<1>In 1875 the British master mariner Henry Harvey had been sailing for over 20 years, embarking on international voyages that took him away from his wife and three children for over a year at a time. In the memoir he wrote for his children he described their sleeping habits, prior to his most recent departure. “Daisy”, Harvey recalls, “was in the habit of going to bed with four dolls which she used to arrange very comfortably so that the large one with the great wooden head used to tumble out about midnight with a startling crash…Lillias had her amusement in sleeping in a sailor hammock I had made for her” ([n.d], 22). Harvey had made the hammock as a gift for his child. The handmade object fulfilled some of the parental function Harvey was unable to perform whilst at sea; it cradled Lillias as she slept, it entertained and amused her. The hammock acted as a nurturing material link between Harvey and his daughter and a proxy paternal presence in his absence. Significantly, Harvey used his sailor’s skill and acumen to make this object. Hammocks were made from duck canvas panels, edged with knotted rope. The techniques involved in the construction of a hammock, like all objects worked from rope, would have been taught to Harvey by another sailor, in the early stages of his seafaring career (Goodall 1860, 64).

<2>A children’s cot made by sailor Robert Milliken, similar to the hammock crafted by Harvey, is held in the collections of the National Maritime Museum (Figure 1). Rectangular in shape, the cot is constructed out of thick canvas, with high sides to keep an infant from rolling out (Figure 1). The duck canvas has been hand-sewn, using the same needle, palm(1) and stitch with which sails were made and mended. The suspension cords are worked in crown sennit, a technique used for its durability as well as its decorative potential (Smith 1990, 127), and half-knotted decorative fringing hangs around the edge of the cot. Milliken made the cot whilst working on the Prince Line, carrying emigrants and cargo between Europe, Brazil, South Africa, India and the Far East. Milliken was born in Magee Island, Ireland, in 1878; he left Antrim at the age of 16, as a Boy on a Nova Scotian sailing ship, before working his way up to the rank of master on a steam ship a decade later (‘Robert Milliken’ 1894, 1900, 1902 & 1904). Milliken clearly invested a substantial amount of time and labor in the object’s construction. It is unclear, however, whether he made this functional and decorative item for his own child, like Harvey, or for a young passenger in his care.

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

<3>As examples of sailor-making, Harvey’s hammock and Milliken’s cot suggest that deep sea sailors in the long nineteenth century existed between two emotional communities: One at sea, composed of sailors and passengers, and one at home, populated by a sailor’s family. The construction and use of Harvey and Milliken’s hammocks further suggests that these men used craft to negotiate between the two groups. Sailors utilized their hand-making skills, learnt from other seamen as they were inculcated into the trade, to facilitate continued emotional contact and presence within a familial community. This article will explore the role that hand-making and hand-crafted objects played in a sailor’s significant relationships. I will ask, as other scholars of emotion have asked, “how do people make objects in the expectation of being moved and of moving others?” (Downes et al. 2018, 11). First, I will position hand-making as an emotionally transformative act for its practitioner, through which objects are invested with social and emotional agency. The second section will consider craft in a ship-board context; exploring communal craft’s ability to strengthen and reify interpersonal bonds. As Janice Helland et al. have suggested, craft is a material process that marries an individual with a community and context; craft practice “speaks of a relationship between place and producer” (2014, 3). The final section will examine craft within the context of a sailor’s relationship with home and its inhabitants. I will suggest that shared craft practice and gifts created material and ideational connections between sailors and their significant others. This follows scholars such as Michael Roper (2010) and Holly Furneaux (2016) who study relationships conducted at a distance during wartime.

<4>The emotional experiences and practices of sailors have been largely unexplored. Studies concerning sailors within the fields of emotional and cultural history have tended to focus on their representation within popular, visual and material culture, exploring their impact on the cultural life of Georgian and Victorian Britain (Conley 2009; Land 2009; Begiato 2015). While this work is important in understanding the nation’s emotional response to the sailor, there is a paucity of research into sailors’ own emotional response to vocation, gender and familial connection. A notable exception, written by the ethnographer Knut Weibust, endeavors to uncover the ‘adaptive processes’ enacted by sailors in response to the emotional stress and strain of going to sea (1976, xii). Weibust identifies dangerous working conditions, vulnerability to weather and wreck, and the difficulty of leaving one’s family as the principle causes of anxiety in nineteenth-century seafaring communities (100 & 418). The present study centers on the subjective and emotional experiences of the sailor, and his responses to the effects of his vocation on his social environment and family life. I highlight how sailors employed craft as an adaptive emotional process, as a reaction to a life lived on sea and land. I will add to the growing body of scholarship, lead by the Port Towns and Urban Cultures project, which concerns itself with the cultural and social lives of sailors and their navigation of the experiential and geographical space between sea and land (Beaven et al 2016).

