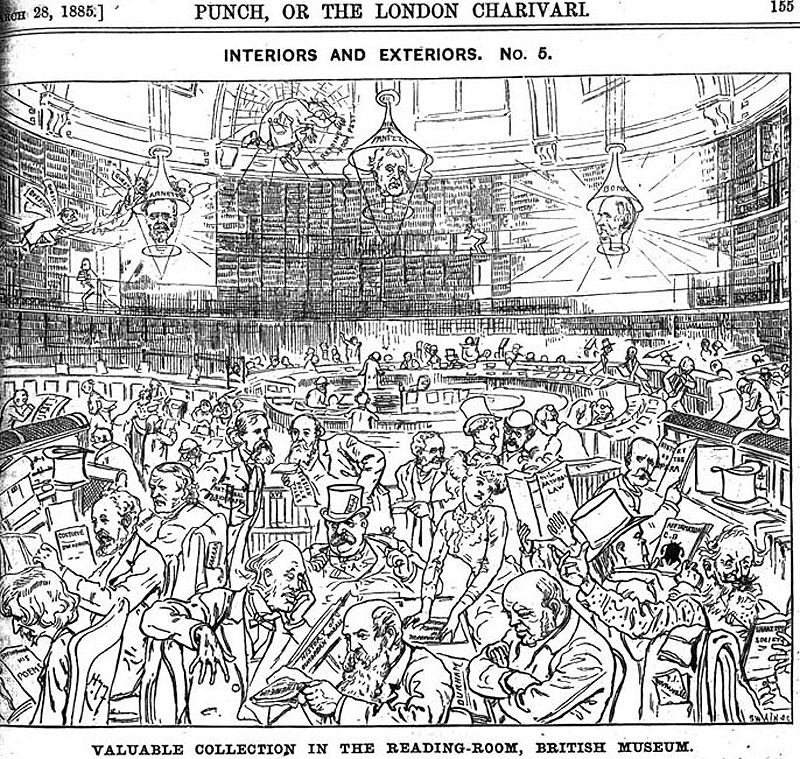

<5> The list of women readers in the signature books for the Reading Room of the British Museum suggests that many aspiring writers in London in the late nineteenth century registered for a reader’s ticket as a matter of course. For example, Annie Besant obtained a reader’s ticket in July 1874, shortly after she separated from her husband and moved to London where she supported herself when Charles Bradlaugh, president of the National Secular Society, hired her to write articles for the freethought newspaper, the National Reformer. Bradlaugh also sponsored his daughter Hypatia’s application for a reader’s ticket in 1881.(6) Under the name Violet Paget, Vernon Lee obtained entrance to the Reading Room in June 1881.(7) She gave “study” as her purpose, a category on the application form, and supplied the Gower Street address of A. Mary F. Robinson, her intimate companion who herself was the subject of a 1885 Punch cartoon titled “Valuable Collection in the Reading-Room, British Museum” [Figure 1].(8) The only notable female figure in this sketch, Robinson appears as a Pre-Raphaelite-styled stunner perched spectacularly on a desk, her hands resting on her 1878 collection of poetry, A Handful of Honeysuckle. Vernon Lee’s application also lists as her sponsor Richard Garnett, the Superintendent of the Reading Room, sketched as one of the suspended and illuminating fixtures in the Punch cartoon. Garnett become a literary mentor for many young women at the British Museum: Robinson, Marx, Black, Levy, and Mathilde Blind.

<6> Two generations of Rossetti women used the Round Reading Room and the resources available in the library there. In her letter of application in June 1896, Olivia Rossetti requested entry to the Reading Room “in order to study the history of the French Revolution.”(9) Her sister Helen registered at the British Museum in December 1900.(10) In 1903 they published under the name Isabel Meredith A Girl Among the Anarchists, a fictional account of their work as adolescent editors for The Torch: A Revolutionary Journal of International Socialism. Both their aunts Christina and Maria had been readers at the British Museum. Christina Rossetti first registered there in 1860 where she pursued scholarly research, especially from 1876 to the early 1890s when she lived nearby.(11) Other notable names of women readers from the Reading Room archives include Mathilde Blind, Beatrice Potter Webb, Ella Hepworth Dixon, and Olive Schreiner, who were members in various radical clubs including the Fabian Society, the Fellowship of the New Life, the Men’s and Women’s Club, and the Socialist League.

