<1> As a scholar who specializes in the seemingly disconnected fields of Victorian literature and classical Hollywood film, I am always looking for new and different ways to solder together my two research interests in the classroom. While I do teach more traditional, adaptation-based literature and film courses on occasion, my preference is to move outside the arena of adaptation studies—to teach novels and films that speak to each other without speaking over each other, as I like to put it to my students. One course that has been particularly successful in this regard is a Literature and Gender course that I call “Women Behaving Badly: Victorian Sensation Fiction and Hollywood Film Noir.” For although they are linked by neither time nor place nor medium, sensation fiction and film noir do have a striking number of formal, thematic, and production-history attributes in common: both erupted on the popular culture scene and were produced, for the most part, over a contained period of one or two decades; both are “genre fictions” that play into audience expectations even as they work to subvert and rewrite them; both feature plots that revolve around scandalous and/or criminal acts, which must be discovered by some form of detective work; both of their narrative structures emphasize the importance of—or, rather, the inescapability of—the dark and shadowy past.

<2> But what interests me most, from a pedagogical standpoint, about the cousinly genres of sensation fiction and film noir is the way they persistently, obsessively, and viscerally dramatize the (perceived) social threat of defiant and deviant female behaviors and desires. They do this, most obviously, by providing us with some of the most infamous examples of the “femme fatale” figure in all of British literature and Hollywood film: Lucy Audley from Lady Audley’s Secret (1862), Lydia Gwilt from Armadale (1866), Phyllis Dietrichson from Double Indemnity (1944), Kathie Moffat from Out of the Past (1947), and so on. Yet the role of female transgression in both sensation fiction and film noir is, as literary and film scholars have respectively observed, a complex one; film noir’s famed cinematographic stylings notwithstanding, these are not stories that are told in black and white. Indeed, the critical tendency in recent years has been to defend and recover the genres from earlier charges of conservatism and misogyny—to show how often the genres can, in fact, be seen to complicate traditional notions of femininity and push back against the cultural construct of the femme fatale.(1) But even if we find this more progressive textual interpretation to be valid, it does not mean that the genres are any less deeply concerned with the subject of “errant” womanhood. Even if, for example, East Lynne’s Afy Hallijohn and Mildred Pierce’s titular protagonist do not turn out to be the murderous villainesses that their storylines temporarily lead us to believe them to be, they are both still clearly inscribed as “dangerously” ambitious and “problematically” un-demure.

<3> The question, though—which indeed serves as the overarching question of this course—is whether the texts under consideration seem to be advocating and reinforcing the restrictions placed on the ambit of acceptable female conduct or whether the texts’ persistent portrayal of women rebelling against such restrictions tacitly works to decry and dislodge them. It is a question that has invariably been asked by students, in one form or another, in every Victorian literature and Hollywood film course I have ever taught, and that gets at the heart of what they want to understand the most about the gender dynamics of fictional works from eras gone by. Structuring an entire course around the trope of female transgression affords me the opportunity to engage fully and directly with the branches of feminist literary theory and feminist film theory that take this question on. Or, put another way, what makes this course so compelling to my students (and, by extension, to me) is that it grows out of and perpetuates an explicitly feminist form of pedagogical practice.

<4> In pursuing a deeper understanding of 1860s fiction by refracting our analysis through the lens of 1940s film, moreover, my “Women Behaving Badly” students and I spend the semester engaging with what Megan Ward has recently dubbed “the historical middle”— the period that lies “between the Victorians and ourselves.” Ward calls for scholars of Victorian literature and culture to pay more heed to this revealing and highly relevant “historical interlocutor”; after all, as she puts it, “our present is not the only futurity that the Victorian era foreshadows” (par. 2). What this means for the Victorian studies classroom is that we need not rely solely on twenty-first-century presentism to make the resonances of nineteenth-century literary texts come to life for our students. Seeing the imprint of Victorianism on a cultural moment that both hits closer to home for them, both temporally and geographically, and still registers as a distant, alien iteration of “the past” introduces students to the methodology of comparative historicism more generally and to the comparative historicity of genre formation and appropriation in particular. As I explain in my syllabus’s course description, this is fundamentally a class about gender and genre, and about the ways in which expectations and conventions can be seen to construct and superintend them both.