<5>The shipboard and landed social groups in which nineteenth-century sailors circulated can both be termed “emotional communities”. As theorized by Barbara Rosenwein, an emotional community is a social group with agreed parameters of emotional response and expression, or a “system of feeling” (2002, 842). An emotional community collectively recognizes “the emotions that they value, devalue, or ignore; the nature of the affective bonds between people that they recognize; and the modes of emotional expression that they expect, encourage, tolerate, and deplore” (842). Constituents of a particular emotional community follow the communal system of feeling in how they respond to stimulus, engage in emotional relationships and express emotions. Rosenwein recognizes that people may belong to multiple social groups with varying emotional expectations and systems of feeling. People move between emotional communities “adjusting their emotional displays…to these different environments” (842). In the case of sailors, this involved moving between two emotional communities, one at sea and one at home. This article will demonstrate that sailors used different emotional parlance and forms of expression when fostering emotional relationships on board ship, compared to those he used within his familial home and landed community. Furthermore, I will show that craft practice provided an apposite medium through which sailors negotiated relationships within both emotional communities.

<6>In order to investigate the emotional potential of sailors’ craft practice, I bring together two strands of historical testimony – the extant sailor-made objects in the collections of maritime museums and the textual traces of making practices recorded in the published memoirs of nineteenth-century sailors. The memoirs and makers I have chosen, where known, are working class. Some, like Henry Harvey, who grew up in Limehouse (‘Henry Harvey’, 1841) and became an apprentice seaman in 1845, strove to make a career at sea and progressed up through the ranks of the merchant navy (‘Henry Ralph Harvey’ 1845, 1853, 1854 and 1856). Others, like Robert Hay and Alfred Spencer, were born to large poor families and joined the Royal Navy as young men seeking adventure (Hay 1953, 28; Spencer 1983, 2-3). Christopher Thompson came to the sea not as a sailor, but having learnt a trade. He was apprenticed to a ship builder in Hull, through a charitable scheme for indenturing poor boys, which he left prematurely to sail as a carpenter’s mate (Thompson 1847, 58). The course of the professional and family lives of Harvey, Hay, Spencer and others can be traced via their service certificates and census records, whilst insight into their environment is taken from other published accounts.

<7>The makers described here lived and worked on both steam and sailing ships, undertaking voyages of whaling, trade and war. Different industries, during a period of technological and sociological change, created varying working conditions. However, these men all existed within thrown-together, yet isolated communities in which they lived in close-quarters for long periods of time at sea. During these voyages, it was necessary for sailors to be regularly absent from the home and at a considerable distance from significant others. One of the ways in which sailors responded to these conditions was craft. Sailors were crafters who used their material creativity and skill to negotiate the conditions of their vocation. Working patterns and conditions, such as the allocation of shore leave, the ratio of work to idle time, the meting out of discipline and the size of crew, varied considerably between the Royal and merchant navies and the whaling fleet. The Royal Navy itself underwent significant change during the nineteenth century; from the violently restrictive Georgian navy of impressment, regularly engaged in sea-battle, to the more pastorally engaged Victorian navy of the Pax Britannica, in which seamen built careers and earned a pension. The broad view taken in this article, in terms of periodization and also ship-based industry, allows a glimpse of the continuities in sailors’ responses through craft to the common conditions of sea-faring.

Sailors and Craft

<8>The nineteenth-century sailor was a proficient and prolific maker. Men at sea would carve, knot, embroider, sew, paint, and tattoo. Sailors repurposed the tools and techniques they used in their everyday sea-faring labor for creative purposes. Jack-knives became implements for carving and inscription (West 1995, 51), while the sail-making needle was used by tattooists (Lodder 2015, 206). Men used their skills to decorate their personal belongings, as well as making objects from scratch. Working tools and handkerchiefs were initialed or embellished with a small floral design, while larger projects could include decorating a ditty box or embroidering a ship’s portrait. Sailors used the materials to hand; they crafted with wood, bone, unpicked rope and other scraps found on board (Pawson 2016, 11). Sailors were improvisatory makers, who responded to their material environment.