<7> By turning to Marx, Black, and Levy, all of whom knew each other, lived in walking distance of the British Museum, and wrote on behalf of disempowered groups of women, I want to explore the significance of different kinds of rooms that figure in their publications. They decry the domestic sphere as a space of debilitating isolation for both poor and middle-class women. As I’ll show, the factory figures either metaphorically or literally as a public space of beneficial social and economic conditions. In Levy’s writing on the British Museum, anticipating Woolf’s by four decades, the Reading Room as a “workshop” of writers and readers is also a “refuge” for “all sorts and conditions of men and women.” Both Marx and Black supported reforms for women workers in factories rather than private lodgings, a position often at odds with other middle-class feminists who advocated for poor working women to remain at home.

Eleanor Marx

<8> In October 1877, Eleanor Marx addressed the following letter to the principal librarian of the British Museum: “Sir, I am desirous of obtaining a card of admission to the Reading Room of the British Museum, & should be much obliged if you would kindly send me one. I do not know whether it is necessary to mention references. If so I suppose it will suffice to say that my father, Dr. Karl Marx, visited the Reading Room daily for nearly 30 years.”(12) Marx’s father had enlisted his older daughters Laura and Jenny in “devilling” — unpaid literary labor — for him at the British Museum during the 1860s when Eleanor Marx was a child. She herself first came to the Reading Room as a hack researcher/writer for Frederick Furnivall (pictured bottom right in the Punch cartoon) who hired Marx to research and write copy for Furnivall’s Philological, Chaucer, or Shakespeare Society pamphlets. That Marx took on hack writing for income is evident in a letter to her sister Jenny in 1882: “After all work is the chief thing. To me at least it is a necessity. That is why I love even my dull Museum drudgery.”(13)

<9> According to an unsigned letter, Marx’s reading interests ranged far beyond Shakespeare while a hack writer for Furnivall: “I saw Eleanor in the Museum yesterday. She fairly danced with anger. I told her that the translation of the Kama Sutra was locked up in the Library, and refused to women. See if she don’t get it!”(14) Often attributed to Olive Schreiner, these words about Marx were more likely written by another radical woman writer, Margaret Harkness, also a friend of Marx and a regular reader at the British Museum whose journalism and fiction chronicled the deplorable conditions of the East End poor.

<10> Beatrice Potter Webb mentions in her diary meeting Marx in the British Museum refreshment room in 1883 with this note: “Gains her livelihood by teaching ‘literature’ etc., and corresponding for socialist newspapers....Lives alone, is much connected with Bradlaugh set, evidently peculiar views on love....Should think the chances were against her remaining long within the pale of ‘respectable’ society” (MacKenzie and MacKenzie, 34). These “peculiar views” likely allude to Marx living openly from 1884 with Edward Aveling, also a socialist activist. Marx, or Marx Aveling, as she called herself once she began living with Aveling, was active in the early years of the Social Democratic Federation, then resigned along with Aveling and William Morris to launch the Socialist League.

<11> In the same year 1886 as the note about Marx attempting to read the Kama Sutra at the British Museum, she and Aveling wrote a pamphlet on “The Woman Question” and she completed the first English translation of Madame Bovary, still in print today. Marx also translated her British Museum friend Amy Levy’s novel Reuben Sachs into German. From 1887, Marx became involved in labor reform, including the plight of East End Jewish “sweated” workers. After participating in the “Bloody Sunday” 1887 labor demonstrations, Marx published an article about police mistreatment of women activists: “In the fight for free speech now being waged in London a great number of women are doing their fare share of the work, and are fully prepared to bear their fair share of the blows and the ill-usage,” she wrote, but then observed how the police “singled out” women.(15) Yet despite her direct observation of the gendered hazards of an activist public life, Marx urged such engagements in the public sphere rather than the isolation of genteel feminine domesticity.

<12> Marx’s preference for shared public space in contrast to the hazards of private space, an even duller and more dangerous drudgery, surfaces in her little-known play, “‘A Doll’s House’ Repaired,” co-authored with Israel Zangwill. Marx and Zangwill satirize not Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House,” but the English public reaction to it, often punned as “Ibscenity.” The infamous final stage direction of Nora Helmer slamming the door on bourgeois domesticity was an in-your-face gesture of a woman entering the public sphere instead of remaining at home. This open-ended closure invited sequels immediately after the initial London performance of “A Doll’s House” in June 1889, attended by Marx, Black, and Levy. Walter Besant’s version, “The Doll’s House—And After,” fast forwards twenty years later to show the disastrous consequences of Nora’s exit from family life. The deserted husband Torvald is a chronic drunkard, the two sons have fallen into drink and gambling, and the daughter pathetically perseveres to support herself and her father through needlework. Besant writes, “She was in the ruined home cursed by the sins of her parents!” (Besant 323). Nora, however, is a thriving forty-seven year old woman who writes New Woman novels: “In them she advocated the great principle of abolishing the family, and making love the sole rule of conduct” (Besant 320). She offers to teach her miserable daughter to become “free in thought and free in life” (Besant 322), but Emmy Helmer refuses; after she is jilted by her lover because of her ignominious mother, she commits suicide. George Bernard Shaw’s sequel attacked Besant’s reactionary vision by blaming the daughter’s suicide not on Nora but on the hypocrisy of middle-class respectability replete with many “cupboard skeletons” (Shaw 201). Shaw’s Nora observes that “the man must walk out of the doll’s house as well as the woman” (Shaw 206), a repudiation of the traditional familial private sphere.