<5> On the first day of the semester, I ask students which aspect of the course title made them want to join the class: was it primarily the “sensation fiction,” primarily the “film noir,” or primarily the “women behaving badly”? While some students do profess their undying love for Victorian literature or Hollywood movies, almost everyone concurs that the badly behaving women serve as the course’s main attraction. We then move into a discussion of what constitutes “bad” or “transgressive” female behavior as we know it in contemporary culture, listing all of the students’ different ideas on the board—answers range from the broad to the idiosyncratic, from the overtly criminal to the socially taboo. Next, we go through our list and check off the behaviors that are considered to be equally transgressive if performed by men. (“Murder” always gets a check mark, while “having a lot of sexual partners,” “not wanting to have any children,” and “choosing not to shave” do not.) Finally, I ask the students to think about the relationship between our list and the goals of modern feminism. Soon enough, one or more of the students hit upon the idea that feminism is, at least in part, about dismantling the gendered double standard—about giving women the right to do all the “bad” things on our list that did not get a check mark. Studying the history of female transgression is, therefore, crucial to understanding the history of feminist thought and action.

<6> At the second class meeting, we begin with a brief overview of the role that female transgression has played in the history of Western mythology. We focus predominantly on three “first-woman” myths: Eve, Pandora, and Lilith. Most of the students are quite familiar with Eve’s famous biting of the proverbial apple and Pandora’s famous opening of the proverbial box, but Lilith’s story (as told in the medieval collection of Jewish proverbs and fables, The Alphabet of Ben Sira) largely comes as a surprise. Described in this text as Adam’s true first wife, Lilith is a far more active and openly hostile character than either Eve or Pandora, fleeing from her oppressive, inequitable marriage and adamantly refusing to return, even if it means that one hundred of her offspring must die every day for the rest of eternity. I also summarize the myth of Clytemnestra—not a first-woman narrative per se, but a foundational contribution to the literary history of female transgression nonetheless. With these four mythological figures serving as our quadripartite models, we compare and contrast their various attributes, attitudes, abilities, and motivations, and conclude the day’s discussion by formulating a list of recent pop culture figures (both real and imagined) who have been accused of overstepping the bounds of social acceptability in ways that are reminiscent of either the ambitious Eve, the reckless Pandora, the mutinous Lilith, the vengeful Clytemnestra, or some combination thereof.

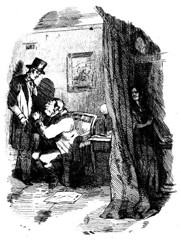

<7> These introductory discussions of female transgression are followed by two class periods devoted to introductory lectures on Victorian culture and postwar American culture, respectively, during which I detail the social, economic, and literary/cinematic conditions that helped lay the groundwork for the budding genres of sensation fiction and film noir. In order to more forcefully link these lessons to the mythology lesson that came before them, I call the students’ attention to two groundwork-laying texts in particular: W. M. Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1847-48) and G. W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929). In the former, we find a clear predecessor to the female transgressors of sensation fiction in the duplicitous anti-heroine Becky Sharp, whom Thackeray expressly associates with Clytemnestra in the novel’s most darkly suggestive illustration (Figure 1). In the latter, a work of German expressionism that anticipates film noir in its cinematography and cynicism, the title itself connects the dots between the mythological figure who unleashed all the evils of the world and the film’s iconic “vamp” protagonist who destroys those around her by unleashing her transgressive sexuality (Figure 2). Assigned readings that help inform these class discussions consist of Ann Cvetkovich’s contextualizing first chapter of Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture, and Victorian Sensationalism (“Marketing Affect: The Nineteenth-Century Sensation Novel”) and Emily Allen’s overview of “Gender and Sensation” in A Companion to Sensation Fiction on the first day, followed by Jans Wager’s similarly contextualizing chapter in Dangerous Dames: Women and Representation in the Weimar Street Film and Film Noir (“The Noir Years: U.S. War and Postwar Culture”) and Janey Place’s overview of “Women in Film Noir” in the essay collection of the same name. By configuring these two days’ discussions/readings as twinned reflections of one another, I emphasize the dialogic nature of the course and begin to mount my argument as to why sensation fiction and film noir belong in the same analytic conversation.