<9>Tim Ingold explores in detail “what it means to make things” and particularly how the craftsman “thinks through making” (2013, 6 & 21). Ingold describes how the craftsman and crafted object engage in a dialectical and sensorial relationship, in which the maker experiments with the material through physical intervention. Each intervention is successful or unsuccessful, as influenced by the properties of the material itself, the abilities of the craftsman or the quality of his tools, and the maker will alter his practice accordingly. This process of trial and error, intervention and correction, can be seen in sailors’ work. The hand of the maker is seen in the varying depth of an incised line, or the changing tension of stitches, where the craftsman has applied more pressure to create a more definitive line or drawn the thread less tightly to keep the ground from puckering. These modifications indicate a sailor-maker’s close engagement with the material at hand. Ingold describes this as the “improvisatory creativity of labor that works things out as it goes” (20). Rather than the craftsman being an autonomous creator, the end product is equally influenced by the material from which it emerges. This is a collaboration between maker and object. Creative thought is not generated internally but is brought about by the dialectical and sensorial relationship between maker and made-object. “The way of the craftsman,” according to Ingold, “is to allow knowledge to grow from the crucible of our practical and observational engagements with the beings and things around us” (6).

<10>Like Ingold, Alfred Gell refers to the dialectical relationship between maker and made-object during processes of production. Gell describes the connections between beings and things, makers and objects, in relation to agency. Gell explores the way in which objects develop agency and are enabled to act upon and elicit responses from people and communities (1998, 16). The social agency, or causal ability, of the object is derived from the maker or from what the object represents. The object is empowered to act upon people and communities during its life as an object-in-use, as if it were the maker or subject. In processes of production, as the maker acts upon the object, physically, mentally and emotionally, he empowers the object as an agent. The object, in close contact with the maker as it continues to be worked, acts upon the maker and elicits an affective response (45). Here, the dialectical and sensorial relationship of hand-making engenders change in the craftsman, and this change can be conceptualized as an emotionally transformative experience. Craft is a not simply thinking through making, but feeling through making too. Common feelings in material production might include frustration at perceived failings or pride at craft achievements. Less material, bounded and recognizable feelings also come about during creative practice. And, as will be suggested here, emotions engendered by craft production can be indefinable, varied, changeable and not limited to one person. Emotional responses will be shown to be specific to the context in which objects are made, and the way they are used.

<11>The nineteenth-century sailor who engaged in craft recognized the experiential and emotive aspect of making and craft’s transformative potential. In his memoir, Henry Harvey described his craft practice during a voyage in which he was “very ill”.

I wanted a square box for my sextant and thought I would try and make it and succeeded so well that I made another and a work box and then more work boxes which I inlaid with ebony and then at St. Helena I bought some French polish and polished the thing up and they looked so well that I kept on working and found my health daily improving ([n.d], 93).

Harvey’s account demonstrates the dialectical relationship of craft, as described by Gell and Ingold. Harvey’s foray into craft, in making a box for his navigational equipment, was experimental. He was unsure of his abilities, though decided to ‘try’. As he made his first box, he would have had to improvise as he labored; he would have used unfamiliar tools and adjusted his technique as the material responded to his handiwork. Through the practice of making, Harvey enters into a relationship with the object he is constructing, which enables the craft process to have a transformative effect on him. His success in craft engendered a positive feeling, leading him to eagerly and rapidly begin a new project. He continued to challenge himself by making different types of box, honing his skills and trying out new techniques and finishes such as inlay and polish. Harvey relished his new relationship with craft and later in the passage, he proselytized “there is no cure for mental or bodily sickness like hand labor" (93). This compelling testimony recognizes the emotionally transformative effect on a solipsistic craftsman, but it also invites investigation into whether the affective power of making can be carried over into interpersonal relationships.

Emotional Communities on Board Ship

<12>The emotional community on board ship existed within a hierarchical and close-quartered environment, which could sometimes be violent. The sailor William Robinson, who joined the Royal Navy in 1805, highlights the constricted nature of being at sea, suggesting that individual agency is curtailed. He writes, “whenever a youth resorts to receiving ship for shelter and hospitality, he, from that moment, must take leave of the liberty to speak, or to act” (1973, 25, author’s emphasis). Conditions outside of the Royal Navy were not as authoritarian, although sailors could still be subject to bullying (Behenna 1981,10) and conditions were still cramped (Carter 2014, 37). Space and time were regulated and the working and non-working day was rigorously scheduled. A twenty-four hour period was divided in to four- and two-hour shifts (Spencer 1983, 32) and these portions of time denoted when a given group of men worked, slept, ate, or unwound, and when they were allowed to be in the space in which these activities took place. Within this closely-populated and restrictive environment, however, strong emotional connections were forged. James Hannay, who served in the Royal Navy for five years in the 1840s, writes about the “intimate” friendship between Berkeley and Percival in his semi-autobiographical account of sailor life. Their closeness was such that Berkeley’s laugh “raised an echo in the innermost recesses of [Percival’s] heart” (Hannay 1848, 13). Intimate friendships were afforded special privilege. Robert Hay recounts his role in the funeral of his close friend, Jack Gillies, whose coffin was “carried on the shoulders of eight of his messmates.” Hay recalled,

After profiting by Jack’s instructions, enjoying his unbounded confidence and unshaken friendship for six years, I had the melancholy consolation of closing his eyes, of attending his funeral as chief mourner, of dropping a tear and waving the Union Jack over his untimely grave (1953, 74-75).