<13> Marx and Zangwill’s parody “repairs” the last act. In this version, the play concludes not with Nora slamming the house door as she leaves, but instead Torvald’s “bedroom door bangs” as he relegates Nora to the study until she learns her “holiest duties,” as the script puts it, “to keep up appearances” and obedience to her husband (Marx Aveling and Zangwill 250).(16) Clearly a parody of the new public woman of fin-de-siècle London, Marx and Zangwill give these lines to Torvald on the subject: “It is a degradation, a destroying of all that is sweetest and most womanly. It makes them flat-chested and flat-footed. The women of our class should be guardians of the hearth; the spirit of beauty and holiness sanctifying home-life. And then it is ugly to see a woman work. It shocks one’s sense of ideal womanliness. And what is worse, it makes the wife independent of her husband” (Marx Aveling and Zangwill 244-45). By this send up of Nora’s work outside the home, this “repaired” script emphasizes the class and gender analysis embedded in both Ibsen’s play and its English sequels.

Clementina Black

<14> Also in 1877, the year Marx applied for a reader’s ticket, Clementina Black wrote to secure admission to the Reading Room.(17) Identifying as a novelist in her letter of application, Black indicates her Regent’s Park London lodgings where she lived with her sisters. Black had just published her first novel, A Sussex Idyl, about a cross-class romance between a London law student and a young woman from a farming family in which Black updates the pastoral tradition by concluding with the married couple relocated to London. Like Harkness, Black supported herself largely through her publications including several novels and many magazine articles on the plight of poor working women. Also like Harkness, her journalizing about unions and women workers slipped into her fiction, especially her 1894 novel An Agitator, the story of a union organizer. A sketch of Black in a woman’s magazine in 1892 named Black as one of two “chief motors in the work of promoting union among women-workers.”(18) Black was a leader in the Women’s Protective and Provident League, later renamed the Women’s Trade Union League, and her activism in the form of published essays, speeches, and fiction, concentrated on the sweated home labor of East End women.

<15> In articles appearing in a range of magazines from Oscar Wilde’s Woman’s World to The Nineteenth Century and The English Illustrated Magazine, Black argued that factories were a superior venue for working women over domestic lodgings in part because such arenas were more conducive to union organizing. Also like Harkness, Black aided Annie Besant in the labor clash between matchbox workers and employers that led to the 1888 strike of Bryant and May, which resulted in better conditions for many female factory workers. In her 1892 essay, “Match-Box Making at Home,” Black details several reasons why home workers are disadvantaged compared to factory workers, including irregular and excessive hours and lower pay, conditions which “the power of combination” of women workers in a common space can rectify, precisely the result of the match girls strike at Bryant and May. The following year, Black wrote in an article “The Dislike to Domestic Service” that “there are too many households in which an unprotected girl is liable to temptations and insults from which she would be safe in most factories and workshops” (Black 455). She concludes by urging mothers of working-class young women to guide their daughters toward “factory work” rather than domestic service.

Amy Levy

<16> Amy Levy noted in her diary for 1889 frequent visits to her close friend “Clemmy” Black at “the office” of the Women’s Trade Union League, located around the corner from Levy’s Bloomsbury home and walking distance to the British Museum. Levy’s name appears on the donation lists of this league, and she stipulated that profits from her posthumous publications following her suicide in September 1889 should go towards Black’s “philanthropic work.”(19) Although Levy never aligned herself with a specific political position, as Marx did, nor was an activist on behalf of poor women workers, like Black, her close friendships with both of these women offer contexts for Levy’s discussion of the Reading Room of the British Museum as a “workshop” of textual laborers. Levy applied for a reader’s ticket in November 1882 when she turned twenty-one, the age requirement for entry.(20) She had spent two years studying classical and modern languages and literature at Cambridge University where she was the first Jewish student at Newnham College (Bernstein, 15-16). Levy’s notebook which she titled “British Museum Notes” makes evident how she used the Reading Room not only as a networking station, but also for research and writing. The notebook includes a draft of an essay on Christina Rossetti, published in The Woman’s World in 1888, as well as a good chunk of what became the short story “Eldorado at Islington,” also published in Wilde’s magazine (Bernstein, 22-24). In this story Levy unfolds the cramped life of Eleanor Lloyd who lives with her family in genteel poverty in London; from her “window in the roof” Eleanor catches tempting glimpses of public life. The narrator comments, “Eleanor, who was a ‘lady,’ (Heaven help her!) used sometimes to envy the barmaid and the flower-girls their social opportunity.”(21)