<9> It is an argument that has not, as far as I have found, been propounded by any other critics to date, though I do call my students’ attention to two closely related comparisons made by Julie Grossman and Guy Barefoot. In Rethinking the Femme Fatale in Film Noir: Ready for Her Close-Up, Grossman coins the term Victorinoir to demark the important connections between Victorian and noir narratives, especially when it comes to gender: “Victorian novels struggling with issues of female power can usefully be seen as precursors to film noir, which inherits yet extends Victorian narrative’s investigation of categorical representations of women as angel/whore, as ‘good girl’/‘femme fatale’” (93). Interestingly, however, Grossman makes no mention of sensation fiction at any point in her comparative analysis. Her focus is, instead, almost entirely on the late Victorian era, and on New Woman fiction in particular: “Like the cultural preoccupation with the ‘femme fatale’ figure in film noir,” she argues, “the New Woman functioned as both a symbol of female power and an opportunity for dominant cultural voices to categorize and subordinate threatening calls for female agency” (99). As compelling as I find this parallel to be, I think it makes as much or more sense to trace the Victorian ancestry of film noir back even a few decades farther to the genre that is so clearly New Woman fiction’s sociosymbolic kin.(2)

<10> Guy Barefoot, too, draws a comparison that is similar though not identical to the one that drives this class. In “East Lynne to Gas Light: Hollywood, Melodrama, and Twentieth-Century Notions of the Victorian,” Barefoot tracks the influence of Ellen Wood’s foundational sensation text upon the cluster of “gaslight melodramas” that rose to prominence in the 1940s, right alongside the rise of film noir. I make a point of acknowledging the aptness of this alternative analogy to my students; in fact, I share with them in full Tania Modleski’s early feminist critique of film scholars’ obsession with the “masculine” genre of film noir and relative dismissal of its more “feminine” gaslight counterpart:

In the forties, a new movie genre derived from Gothic novels appeared around the time that hard-boiled detective fiction was being transformed by the medium into what movie critics currently call “film noir.” Not surprisingly, film noir has received much critical scrutiny both here and abroad, while the so-called “gaslight” genre has been virtually ignored. According to many critics, film noir possesses the greatest sociological importance (in addition to its aesthetic importance) because it reveals male paranoid fears, developed during the war years, about the independence of women on the homefront. Hence the necessity in these movies of destroying or taming the aggressive, mercenary, sexually dynamic “femme fatale” whose presence is indispensable to the genre. Beginning with Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 movie version of Rebecca and continuing through and beyond George Cukor’s Gaslight in 1944, the gaslight films may be seen to reflect women’s fears about losing their unprecedented freedoms and being forced back into the homes after the men returned from fighting to take over the jobs and assume control of their families. (21)

While I can certainly see the value of teaching sensation fiction alongside the richly reminiscent genre of gaslight melodrama (and may well design such a course at some point in the future), I do think that this particular course’s thematic focus on female transgression is better served by pairing sensation fiction with film noir. Whereas gaslight films draw more from the branch of sensation fiction in which weak and/or victimized female characters predominate, noir films draw more from the branch of sensation fiction dominated by female characters who are crafty, rebellious, and headstrong.

<11> After spending the first two weeks of class carefully laying out all the various threads of my pedagogical framework, we are ready in Week Three to settle into our regularly scheduled programming of reading Victorian fiction and viewing classical Hollywood film. Since it takes much more time and effort to finish a 600-page novel than a two-hour movie, there is, admittedly, somewhat of an imbalance in the number of primary readings and viewings assigned—we generally watch ten films (spending one class period on each) and read four novels (spending three or four class periods on each, depending on the novel’s overall length). A sense of balance is achieved, however, through the course structure; throughout the semester, we methodically alternate back and forth between the genres—so that, for example, in a Monday/Wednesday class, each Monday is dedicated to discussing a section of a sensation novel, each Wednesday to discussing a noir film. What matters most, then, is that we spend an equal amount of time and energy analyzing sensation fiction and film noir. An added benefit of this structure, too, is that it requires students to read a portion of a novel, then move away from it for a while, then come back to it again—a process which mimics the fragmented, interruptive experience of reading serialized fiction.