Sharing and Teaching Crafts

<13>Instruction and craft skills were central to Hay and Gillies’ friendship. In his memoir, Hay wrote passionately on his friendship with the older sailor, under whose care he was placed when he first joined the Navy in 1803. Gillies taught him good seamanship, including sail-making, repairing clothes and making shoes, as well as rigging and steering the ship (70). The two men spent a significant amount of time together, undertaking the shared task of preparing dinner for the rest of their mess-mates (73). The two also demonstrated their connection through exchange. On one occasion, Gillies bought Hay a second-hand book (even though Gillies was illiterate and would therefore be unable to read it himself) and every day Hay saved his own allowance of rum to give to his friend (73). In his memoir, Hay reverently described his friend’s skilled and varied craft abilities,

Jack excelled in all […] He had in his youth been taken by a privateer and was two years in a French prison. There he had learned a great many ingenious things; and from the making of a minor three-decker, with all her sails and rigging complete, to the pricking of a mermaid on the arm of his messmate, or carving a dolphin on the handle of his knife, nothing came amiss to him […] All these acquisitions and more were at my service (71-72).

<14>This account offers a tantalizing insight into the range of craft practices performed on board an early nineteenth-century naval ship. Hay highlights tattooing, carving and ship-model making as evidence of Gillies’ “ingenious” creative abilities. Significantly, Hay was able to learn from Gillies thanks to their close friendship. The instruction of craft skill was foundational to the system of mentorship, collaboration and skill-exchange through which their relationship began and was maintained.

<15>While Hay does not describe the learning process in detail, we can conceive of the time that he and Gillies spent crafting using Ingold and Gell’s descriptions of making. Ingold positions the ‘crucible’ from which a craft object emerges between the experimental intervention of the craftsman and the material response of the crafted object. This dialectical and sensorial relationship is the process through which making and skill development take on an experiential role. In a teaching scenario, one craftsman teaching another, the dialectical and sensorial relationship is expanded to include another maker, whose instruction and material intervention also has a significant bearing on the outcome. Therefore, the experiential and emotional aspect of the craft process can be seen to work on all participants. Gell suggests that the transfer of agency is contiguous - it is transferred from the maker to the object and then back again. In exploring the process of crafting as practiced by friends, it can be suggested that the emotional experience of the relationship and of working together, invests the object with social agency. Once invested with the emotional agency of an interpersonal bond, the object and process reflexively act upon their makers. Therefore, for Hay and Gillies, their existing emotional connection was amplified and reified by working together in the process of craft. I suggest that this heightened state of closeness seeped into the objects, materials and practices with which they worked, which then took on emotional significance. Craft and learning provided a space through which Hay and Gillies practiced and communicated their emotional connection to one another.

<16>Alfred Spencer also referred to the emotional aspect of the transmission of craft skills within a pedagogical relationship, in his description of Jimmy Pye, the bosun’s mate. Spencer idealized Pye as “the very man to captivate a boy’s imagination” and a “real son of Neptune” (1983, 18), devoting a lengthy description to his sailor credentials. For Spencer, Pye embodied the sense of heroism, adventure and glory associated with sailors in the nineteenth century:

in his presence one breathed the very atmosphere of the ocean, and dreamt of naval battles and the search for hidden treasure. He was a man to inspire men and to lead a forlorn hope...his strong arms seemed all muscle and the veins on them stood up like whipcords. He was clean shaven, had sharp features and clear blue eyes and was as nimble as a cat. His face was tanned by the weather to a dark reddish brown, and so too was his breast where it was exposed…showing the upper part of some figure [that] was tattooed on his breast… Usually Jimmy Pye taught the making of knots and splices and it was a pleasure to learn from him (18-19).

With his sun-darkened skin and tattooed breast, Jimmy Pye bore the marks of a long sea-faring career. Spencer pays particularly close attention to Pye’s body, which had taken on physically metonymic characteristics of a life at sea - his veins stood like the ropes he worked and he had clear blue oceanic eyes. Spencer came into contact with Pye in 1865, as he joined the training ship HMS Vincent, moored near Portsmouth (14). He was one of the team of instructors who trained boys in naval skills, such as gunnery, and educated them in reading, writing and arithmetic. Working with the rigging of a ship necessitated the use of many different types of knots, which required a sophisticated eye in order to identify the sort of knot needed and the skill to tie it (Rediker 1987, 92). The knots used for rigging were also adapted by sailors for domestic craft such as sea-chest handles, floor mats and bell-pulls (Smith 1990).