<17> In contrast to the claustrophobia of threadbare home life in “Eldorado at Islington,” the Reading Room of the British Museum functions as a space in Levy’s writing where various opportunities abound. On the opening page of her 1889 essay, “Readers at the British Museum,” Levy claims, “The ‘Room’ has indeed become a centre, a general workshop, where in these days of much reading, much writing, and competitive examinations, the great business of book-making, article-making, cramming, may be said to have its headquarters” (Levy, “Readers,” 222). Levy also fashions the Reading Room as an egalitarian space with “wonderful accessibility” for a wide spectrum of visitors traversing boundaries of class, gender, and occupation: “For some it is a workshop, for others a lounge; there are those who put it to the highest uses, while in many cases it serves as a shelter,—a refuge, in more senses than one, for the destitute” (Levy, “Readers,” 227). Published in Atalanta, a magazine aimed at young women, the article envisions the Reading Room of the British Museum as a multipurpose space, a knowledge factory, a club, a workhouse, thus melding together public and private, working and middle classes, scholarship and commercial production with social exchange. The drawings that accompanied this essay [Figure 2] suggest women as sturdier and more studious than men readers at the museum in contrast to many accounts in the press complaining about the influx of “lady readers” as Reading Room irritants.

<18> Both Levy’s 1889 Atalanta essay and her 1888 short story set in the British Museum implicitly challenge published complaints about women in the Round Reading Room. That Bloomsbury’s big bookroom attracted an unprecedented number of women into its domed sphere is apparent in a spate of articles in periodicals of the 1880s. In 1886 The Saturday Review ran a short piece titled “Ladies in Libraries” whines about a horde of women enjoying the British Museum by doing anything but serious reading: “woman makes the Reading Room a place where study is impossible....woman talks and whispers and giggles beneath the stately dome...she flirts, and eats strawberries behind folios, in the society of some happy student of the opposite sex. When she does read, she is accused of reading novels and newspapers, which she might better procure somewhere else.”(22) Levy’s article and story provide counter-examples to the image of silly lady readers populating the periodical press. The accompanying sketches of a spectacled “fair reader” and another female figure “reaching after knowledge” in contrast to one male reader “tottering under the weight of knowledge” and the male figure reading “lighter literature” provide a visual analogue to Levy’s argument.

<19> For Levy, the British Museum provided a site in which different kinds of knowledges collide in provocative ways. Her short story, “The Recent Telepathic Occurrence at the British Museum,” appearing in the inaugural issue of Oscar Wilde’s magazine, The Woman’s World, correlates mundane and radical notions of knowledge. By staging a “telepathic” encounter between a seedy and dim-sighted professor and a young woman, presumably once his university student, Levy draws on contemporary debates on scientific spiritualism. Frederick Myers coined the term “telepathy” in a speech to the new Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in late 1882. From her Newnham contacts, Levy knew Myers and several others active in the SPR, and recounted a conversation between Myers and others: “Talked of the immortality of the soul. Thinks it will be proved scientifically!” In Levy’s tale about unrequited love, the professor — after grumbling to himself about women readers as noisy nuisances at the British Museum (although the narrator makes clear that the source of his distraction are chatty men) — sees “at the outer circle of the catalogue desks” the unnamed woman staring at him in an “unearthly fashion” (Levy, “Telepathic,” 432). Not only does the story ridicule the professor’s misogynist rage over what the narrator calls “the oft-vituperated rustle of feminine skirts” in the Reading Room, the narrative also contrasts the professor’s impaired eyesight with insight and wisdom, encapsulated by the visionary appearance of the woman near the card catalogue. By employing the telepathic phenomenon known as “the crisis-apparition-at-death,” Levy correlates knowledge of the mind and eye with knowledge of the soul and heart. In doing so, this “telepathic occurrence” redefines the Reading Room as a multi-dimensional space for apprehending different kinds of truths.

<20> My brief exploration of this celebrated venue extends the “material turn” in recent literary studies — such as Leah Price traces in her introduction in the January 2006 PMLA — into this national library, for the spatial and social conditions of reading and writing complement the role of physical books and their contents. As Marx, Black, and Levy suggest in different ways, the Reading Room of the British Museum figured as a site of commercial opportunity, spiritual illumination, and activist and professional networking for women writers who rewrote the space of knowledge itself.

Figures