<12> There is, of course, a wealth of primary texts for me to choose from as I craft my “Women Behaving Badly” syllabus. Though I am most fond of assigning, on the sensation front, Ellen Wood’s East Lynne (1860-61), Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret (1861-62), Wilkie Collins’s No Name (1862), and Rhoda Broughton’s Cometh Up As a Flower (1867), I also see a strong rationale for bringing in such alternate texts as Braddon’s Aurora Floyd (1863), Collins’s Armadale (1866), Broughton’s Not Wisely, but Too Well (1867), Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1871-72), or Ouida’s Moths (1880), to name some of the better known examples. In terms of film noir, my preferred lineup consists of John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941), Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944), Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945), Tay Garnett’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), Charles Vidor’s Gilda (1946), Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (1947), Orson Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai (1947), and Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950), though I can envision numerous other films working equally well—Tourneur’s Cat People (1942), Howard Hawk’s The Big Sleep (1946), John Cromwell’s Dead Reckoning (1947), Joseph H. Lewis’s Gun Crazy (1950), Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955), and so on. The key is to select a variety of texts that take on the issue of female transgression overtly but in different guises; many of the women represented in these texts are femmes fatales in a literal sense, while many others are, rather, treated as such for committing “crimes” that are far from fatal.(3)

<13> It is interesting to see how students react and respond to the motley array of transgressive female characters and transgressive female acts that these texts lay out before them. On one hand, students are accustomed to searching texts for the moral judgments that they appear to purvey—for, in other words, the texts’ assignations of heroes and villains, of right and wrong. On the other hand, however, with questions of female agency and empowerment at the forefront of our discussions all semester long, students often find themselves “liking” and “rooting for” female characters who are diegetically marked as villainesses and, in fact, feeling disappointed when seemingly brazen, defiant, and transgressive female characters are morally redeemed or converted by the story’s end. After watching, for example, a string of noir films whose concluding scenes serve either to romanticize, weaken, or vindicate the narratives’ ostensible “femme fatale” figures (Mildred Pierce, The Postman Always Rings Twice, Gilda, The Killers, and Notorious), many students find themselves delighting in the unadulterated willfulness and wickedness of Out of the Past’s Kathie Moffat; as one student put it, “I was just so happy to see a woman in one of these movies not backing down again that I didn’t really mind that the thing she wasn’t backing down from was her willingness to kill people.” Other students, meanwhile, are quick to point out the intrinsic perversity of the gendered and generic expectations that these texts construct for us: because these novels and films so persistently equate female strength with female vice, this group of students argues, we are effectively—and problematically—forced to conflate our feminist ideals with a relinquishment of basic morality. In talking through these types of issues, often quite heatedly, students begin to think more carefully about the ways in which they are affected by the various popular culture representations of gender and sexuality (not to mention race, class, ability, religion, age, and so forth) that they encounter on a daily basis.

<14> Another important dimension of the class is its integration of secondary sources to show students how contemporary scholars are able to mobilize readings of these texts for critical (and, especially, critical feminist) purposes. When I teach the class at the graduate level, I assign a diverse sampling of such criticism for the students to read in full. At the undergraduate level, though, I limit the secondary readings to what I call “provocation passages.” Provocation passages are short excerpts, usually a paragraph or two in length, from articles or book chapters that intimate the essence of the writer’s argument without going into the details that prove the argument to be true; coming up with those support details, then, becomes the job of the students. They become, in other words—and in keeping with the thematic focus of the class—“textual detectives.” Though all the students are required to read all of the different provocation passages before coming to class (ensuring they are already thinking about the issues raised by that scholar), each student is also assigned one particular provocation over the course of the semester to which he or she must respond in a two to three page paper. The student who turns in a provocation response then becomes that day’s discussion leader, having spent more time than usual pre-meditating on the provocation at hand.

<15> So, to give one example among many, on the final day of discussing No Name, I assign the following opening paragraph of Deirdre David’s “Rewriting the Male Plot in Wilkie Collins’s No Name: Captain Wragge Orders an Omelette and Mrs. Wragge Goes into Custody”:

Whether Wilkie Collins was a feminist, deployed popular literature for feminist ideology, or even liked women is not the subject of this essay. My interest is in something less explicit, perhaps not fully intentional, to be discovered in his fiction: an informing link between restlessness with dominant modes of literary form and fictional critique of dominant modes of gender politics. In what follows, I aim to show how the narrative shape of one of Collins’s most baroquely plotted, narratively complex novels is inextricably enmeshed with its thematic material. I refer to No Name, a novel whose subversion of fictional omniscience suggests Collins’s radical literary practice and whose sympathy for a rebellious heroine in search of subjectivity suggests his liberal sexual politics. To be sure, there are other Collins novels as narratively self-reflexive as No Name, The Moonstone, for one; and Man and Wife, for example, mounts a strong attack on misogynistic subjection of women (particularly when exercised by heroes of the Muscular Christian variety). But no Collins novel, in my view, so interestingly conflates resistance to dominant aesthetic and sexual ideologies as No Name, even as it ultimately displays its appropriation by the authority that both enables its existence and fuels its resistance. (186)

A passage like this serves to “provoke” students in multiple ways: even though David pointedly denies her interest in the question of authorial intent, it is a question that seems always to be lurking in students’ minds, and this provocation allows us to interrogate our own assumptions about sexual identity vs. sexual ideology more carefully. Can Collins, who is usually the only male novelist I assign all semester, really be as (or even more) sensitive to women’s issues as the women writers we have been reading? And how does our sense of gendered authorship play out in the world of film noir, where more or less all of the directors, producers, cinematographers, and editors are male yet a fair number of the screenwriters (either credited or uncredited) are female?(4) The passage, too, raises interesting questions about the relationship between a text’s thematic and formal properties and encourages students to engage in the kind of narratological reading that both sensation fiction and film noir seem be begging for, laden as they are with analepsis, prolepsis, metalepsis, voiceover narration, indirect discourse, cliffhangers, foreshadowings, dream sequences, and unreliability of various stripes. The provocation passages that we cover over the course of the semester steer students through a wide range of theoretical and methodological approaches, from the narratological to the cultural-historical, from the psychoanalytic to the postcolonial, from censorship theory to reception theory, and so forth. What all of our readings do have in common, however, is that they are all centrally concerned with issues of gender, identity, and sexuality—they all, that is, contribute to the course’s feminist pedagogical objectives.

<16> A further advantage of the cross-disciplinary nature of the course is that it allows for an interchange of critical approaches that are primarily the terrain of either Victorian studies or film studies. For instance, I introduce the students early on to Laura Mulvey’s seminal work of feminist film criticism, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which she identifies and condemns the compulsive tendency of classical Hollywood film to cast the “woman as image” and the “man as bearer of the look” (837). How, we then go on to consider, does Mulvey’s concept of the objectifying male gaze play out in the seemingly less visual medium of the novel? At which narrative moments are characters seen to be “gazing” at other characters, and what are the (sexual) power dynamics of those moments? When it comes to detective work in particular, how are vision and voyeurism tied—or not tied—to truth and knowledge? Similarly, I point out how often the Victorianist concept of the “fallen woman” is referenced and interrogated in our sensation fiction criticism, but how rarely the term is used in discussions of female transgression in film noir.(5) Does our sense of the culpability, agency, and/or subjectivity of the women of noir change when the idea of fallenness is introduced? Or does the fact that the term feels, somehow, “wrong” to apply to the later genre (as various students have contended) signal an important historical shift in the way female transgression was seen and treated in the 1940s as opposed to the 1860s?

<17> Time and again in this class, the two popular culture pasts that we are working to unearth and understand can be felt ricocheting off of one another in intriguing and instructionally productive ways. In taking students one step beyond the typical “then vs. now” dialectic of a period-based course structure (to a more “then vs. then vs. now” model), I am able to triangulate and magnify the pedagogical power of comparative analysis. And, in devoting an entire semester to the study of female transgression in fiction and film, I am able to capitalize on what Helen Hanson has recently called the “seductiveness” of such transgressivity for the feminist film (and, I would add, the feminist literary) critic: “Fatal female figures, the ways in which they are placed within genres, …and the ways in which they are part of an ongoing dialogue with popular incarnations of female identity in different contexts will continue to be a fertile area of debate. Femmes fatales always prompt questions, and for critics there’s nothing more engaging, or seductive, than that” (225). Indeed, judging from the number of students who choose to sign up for the course I have described in this essay based solely on the “badly behaving women” of its title, it is clear that it is not only professional critics who are thus engaged and seduced. Teaching Victorian sensation fiction in conjunction with Hollywood film noir is one way (among many) to harness the seductive energy of the misbehaving woman for feminist pedagogical purposes.