<17>The relationship between Pye and Spencer is indicative of a more formal approach to training naval entrants than described by Hay 60 years earlier. Whereas Hay was expected to learn the ropes whilst on the job (in conjunction with an experienced mess-mate), Pye lead a group of several boys through timetabled classes, on a designated training ship. Craft instruction retained its emotional potency, however, as Spencer took great pleasure in observing Pye work, with a view to replicating his actions. He writes, “I was always delighted to be under his tuition and watched his every mood and movement.” Spencer continues, “it was a pleasure to learn from him. To see his strong supple fingers join two ropes together was a sight in itself, and very poor imitations we made when we followed him” (1983, 19). The borderline-awe which Spencer felt in conjunction with Pye, in watching and learning from his physical interventions with rope were followed by the anxiety of being unable to match his skill. The process of ‘show and do’, in which an instructor demonstrates a practice and an instructee copies, adds another dimension to the reciprocal and reflexive element of craft production. Here, haptic connection, physical intervention, material response and the appraisal of work are practiced among multiple parties simultaneously.

<18>Thorsten Gieser recognizes the emotional connectivity between instructor and instructee during craft practice and the centrality of this connection to learning. Through observation, the instructee is drawn into the dialectical and sensorial relationship between the instructor and the material being worked. Gieser suggests, “to follow someone’s movements is therefore to become involved in a relationship or, in other words, to feel into this relationship” (2008, 312 author’s emphasis). This leads to an emotional and empathic connection forming between the two participants, through the physically metonymic movement of copied craft practice. Gieser describes this as the “creation of rhythm through the reciprocity of movement between apprentice and teacher” (314). The emotional aspect of craft is described by Gieser as fundamental to the development of craft skill, in which “emotions trigger attention” and the ability to learn (305). This would suggest that the emotional connections that sailors developed with their instructors were central to their development of craft skill, as well as having importance in the creation of stronger interpersonal bonds.

<19>Hay’s testimony above demonstrates craft as a practice through which he and Gillies affirmed and played out their emotional connection over time. Spencer, however, highlights the emotional experience of craft as it was practiced. Spencer draws a strong connection between the adventure and glory of sea-faring, Pye’s knotting skills and his embodiment of this idealized sailor character. This connection clearly had a significant emotional impact on him during knotting lessons, in which he followed Pye’s movements, and also in retrospect. It is unclear whether the emotional draw of Pye enabled Spencer to develop his knotting abilities more quickly, but they certainly created an urgency for him to learn and anxiety around the inadequacy of his imitations. For young entrants, craft was an introductory practice, through which sailors’ stripes were earned and relationships forged in emotionally charged sessions with older sailors. Craft was a practice through which they could express their excitement about the navy, but also one in which anxieties about inadequacy could play out.

Emotional Communities at Home

<20>Unlike the physically close relationship with his mess-mates, a nineteenth-century sailor’s familial, courting or marital relationships were defined and demarcated by prolonged absences. Whereas the emotional community of the ship was characterized by proximity, the emotional community of the home was defined by separation. During Robert Hay’s service in the Royal Navy, he did not see his mother, father or ten siblings for 8 years and 3 months (1953, 25 & 239). Whaling men from the Shetland Isles would spend six months a year at sea, while their families gained income through agricultural labor. They were picked up every spring by ships en route to the Arctic. (Trotter 1979, 20). Voyages to the Pacific whale fisheries lasted much longer. In the 1820s, William Dalton (a ship’s surgeon rather than a sailor) embarked on two South Seas whaling voyages, lasting two years and ten months and two years and eight months (1990, 32-33). Henry Harvey, the hammock-making master mariner, worked in the shipping and passenger trades between London, Asia, and the Americas. Between 1858 and 1868, Harvey sailed on 8 voyages which lasted up to 15 months each ([n.d], i). In between periods at sea he was able to spend only “a few most delightful days” (11) with his wife, Marion, and and his children.

<21>Periods of separation from parents and siblings or wives and children could result in bouts of homesickness. Hay described the “torturing pangs of a forcible separation from the object on whom their whole affections were placed” (1953, 298). Recurrent absence also meant that sailors were removed from the rhythms and happenings of family life and unaware of even the most significant events. In 1863 Harvey learnt of the birth of his first son, Harry, when Marion came to meet him at Gravesend dock with the six month-old in her arms (41). Harvey was also unaware of Harry’s premature death in 1866, during an outbreak of cholera, until his return home. He recalled, “I came home with lots of toys I have been making for him and found that God had taken the dear little boy” (73). Harvey’s testimony demonstrates one of the strong themes in the gift-giving practices of sailors, of mediating recurrent absence with presence and presents. Harvey crafted these gifts in order to develop his relationship with his infant son during a period of leave. Perhaps Harvey expected to play with these toys alongside his son, reprising his parental role and easing his transition back into the household. Alternatively, Harvey may have made these toys to demonstrate his continuing parental responsibility and paternal love while away at sea. Sadly, the intended ameliorative emotional duties of these toys were moot and the gifts unable to develop their father-son relationship.

Gift-Giving

<22>Sailors navigated their landed relationships through gift-giving. On some occasions, gifts were exchanged before a voyage, on a sailor’s departure to sea. The exchange of engraved coins or ‘love tokens’ was a plebian practice originating in the eighteenth century, which carried on into the mid-nineteenth century. Bridget Millmore has suggested that they were gifted by sailors before departure to create a binding material link between romantic partners or family members (2015, 117). Often, however, sailors’ gifts were handmade throughout a voyage, with the intention of gifting them upon their return. These objects, intended for a wife, partner, child or family member, were often domestic in nature and included toys, teething rings, cooking utensils and knitting sheaths (West 1995, 12-16; Hansen 2015, 284). In his account of a Greenland whaling voyage in 1820, carpenter’s mate Christopher Thompson described the making of gifts from the carcasses of their catch. Thompson observed, “amongst other amusements, the sailors are…making stay bones for their "wives and sweethearts;" the whalebone they purloined from the blades that had been taken during the voyage” (1847, 152). Stay bones or stay busks are long flat pieces of whale bone or baleen, intended to be worn inside the front of a women’s stays or corsetry. Wooden stay busks were exchanged as part of courting rituals as early as the seventeenth century (Gillis 1985, 31), with sentimental connotations related to the proximity of the gift to the wearer’s heart. Later in the passage Thompson expanded upon the process of working this “whale bone”, which was likely baleen rather than actual bone, as well as one of the designs common to this form of craft. He noted, “I was often employed in what sailors dignified by the title of "bone-carving," which art consisted in cutting on the bone, with a penknife…the initials of their sweethearts” (152).

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

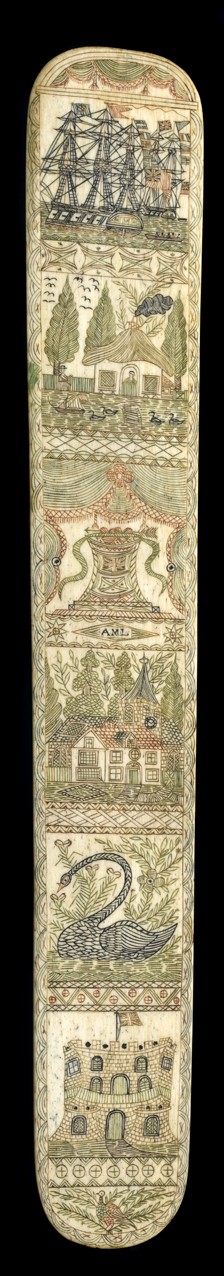

<23>A stay busk in the collections of the National Maritime Museum, crafted by an unknown engraver, shows six highly decorated panels on one side and a bloody whaling scene on the reverse (Figures 2 & 3). The six vignettes utilize a range of domestic, naval and sentimental imagery including pierced hearts, a church, a swan and a fort flying the Union Flag. The three upper sections appropriately tell the story of the connection between home and sea. The first shows two fully dressed war ships at sea, hauling up signaling flags in order to communicate with one another. The panel underneath depicts an idyllic domestic scene, in which a woman stands on the step of a thatched cottage with a smoking chimney. She looks out fondly at a man working in the yard, as a model boat floats down a stream in front. The section below this shows an altar, framed by grand theatrical curtains, upon which two hearts are struck through by the same arrow. In the center of the incised design are the letters ‘A.M.L’, suggesting that this piece was made by a sailor at sea, for his wife or partner, as described by Thompson. As a gift for ‘A.M.L’, this object connects notions of romance and domesticity with sea-faring life, drawing together the recipient at home with the sailor at sea. In addition to the intermingling of these notional spaces in the engraved designs, it is made of whalebone, bringing the products of whaling and sea labor into the home. While the stay busk was intended to be functional, the lack of wear on this object suggests it was ornamental and for display in the home when the sailor was next at sea.(2)

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

<24>Gift-giving and exchange rituals are deeply connected to the navigation of social relationships. According to Aafke Komter, they are the “symbolic nourishment which keeps interpersonal relationships alive” (1996, 3). David Cheal describes gift-giving as an “emotionally significant performance,” and an identifying factor for familial and romantic relationships. The gifted object is “a ritual offering that is a sign of involvement in and connectedness to another” (Cheal 1996, 96). Through making and giving gifts, such as stay busks, sailors acted as emotional agents, recognizing and actively working towards maintaining their significant relationships. In giving gifts which supplanted the sailor in the company of the recipient, either on the mantelpiece, in the corset or hands, sailors enabled a continued emotional and tactile presence during their absence. Maintaining this emotional presence suggests that sailors sought to ensure that they were remembered during long absences, and that the gift of their handiwork would be reciprocated.

<25>Marcel Mauss’s The Gift (1969) demonstrates that social systems and social relationships are founded on exchange. Gifts, including objects, services, labor, affection or loyalty, are given with an obligation, not just to be accepted but also returned. Mauss states to “give something is to give a part of oneself” (10) and as such “the obligation of worthy return is imperative” (41). Whilst reciprocity is a largely unspoken and unconscious element of gift-giving, sailors recognized that their craft practice has an exchange value. Alfred Spencer, the eager ropework tutee of Jimmy Pye, was once so captivated by a minister’s service that he made the minister a gift to show his gratitude. He attended the meeting in a non-conformist chapel during shore leave, while visiting the sister of his messmate in Sussex. He wrote, “I was so impressed by him and so anxious to show my appreciation in some tangible form, that I made him a piece of fancy work such as sailors do and presented it to him" (1983, 126-127). Here, Spencer used his sailors’ skill to fashion and present a gift, which rendered his appreciation tangible. The exchange value Spencer saw in his labor was implicit, to make and give a piece of craft was an act through which he was able to give thanks and build social connections.

<26>John Ford was another Naval man who used his crafting practice to develop and sustain interpersonal connections.(3) Ford joined the Royal Navy in 1838 (‘Certificate of the Service of John Ford’ 1838) and served for 24 years; building a career to become chief bosun’s mate. Being away at sea meant that Ford was away from his wife, Sarah (née Evans), and daughter, Sarah Jane, for long periods of time. He maintained his relationship with them through letter writing, gift-giving and also through needlework, as evidenced by the pin-cushion he bought for Sarah during a stopover in Lisbon (John Ford to Sarah Evans, 21 September 1846). Ford was a keen needle-crafter, who likely learnt and began his needlework practice whilst he was convalescing in 1852, after receiving a shotgun wound on HMS Janus (Crowley 2001, 65 & 73). Acquiring skills in needlework emboldened his interest in his young daughter’s education in sewing. In an 1860 letter, written to his daughter when he was stationed in Naples, he wrote “I am very Proud of Hearing of your improvement in Learning and Sewing” (John Ford to Sarah Jane Ford, 11 November 1860). Several pieces of his colored embroidery are held in the National Museum of the Royal Navy, along with his personal papers. These include two large woolwork pictures, which depict the launch of a gunship in Portsmouth Harbor (1985.762) and HMS Trafalgar at sea (2004.72). Ford also embroidered three pairs of unconstructed slipper tops (1985.353.4.1-3), which were a common domestic embroidery project in Victorian Britain (Morris 2003, 58 & 87). The slipper tops are v-shaped panels of densely-worked embroidery in a chain stitch; they remain unconstructed but would have been backed and attached to a sole. Two pairs feature pictorial toe panels with floral and color-blocked decoration on the sides. One depicts a reclining Britannia with trident in hand, and the other shows a three-masted gun ship under sail. A third pair is embroidered all over in a brightly-colored check, their smaller size suggest they may have been made as a gift for his young daughter. This suggestion is borne out by another letter, sent at Christmastime from Ford to Sarah Jane, in which he writes “I am very proud that you are such a good girl And I shall make you a nice Present when I comes home to you” (John Ford to Sarah Jane Ford, 26 December 1860). Here, Ford promised his daughter a gift in exchange for her proper behavior.

<27>On the surface, these examples demonstrate sailors exchanging their craft skill in positive ways, to express gratitude and to reward good behavior. However, these examples also indicate that the gifting of craft objects reflected the anxious nature of sailors’ relationships with land, home and their inhabitants. Furthermore, by interrogating these anxieties, the nature of reciprocated action that these sailors sought becomes apparent. Spencer describes feeling anxiety in his ability to show sufficient and appropriate gratitude to the minister. Yet, through the making and giving his piece of ‘fancy work’, he is seeking the approval and acceptance of a community as an outsider. Here, the fact that Spencer gives the gift to the minister, a pivotal member and likely gate-keeper of the community, is significant. As is the fact that he uses the craft skill he has gained from sea-faring to buy into a landed community. Ford’s promised exchange of a gift for good behavior exposes his inability to parent his child face to face. His involvement in shaping her behavior, the way she conducts herself and the person she becomes is tenuous, conducted across thousands of miles, through letters and the occasional gift. The examples of Spencer and Ford therefore demonstrate that sailors gave crafted objects as a means of stabilizing their fragile connection with families and landed communities.

<28>The anxious implications of gifting hand-made objects have been explored by Jo Turney. To craft an object for a loved one, she suggests “is to make an investment” (2015, 305) of time, labor and thought. This investment creates the emotional exchange value of the crafted object and dictates an emotional return of equal value. For Turney, a craft object is “representative of time spent touching (making), emotion, and ultimately, love, which is intended to be returned” (308). To gift a handmade object is a “binding” process; it is to “purposefully stake a claim on another and potentially manipulate affections” (307). The capacity of the gift to engender a binding connection is derived from the emotional, temporal and material potency of hand-making and the social agency of the maker. For Gell, the system of reciprocal back-and-forth inherent in gift-giving is the connective tissue with which people are connected. Gell describes gifts as “adhesive components of persons, strung between donors and recipients on loops of viscous (if imaginary) substance” (1998, 83). Gifted objects, such as stay busks, slippers and fancy work, suggest that sailors used their craft labor as a medium of emotional exchange in which their gifts were offered in return for the recipients’ continued emotional investment in the relationship. Spencer and Ford demonstrate the way in which sailors sought to underwrite their relationships using hand-made objects. In giving a piece of fancy work, Spencer fosters an adhesive bond between himself and the minister and also with the wider congregation, materializing and legitimating his connection to a landed community. Ford’s promise of a crafted reward reveals his desire to cultivate a much more long-term system of loving give-and-take with his daughter, which will continue to maintain their relationship and connectedness to one another even when he is away at sea.

Conclusion

<29>This article has demonstrated that nineteenth-century sailors actively utilized crafting processes and crafted objects to maintain and nourish their emotional connections on board and at home. The sailor-maker has been shown to have taken a proactive and deeply engaged role in the negotiation of his emotional relationships, through shared craft practice and the giving of gifts. In this way, this article adds to a growing area of scholarship which challenges traditional and middle-class conceptions of masculinity that have, as Julie Marie Strange recognizes, “excluded plebeian men as affective agents” (2012, 1009).

<30>Seamen were capable emotional navigators, realizing and expressing emotion in line with the differing systems of feeling of which they were a part. Craft was not only an appropriate form of emotional expression, but one that has been shown to have increased emotional potency, owing to its materiality and sensibility. Amongst the emotional community at sea, subject to the punitive and spatial restrictions of hierarchy, watch patterns and close quarters, men formed strong bonds with messmates. These connections were cultivated through physically and emotionally empathic shared craft practice, which strengthened friendships over long periods of time. Within relationships, the teaching of craft skills can be seen as part of the systems of give and take which underwrite interpersonal bonds. In more formal craft instruction, emotion can be seen as a learning tool, in which observation and admiration of more experienced practitioners incentivized learners to pick up skills more quickly. Craft skill in these scenarios represented legitimate seamanship and belonging.

<31>Within the emotional community of the home, from which sailors were often physically absent, craft also played a cohesive role. Periods of time spent making and thinking were fundamental in the exchange of handmade objects, wherein sailors made gifts for their children, partners or friends. These objects could provide continued emotional and physical contact, in lieu of the absent sailor. Objects and practices utilized within a domestic and familial system of feeling are markedly different from the modes of emotional communication on board ship. Within the emotional community of children, wives, parents and siblings, crafted objects function as nurturing and domestic aids, or carry the sentimental visual language of hearts, birds and cottage scenes.

<32>This study has begun to “read the silences” of these emotional communities, as Rosenwein instructs, in considering what emotional experiences are being played-down or left unsaid (2010, 17). These are particularly apposite in the emotional community of hearth and home. Landed relationships were marked by emotional separation, unfamiliarity and financial stress, but these are not mentioned in sailors’ craftwork and the written testimony surrounding it. However, these anxieties are evidenced by sailor-making. It has been suggested here that sailors used their craft practice to patch-up fractured relationships and amend inadequate parental activity, through giving gifts. Systems of reciprocity suggest that not only were sailors giving a gift, they were asking for forgiveness and continual care in return.